L.A. Expanded: Notes from the West Coast

A weekly column by Catherine Wagley

Elizabeth Taylor and Noel Coward, still from "Boom!," 1968, dir. Joseph Losey, screenplay by Tennessee Williams.

It makes a weird kind of sense that Elizabeth Taylor, who managed to move from sweetheart to sexpot to scandal then back to sweetheart more gracefully than any actress on record, would die the week of Tennessee Williams’ centennial. The playwright, not unlike the actress, had a remarkable knack for being glamorous and tawdry, Pulitzer-worthy and tabloid-ready at the same time. The two even followed one another’s trajectories—or, more likely, helped shape one another’s trajectories.

Williams would complete Cat on a Hot Tin Roof in 1954, debut it on Broadway in 1955 and win his second Pulitzer for it just as Taylor was preparing for Giant, her first truly memorable film as a grown-up. Then, in 1957, Taylor would sign on to star in the film version of Cat and, in ’58, snag an Academy Award nomination for her beautifully bitchy turn as Maggie. A year later, she’d receive another nomination for another Williams’ role: as the more tender Catherine who’s trying her darndest not to be lobotomized in Suddenly, Last Summer, the screen adaptation of which (Gore Vidal helped write it) cloaked all reference to homosexuality in an eerie haze.

If they flourished together, Williams and Taylor floundered together too. A decade after Suddenly, Taylor, addicted to pain killers and prone to illness, had lost five husbands and was four years into her first of two taboo-soaked marriages to Richard Burton; Williams was five years into a dark depression. The two teamed up again, but this time for a project critics savaged. In Boom!, Taylor plays an ailing husband killer who lives on her very own island, while Burton acts a stranded mystery man and Noel Coward appears as the psychic “Witch of Capri.” The footage feels like something out of a dystopian romance novel and John Waters called it “one of the most gloriously failed art films ever.” In 1989, five years after Williams’ too-early death and the same year Taylor checked out of the Betty Ford Clinic for the second time, the actress played a sinking screen siren in a made-for-TV rendition of Williams’ Sweet Bird of Youth.

“She’s the opposite of her public image,” Williams said of Taylor two years before his death. “She’s not a bitch, even though her life has been a very hell. . . . Pain and pain. She’s so delicate, fragile really.”

“I adored Tennessee,” Taylor said of Williams. “He was hopelessly naive, however.”

Justin Lowe, Untitled, 2011, collage, 10 x 8 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Pepin Moore, Los Angeles.

The Tennessee whose bust was on a chocolate cake at Skylight Books in Los Feliz last Sunday did not look naïve. He looked dapper and slyly omniscient. In celebration of what would have been the playwright’s 100th birthday, Skylight staged an afternoon of readings that ended with playwright Chris Phillips’ tribute, Garden District, set to debut at Celebration Theater in May. Like the best of devoted, obsessive fans, Phillips has trolled through Williams and unpacked the stories behind the stories, fixating on the three gay men whose deaths spur the plots of Williams’ most iconic plays: Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Suddenly, Last Summer and Streetcar Named Desire. The scene read on Sunday was between Maggie—Taylor’s role, here played by redhead Karah Donovan with an inebriating Southern drawl—and Skipper, the best friend of Maggie’s husband Brick; Maggie eggs Skipper into admitting he’s been in love with Brick.

The play, in its entirety, will likely be charming—Phillips channels Williams-esque verve with a precision that must be difficult to come by. Still, the project feels a bit like teenage love, the sort that makes you believe saying what your object of desire has left unsaid is equivalent to intimacy.

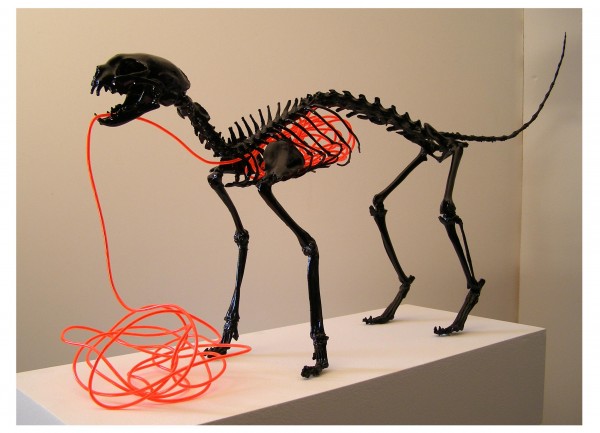

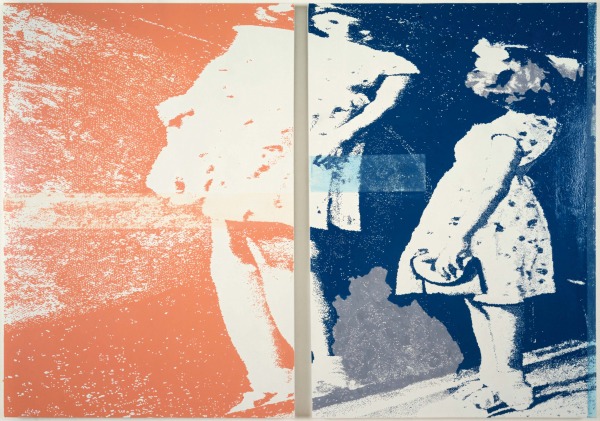

The Williams centennial reminded me of a different kind of precise and obsessive fandom: the kind at play in Justin Lowe’s frayed collages, currently on view in his exhibition Hair of the Dog at Pepin Moore. