Each work in Martina Sauter‘s Shapely Shadows and a New Apartment, currently on view at Ambach and Rice, is made from two images–a still image from a pixelated video or film and a real space documented with distinct clarity. The two parts are contrasting but complimentary, differing in texture and distinctness, but made to be one thing, often a fractured space or situation in flux. By setting the documented image next to the appropriated, a comparison is drawn, but there is also statement of equivalence between the two. All of Sauter’s images are made with a 35mm camera, which has the capacity to capture nearly life-like detail, coming through mainly in the documented space of her images. But film is also very good at accentuating darkness and capitalizing on extremes of light to create a nostalgic blurriness that digital photography frequently fails to capture. Through the mediation of the screen, Sauter pushes the qualities of film further into abstraction, often heavily cropping her images.

Although fragmented, the spaces are regular and the subjects seem known. Fabrics, carpet, and apolstery cover surfaces and define forms, bringing attention to their shine, plushness, or weave. Wood, brick, sheetrock and other building materials are used to give impressions of space divided or opened. Qualities of surface are vital elements in these works and seem to control the landscape. Doors are repeated throughout the works, along with frames, windows, and roofs–elements of architecture that were made to fit the human form. But the characters are often pushed to the background or set to the side throughout the exhibition–and many works don’t have any figures present at all. White walls are brought to the foreground in many of the works, seeming to echo the gallery itself, heightened by their astute framing and printing. But walls also act to conceal space, to keep some kind of truth hidden from view.

Türundlandschaft, 11.75" x 13" (Courtesy of Ambach & Rice)

In Türundlandschaft, wallpaper from the artist’s apartment becomes the vivid scenery, as seen from an interior space created by a strange heavy-handled door. The mountains look “real” and until the material’s source was revealed by the artist, I accepted this reality, even though the evergreens lacked a deep blue-green and the ground is too reddish. This color palette is reflected in the almost-black vertical stripe on the door, also capturing the blue-whites and blue-blacks of the mountains. The two panels draw us to compare these images–the landscape draws my attention through the work into the fine details, while next to it, the door brings me back to the reality that this is a constructed image.

Kacheln, 11.75" x 13" (Courtesy of Ambach & Rice)

Paired with the landscape is Kacheln, a study of yellowed tiles cropped from distant sources. The wooden seam makes an edge that should be an interior space, but appears inverted, rendering an illogical space. Here, the tiles are only differentiated by their sense of “reality”–we clearly see the streaks from hard water, but on the left, any sense of use of this space has been erased by abstraction. The effect of the color yellow varies between these two approaches—the pixelated image has a warmness to it, while the more detailed tile wall appears dingy or off-white. Kacheln and Türundlandschaft both seem to explore the psychological implications of yellow.

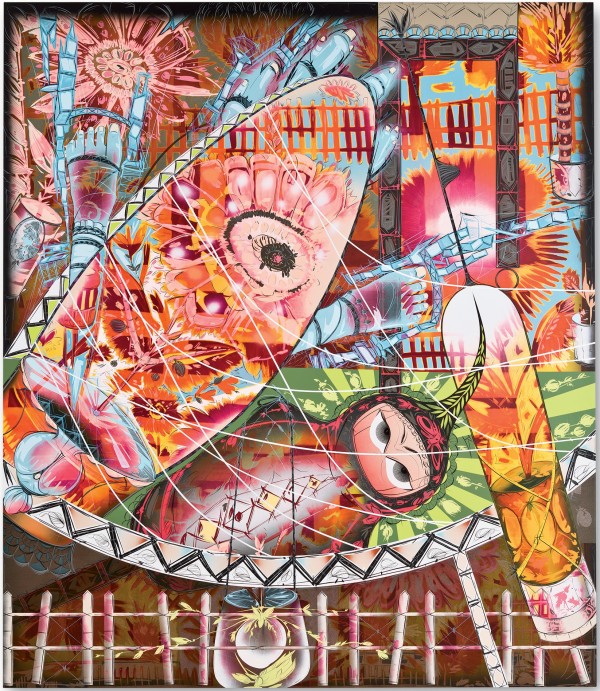

Garage, 49.25" x 39" (Installation image with audience reflections)

Like many of Sauter’s larger images, Garage is printed on reflective aluminum. As a viewer, I immediately notice my own reflection, and others too are seen as shadows on the surface of the otherwise empty space. I become a voyeur in this work, using it like a mirror to gaze at the crowd around me. It seems like we are looking into this space from from above, as though from an outside window at ground level, so there is a sense that this is a view not often seen, even more so because the space is left undecorated and unused. Because I am let loose into this open space, there is a tendency toward introspection that crops up. Having no characters in the work creates a stillness that needs no narrative. But the surfaces tell a story–the man-made materials cover the environment, eradicating all vegetation except some fall leaves that have entered, and the worn down wall itself shows the passage of time. This simple perception of the materials displayed is one reading, but there’s an essence of foreboding here in the cement and darkened roofline that’s like something we would stumble into in the films of Hitchcock.

