ensaio:circuito #03, 2010

It’s a sunny day in Rio de Janeiro’s neighborhood of Lapa, a linked chain of button up shirts and people weave through the city streets. They enter into a mechanics garage and circle through the space, the mechanics continue their work; the unfolding of everyday life continues. The performative art action and the work of the mechanics rub up against each other, influencing each other without collapsing their particular flows. This is the work of Amilcar Packer, potent, yet resisting brash spectacle. Through actions, images, and videos Packer plays with the structured scaffolding of our systems of knowledge and understanding of the world. With his background in philosophy, art has become a discourse of images, sounds, and actions where the chosen medium becomes a malleable method or route for a way of thinking, a way of building and deconstructing at the same time.

Rebecca Najdowski: Bom dia Amilcar! Thanks for agreeing to have this conversation about your work. I think the first time I encountered you work was at the Centro Cultural São Paulo’s exhibition celebrating its 20 years of programming. Your works that were presented kind-of buttress your practice chronologically, but for you, your practice is less linear and more cyclical, am I right?

still #57, 2006

Amilcar Packer: The fact is that somehow the answer is no, even if the direction you took is correct… putting things in linear/cyclical is keeping the dichotomy, the split in two opposites, and even though the idea of cyclical is more correct, when talking about what we call time, it seems to me that things get a little bit more complicated. For instance, there’s a beautiful text by Walter Benjamin in which he elaborates on the idea of a constellation of historical times to criticize, or to avoid, linear time and all the entailments of cause and consequence that it establishes (of course W.B.’s ideas are much more complex than that and relate to his criticism on historiography…). One of the problems of a linear conception of time is that it often creates this idea of progress/development and when you see things in retrospective they gain this aura of necessity; that things couldn’t have happened in another way. Also, the idea of linear time brings the need of a beginning, what is pretty much connected with the monotheistic ideas of time, more specifically with Christianity. As we were talking the other day, it seems interesting to look at the idea of eternal return at a “ritual” time in which it’s not about repeating what was done in a former time, it’s rather about being there for the first time. The way I conceive it: even though everything that I do is fragmented and has different and separated pieces which appear in time, it’s about only one thing that ideally could be seen as a picture, as a non-pre-existent whole, at once and the same time, but where you can always “come back”, “return”. It gets even hard to describe using words. History is unfolding into what we call present and future, but as well as to what we call past. The past is not frozen it is constantly changing…it is always open.

RN: When you mentioned an aura of necessity, or a particular unfolding of time that is rigid – and that this is perhaps something that you avoid in your work, it makes me think in small “strategies” that you use to keep open possibilities.

AP: Those “strategies” that you’ve mentioned deal with the need to develop a practice which assumes since its “beginnings” that meaning is built and rebuilt, and most of the time, we have little control over that. It’s pretty freeing in some ways since you don’t need to elaborate strict and rigid structures to avoid noise and change, what is not programmed. Even though, of course, I have very specific directions, intentions, and wills on the context I would like my practice to participate, or ideas that I would love to take part in and which fascinate me, the beautiful thing for me is to think about how what I do is and will be seen, read and used, re-appropriated and dismantled.

