The California Biennial: So What Are We Going to Do?

L.A. Expanded: Notes from the West Coast

A weekly column by Catherine Wagley

Carlee Fernandez, "Life After Death," Taxidermy leopard, taxidermy lobster, taxidermy rabbit, pants, blouse, cape, socks, fingerless gloves, hat, sandals, bronze rifle, bronze handgun, bronze wine bottle, and wool mat, 2010. Courtesy of the artist and ACME, Los Angeles. Photo: Colin Young-Wolff

On November 2nd, 72 year-old Jerry Brown, a walking archive of California radicalism, gave his gubernatorial acceptance speech from the stage of Oakland’s Fox Theater. “Now look,” he said, with let-me-level-with-you straightness, “I like the symbolism of this theater because it was dark and . . . there were people camped in here and they were burning the ceiling and cooking their meals. But now it’s turned into a beautiful venue.” California resembled the Fox, Brown suggested: a dark, broken down shell of its former self with a charred ceiling. He ended with an even weirder sentiment:

And while I’m really into this politics thing, I still carry with me that sense of kind of missionary zeal. . . . And I’m hoping and I’m praying that this breakdown that’s gone on for so many years in the state capital . . . that the breakdown paves the way to a breakthrough. And that’s the spirit that I want to take back to Sacramento.

The spirit of hoping breakdown leads to breakthrough? It may not be exactly what he meant, but it’s what he said–it seems Brown wants to bring to Sacramento a cagier, drawn-out version of rock-bottom theory.

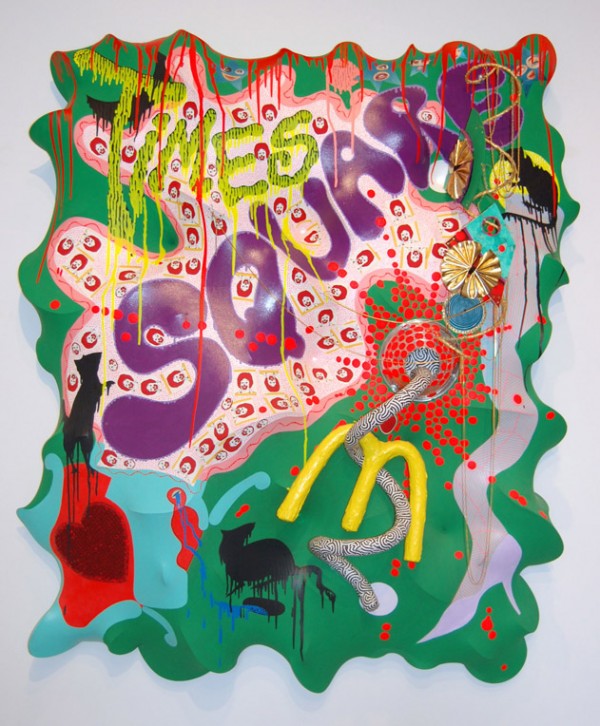

A similar spirit courses through the 2010 California Biennial, which opened at the Orange County Museum of Art (OCMA) on October 24th. The show lives in the carefully organized, carefully contextualized, and temporarily rehabilitated remnants of a breakdown, waiting patiently for breakthrough to happen.

The story of art world breakdown is old—as old as Jerry Brown—and becoming fairly tedious. It involves the gutting of expressionism, parsing of formalism, and fires burnt in what artists hoped would be the carcass of the cathedral-like modernity (which like the Fox, insists on being rehabilitated). Zlatan Vukosavljevic’s biennial contribution deals with this carcass in the glibbest way. His DuckBunny Chamber, a yellow tent shaped like the head of a flopped-over rabbit, invites viewers to enter and stand in the middle, because, as the wall label explains, so much art remains aloof and roped-off. You’re rarely allowed to look at an object from the inside. That’s been true, of course, and the perception of art as sublimely untouchable persists in many museum-goers. But, while I found standing inside the chamber whimsically pleasant, art’s austerity has been broken down so effectively (and literally, with jackhammers) that the joke feels tired. Exhausted even, not to mention uncomfortable with itself. Which is why Vukosavljevic’s glibness unnerves—DuckBunny Chamber, like much of the show, feels thoroughly comfortable with discomfort.

Vukosavljevic, born in Serbia in 1958, is one of the show’s six foreign born artists–about 20 hail from the Western U.S., 17 from the Mid-west, and 12 from the East. More interestingly, he’s also one of the oldest (only John Zurier, born in ’56, is older). The average birth year of the 45 individual artists, plus collective members, is 1973.86, and this would have been closer to 1976 if not for those few outliers who popped into the world between 1956 and 65. The show certainly has a youthfulness about it, but not a renegade energy as much as a hip, tech-savvy approach to material. It’s smart, though more bookishly informed than clever (some work–like Andy Ralph‘s spinning-wheel trash buckets–has smart-ass sass, too, thankfully). Thirty-seven artists have complete or in-progress MFAs; three have MAs, and at least three have PhDs.

But, while well-schooled, this biennial doesn’t bask in a headiness worthy of, say, Sherrie Levine or even young Dan Graham. Alex Israel’s Property offers one example of what the show does bask in. An assembly of rented props, Israel’s installation spans the length of one of OCMA’s many oddly-shaped galleries and looks like thrift-store decorating by someone with high-end ingenuity and a good design degree in his back pocket. At the center of the room, two big blue-rimmed mirrors that face each other create an endless progression of blue rectangles. The night of the opening, a man in a fedora with a well-dressed woman hovering behind him leaned in to photograph one of the mirrors, brushing his shoulder up against the other in the process. When the guard tentatively told him not to touch, the man said, ” I wouldn’t do that.” The woman clarified, “He’s an artist.” That mix of curiosity, desire and slightly inappropriate pretension seems to be what Israel’s carefully curated installation comments on, and what a few other artists dance around as well.

