As part of our ten-year anniversary celebrations, we’re considering the best of a decade of arts criticism. Today’s selection comes from the editor in chief of our sister publication, Art Practical: Kara Q. Smith opines, “It’s not easy to write about three shows in 1,000 words, but what I love about this review by Matt Stromberg is his ability to nod to the [California] art history that informs these artists while synthesizing the contemporary acuteness of the projects at hand. Spend some time revisiting each one, they’ll feel as prescient as ever.” This article was originally published on December 1, 2015.

Jennifer Moon. JLS (Jennifer Laub Smasher), 2015; K’NEX, Habitrail tubes, Popsicle sticks, foam sheets, ceramic 3D print figurines, electrical wire, electrical tape, dental floss, hemp, duct tape, wood, inkjet prints, cardboard, construction paper, foamcore, fabric, folding table; 2 parts: approx. 68 ½ x 156 x 152 in.; 77 x 48 x 24 in. Courtesy of the Artist and Commonwealth & Council, Los Angeles.

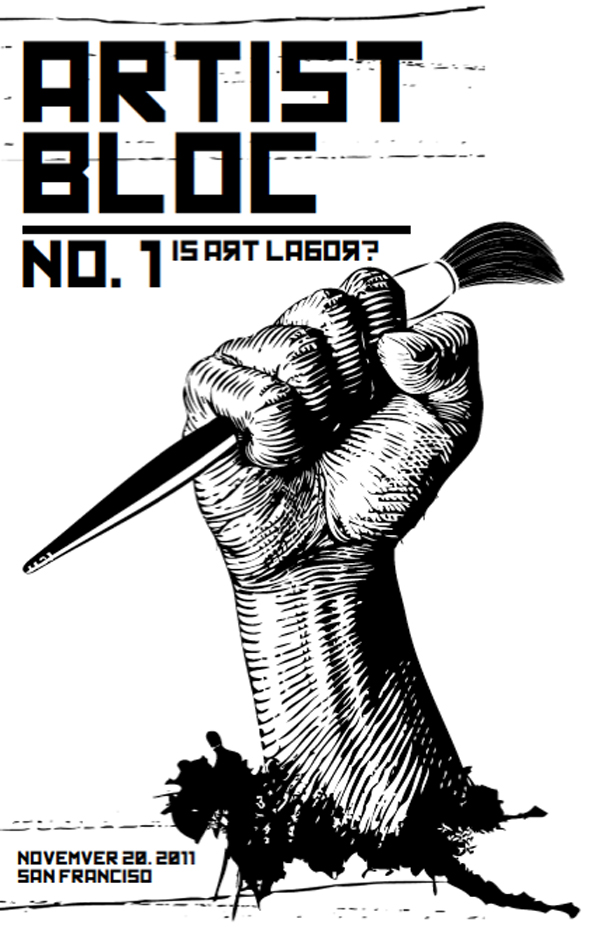

As contemporary art seems to be increasingly the province of the 1%, with continual record-breaking auctions, it may be difficult to appreciate the revolutionary origins of modernism. Early 20th-century art movements like Constructivism, Futurism, and Dada sought an aesthetic, social, and political break with the past, often with utopian goals for the future. A trio of solo shows at Commonwealth & Council aim to reinvigorate contemporary art with this revolutionary zeal.

With her Phoenix Rising series, Jennifer Moon explores the revolutionary potential of love, with ample doses of candor and humor. One particularly memorable image from Phoenix Rising, Part 2 features Moon seated in a “Black Panther”-style wicker chair, with her Pomeranian at her feet, both of them wearing matching red berets. For Moon, the personal is indeed political. A far cry from Kazimir Malevich’s severe, stark black square, Moon’s work is idiosyncratic and playful, though her aims are no less radical. Phoenix Rising, Part 3: Laub, Me, and The Revolution (The Theory of Everything) resembles a junior-high-school science fair exhibit that provides a blueprint for revolution on both a macro and micro scale. The centerpiece is JLS (Jennifer Laub Smasher) (2015), a model made of Popsicle sticks and construction toys that snakes through the gallery. It resembles a DIY version of the Large Hadron Collider, only instead of smashing protons together, it will send Moon and her partner Laub hurtling toward one another at the speed of light. Instead of the Higgs boson particle, they are searching for a new form of love free from “hierarchies, binaries, and capital,” as an explanatory panel states. 3D-printed figures of the pair stand at the entry point, ready to embark on their experiment. It is a charming and whimsical riff on quantum theory.

Read More »