3Stufen, 11.75" x 9.5" and Loch, 11.75" x 12.75" (Courtesy of Ambach & Rice)

Within Loch, a companion to 3Stufen, the woman’s profile is pointed toward the man’s back as he looks downward, but both are looking into a void, enveloped with shiny black hair. Both characters are isolated, but the woman’s gaze is fixed toward something or someone unseen. Characters are unaware of any spectators, so there is a sense of seeing into a private moment or possibly a mental state. But these moments are derived from very public footage and the characters could be identified if you’ve seen some films such as Contempt and Mullholland Drive.

Here is a strange, gorgeous icy woman looking very Hollywood and a man with slick hair and a flannel shirt seeming like he belongs on the streets of Seattle. Because we aren’t given a story, we draw on the little bit of context that we can forge together from the works and their position in the gallery. Film is often a passive experience for the viewer, even when there’s something to figure. out Sauter’s works don’t have to participate in the constraints that films have, but can still draw on its rich history. These works are imbued with a sense of mystery that drive the viewer’s search for clues to understand the content.

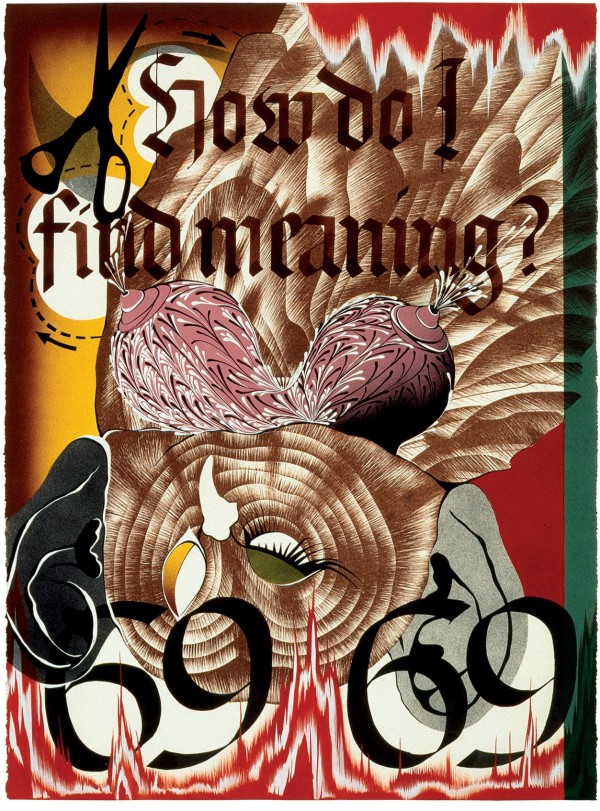

Loch & Hofmauer (Courtesy of Ambach & Rice)

Women appear prominently throughout Sauter’s compositions as glamorous forms, wrapped in towels, flowing fabrics, and styled hair, but Loch is the close-up view. She appears as if halted by wooden beams, in an unfinished house, looking into a hole, wrapped in darkness. She draws us into her single, visible eye, mimicked by the knot in the wood on the left. A hand-like form below the floating head is about to do something–and that’s a story you should tell yourself.

Sauter pursues images that she enjoys seeing, maybe looking for elegance, darkness, humor, or strangeness, in her efforts to evoke an emotion. The works seem intuitive, not meant to convey a certain meaning, but having relevance as an object of meditation for the viewer and the artist. Sometimes the works are aimed at creating suspense, but other times they appear more quotidian. Often, the imagery is drawn from the artist’s daily life, so possibly it’s saturated with the psychological associations that Sauter imagines–or maybe it’s a more simple gesture of formal exploration. The obsession with rooms or spaces and elements of architecture with little ornamentation becomes a dream-like environment that encompasses characters who have dressed themselves up for the camera.

Martina Sauter currently lives in Düsseldorf, Germany after earning a master’s degree at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf in 2006. She was awarded both the Young Artist on the Road Award by the Ludwig Forum in Aachen and the Thieme Art Award in 2006. Her work has been featured at Foam Magazine’s Fotografiemuseum Amsterdam and she’s had numerous solo and group shows since 2004, exhibiting throughout Europe and at the Aperture Gallery in New York. Her recent exhibitions include Räume auf Zeit at annex14 in Bern, Switzerland and Manuel Graf/Martina Sauter at the Kunststiftung Baden Wurttemberg in Stuttgart, Germany. Shapely Shadows and a New Apartment is on view at Ambach & Rice Gallery in Seattle, WA until October 31, 2010.