Stanya Kahn, "It’s Cool, I’m Good," Video, sound, 35:20 min, 2010. Courtesy of the artist and Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects.

Patrick Wilson‘s adept Albers-on-steroids acrylics; Gil Blank’s flawless, almost-commercial but anti-theatrical text paintings; and even Barry MacGregor Johnston‘s poetically un-monumental doorway installation; take a relatively risk-less approach to making. Not to say their work isn’t good. If I were their grad school professor, I’d be immensely proud: they’re knowledgeable, self-motivated thinkers who genuflect to their predecessors but in an aware, foregrounded way. They know how to wield their chosen tools, and I imagine most of them talk about their work expertly. But as an observer, someone who’s always waiting for art to show me what I don’t know, I want more.

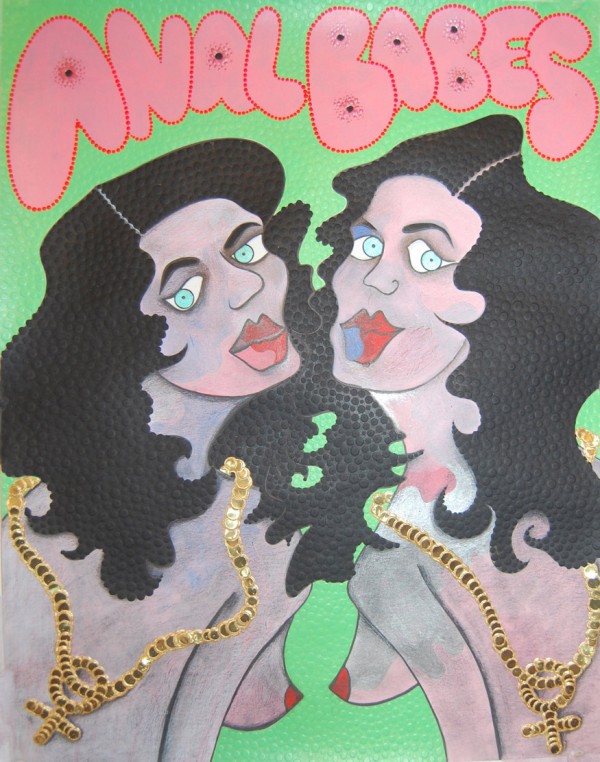

Some art gave me more of that, particularly work by the show’s women, many of whom seemed unconcerned with asserting identity, freer to indulge in the confusingness of personhood than earlier generations of feminist and female makers. Stanya Kahn’s film, It’s Cool, I’m Good, is one of my favorites. Battered and bandaged, Kahn rides and limps around the California landscape talking in a resigned, compellingly undirected manner about anything in particular: nature, food, her injuries. At one point, she sits by the ocean wearing a hospital gown and droning on about mating rituals while flies her bandages prevent her from swatting gather on her back. Yet as delightfully unconstrained as Kahn’s film feels, it still resonates with Jerry Brown’s sensibility. In it, Kahn is comfortable with brokenness, and breakthrough seems to be a mystical possibility lurking in the distance.

The same night Brown gave his Fox Theater Speech, Senator Barbara Boxer celebrated victory in Hollywood. While Brown levelheadedly assured his audience of his “missionary zeal,” Boxer unleashed zeal without warning. She hopped up and down when she said, “I am that fighter,” talked about commercials as if they were battlefronts, sucked up to Obama, made jokes about her height, and threatened to tackle “anyone who tries to hurt our state or the people in it.” She was on fire, not cagey in the least. And while Brown-like reserve has a place in politics (combativeness doesn’t always get decisions made), I want art to have more fight.

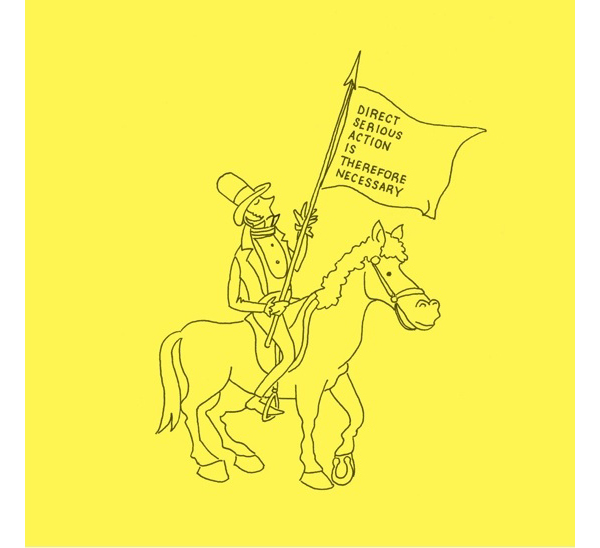

When you leave the OCMA, you see Allison Weise’s banner over the exit. In bubbly yellow text it asks, “So What Are We Going to Do?” It’s the perfect question, and the question all the work in the biennial is swimming around, whether intentionally or not. I hope the answer leads to a breakthrough with Boxer-like nerve.

Tatham (1971) and O’Sullivan (1967) met as MFA students at the

Tatham (1971) and O’Sullivan (1967) met as MFA students at the