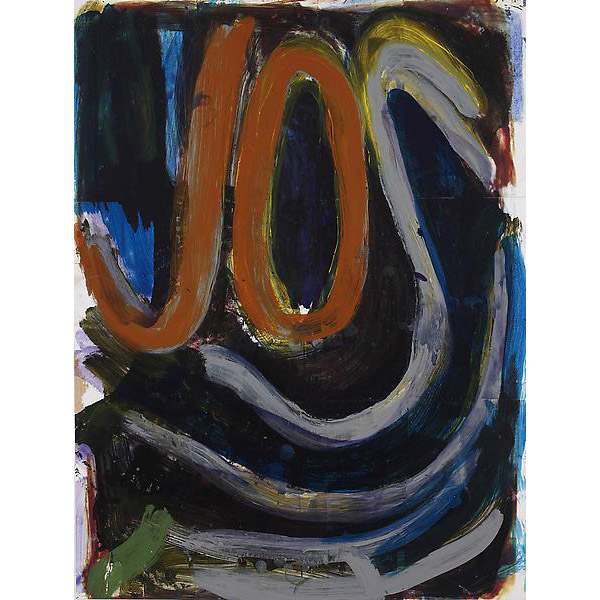

video #17, 2010

RN: I think this might be a good point to look at an image. Speaking of the “strategies”, in your Video #17 you deliberately left empty jackets. Can you speak to that a little bit?

AP: For Video #17 I had to count on the presence and collaboration of many friends, friends of friends, and some passer-byes. Even though I had an idea of the amount of jackets and individuals that I needed I knew I couldn’t fill everything because some of those places had to be left “empty” for those who couldn’t be there for various reasons. People that I would have loved to have there participating but that died before, people I would have loved to meet, people that I will meet or never will, and people that will meet the “work” after I die. The fact was/is that there must remain some empty place left. Place for possibilities or gaps, commas, intervals, silence… The action took place in downtown São Paulo and consisted of zippering together more than 100 jackets to form a circle, we turned around a building in both directions the same amount of times as if we were adulating the action, reversing it. It was not specifically about those people who were there or not, it dealt much more with ideas connected to the flow and movement of people in urban centers and how this displacement is determined by the split and organization of the “space” – all the hierarchies and world visions which determine social behavior. It is a collective body, a children’s game, but at the same time a powerful way to invoke and create energy – we can’t forget how important it is to get together in a circle with other people, and how many different human societies have used this in rituals and practices.

RN: Wow, ok… this leads me to two different (maybe not so different) wonderings:

This kind of fluid, social activity (and even the use of clothes/textile material) really seems to have some cords connecting to significant Brazilian artists like Hélio Oiticica, Lygia Pape, and Lygia Clark, but I’m curious as to how you see the relationship/s, if any.

I’m also super interested in how you use the urban landscape and all it’s implications in your work. There is so much on offer to work with. In much of your work you’ve used you own body in relation to architecture and space as a way to play with systems knowledge, to prod at them a bit. What’s happening here?

still #36, 1999

AP: I believe there are several connections in what I do with the artists you’ve mentioned. First because they certainly shaped the context in which I move and some of my world vision. They worked in a similar context as I do, Brazil and my practice have many connections with theirs: body as site, body as language, psychoanalysis, perception as subversion of the common state, revolution and freedom as for instance against morality and power, oppression and prejudices… But where I think we really do get close is in the sense that we believe that art is not an end in itself, in that maybe even “art” is not enough; or that art is always making art, that it is an action that has to create problems and formulate odd questions and become a strange body.

RN: So in the making you are sort-of proposing questions, ones that perhaps can’t be answered…I want to get back to how this is happening in the artworks themselves. Can we address that second question, about how you use the urban landscape and your own body?

AP: Concerning the urban space I guess it was discovery; a consequence that came from the experiences I’ve had in the previous works. The fact is that in the early works, the skin was a main concern as well as the clothes and the wall, but everything was taken more as surfaces – biological, cultural, architectural, social, and so on – layers and skins. I was pretty much interested in how clothes and walls function as a second skin and body and how cultural, social, and historical layers become like a second nature to us and determine social relations and world visions; they shape our behavior and our perception. But then I realized that the “skins” are thick and that it is not only about a mathematical layer… actually do you know that the skin is consider the biggest organ of the human body?!!

RN: Yes I did!

AP: Anyway, those, and some other discoveries opened up the possibility to me to work with the body in another way, to play with directions and gravity, to think about how physiological, intellectual, and “formal” structures of the human body are projected in the “outside” world and shape it symbolically and materially and solidify as rigid knowledge and power structures.

RN: So, considering this notion of “skin”, what is essentially a barrier…

AP: Something, which separates one place from another and creates hierarchies, value, segregation, split, power structures, difference. But I’m more and more interested in thinking of skins as more porous, something which defies the notions of subject, individual, particular. The skin is constantly exchanging and at the end it’s more a question of density since our bodies and minds are constantly being crossed. On another hand, other barriers try to avoid exchange and control it: country borders, jails, walls, and fences are made to avoid others to enter, to communicate. But the fact is that nothing has a unique meaning and that the scenario is further more complex and that’s why it seems much more interesting to think and to address the relations established between things as well as their contexts and not isolated objects, things, or phenomena.

RN: In some works you use barriers that are maybe less porous than skin, dense ready-mades found in the urban landscape. For instance, I really love the video installation piece where on the left side there is a panning video of glass barriers between what seems to be residential areas and public space, the right side is a video of you, or your arm, dragging a metal rod against metal fencing that seems to be in the same type of area as the other video. There is a flow that seems like this is vast space that can go on forever, this was made in São Paulo, right? Is its location important? How?

AP: The work you are mentioning is a video installation composed of two works that also function separately. Together they become “Field of dominance”. Both are ongoing videos that I have been working on for the last two years and are meant to be a collage of the same actions recorded in several cities that I visited, in video for the fences and in photographs for the glass walls. So till now you have fences from Berlin, Paris, São Paulo, Buenos Aires and so on. Each city that I’ll visit will be added to the prior video. The idea is to create an endless fence, which doesn’t consider any physical border and which in that sense refers to the idea of fence implanted in our minds. Also, the video records an action where sometimes I am inside and sometimes outside (of what is protected) which means that the landscape behind the bars sometimes is composed by houses, buildings, gardens, and other times by the street; both sides of different fences are alternated. The “glass walls”, Transparency/Opacity, is also an ongoing project which started at the end of 2009 after I realized that the walls and fences of some buildings in São Paulo were being substituted by glass and behind this fashion, that spread as a virus, I couldn’t stop seeing a perverse phenomena of transforming space into image; creating desire, fetish. As a material, the glass is considered more fancy and less aggressive than bricks and cement, or metal fences with spikes. But if one takes time to consider and reflects on the situation, it is really a complex and perverse phenomena of in-materializing the systems of power and control, of split and segregation. Formally, it’s also an endless panorama of glass walls; so far, I’ve only worked in São Paulo, but as you know, I just came back from Rio de Janeiro with a vast material to add. Actually, Rio is facing the same phenomena and as far as I know, several other cities are suffering from the same. In fact, the processes of control and surveillance, segregation and power, are global and the same strategies are being used everywhere, transnational borders…we must know that the main danger is not what we see, rather, it’s what we don’t but which is always there, a forcefield.

RN: How did you come to make the choice of placing the separate videos together?

AP: Well both seem to be part of a same urban phenomena connected with the industry of fear and the paranoia with protection and surveillance that most of the cities face nowadays. Both videos are pretty connected and form what I’ve called “field of dominance” which are relations that materialize and settle power structures, segregation, and submission and are strongly connected with ideas of private property and rights over things and space. Each video flows to a different direction – the fences from right to left and the glass walls from left to right – the videos are placed next to each other in a way to point to the space in-between them. They are developed as collages of places and cities and point of views; endless panoramic borders which place us at the center of a panopticon.

Hifen #2, 2008

RN: To take a bit of a different direction… I’m super intrigued by elements of you practice that don’t result in an “art object”. Perhaps there is a more obvious connection here to your background in philosophy, but it really seems to be important to what we were talking about before, of art (the art object) not being the end in and of itself. Your preparing for a residency in Turin, what are you going to do there.

AP: As a matter of fact, I don’t really have a formal background in visual arts, which doesn’t mean that I haven’t and don’t still study art. But as I told you the other day, for me from philosophy to art, it was just a slide. I thought I could think/do the same but in another way, for instance including the body, objects, architecture, images and sound as part of language and discourse. In recent years I’ve been asked to participate in conferences and seminars or to “present” my practice and I have been taking those opportunities to elaborate and explore another format that is a blend of talk/performance/conversation/walk and so on. A development of what I do but in a more direct way in the sense that I establish a concrete dialogue with specific persons in front of me. This has interested me for many reasons. For instance the possibility to establish a determined time/space; a situation in which the conversation and exchange is the means and the end. It is really something pretty new for me, but very exciting – a whole new field to experiment with me, for me, with other people and for other people… It doesn’t create physical objects, which I like as a principle, and it is based in conversation, which brings me back to many structures of knowledge and ways of sharing. It matters that it is art in the sense that it might help to open this kind of practice – even if there is nothing new in what I am doing and I am not looking to do something new as an avant-garde way of thinking – I intend and expect to collaborate with narration. I was recently granted to go to PAV (Parco Arte Vivente) in Turin, Italy, as part of the ResO’ residency program. The main project that I will develop there is a walking talk based in the peripatetic practice of open air lectures, with ideas connected with how historically in the western world there was/is a split between body and mind and how this shaped not only architecture, but more specifically, the formal structure of the theater spaces in stage and public, and how it came to the cinema and the art institutions, galleries, and museums. How this became the architectural and institutional frame in which the actors/artist are supposed to do something meanwhile the public observes and judges; this also connects with ideas of private property and use of the space since it seems that one of the reasons which made Aristotle walk while teaching/talking was the fact that he was not a citizen from Athens so he couldn’t posses land.

360º, 2006

RN: I think what you said about “intending to collaborate with narration” is really beautiful. If feels very in line with what I think about you work, which is making space for possibilities. Although a lot of what we have discussed is pretty heavy, I can’t just graze over the fact that a lot of your work has humor in it and knowing you as a person, you’re pretty light-hearted. Are you satisfied with the balance between sometimes-heavy subject matter and playfulness in what you output?

AP: I guess so and I think its necessary. When you talk about possibilities you open fields but nothing really assures which will become reality and I believe humor might help to deal with the unexpected. I am a big fan of irony I see it as one of the faces of intelligence (but have my doubts with cynicism and also sarcasm). For me irony makes you part of the situation, it puts you in a kind of drama or “pathos”, it creates sympathy, and makes us laugh about our own misery. For me it’s obviously a way of seeing life, a way to approach very “heavy” matters and also not to take things too personal or too serious…

RN: Yes, we all have to sometimes remind ourselves not to take things so seriously; it can often feel like a bit of a paradox….

AP: and it is… that’s exactly the point; we are the place where paradox and contradiction can co-exist.

Amilcar Packer, born in Chile, lives and works in São Paulo. His work has been extensively exhibited internationally at S.M.A.K., Ghent, Belgium, Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo, Bienal de las Américas, Museum of Art, Denver, Colorado, “2nd Thessaloniki Biennale of Contemporary Art” Thessaloniki, Greece, 2aTrienal Poligráfica de San Juan, San Juan, Porto Rico, “Third Guangzhou Triennial: Farewell to Post-Colonialism” Time Museum/Guangdong Museum of Art, Guangzhou, China, “On reason and emotion” – Biennale of Sydney 2004, Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia, National Museum of Contemporary Art, Bucharest, Romania, Ivan – Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderna, Valencia, Spain, Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation, Miami, Itaú Cultural, São Paulo, Secs Pinheiros, São Paulo, Instituto Tomie Ohtake, São Paulo, Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, among others with solo shows at Oi Futuro, Rio de Janeiro, Centro Cultural Banco do Brazil, São Paulo, Galeria Vermelho, São Paulo, Museu de Arte de Brasília, Brasília, and Centro Cultural São Paulo.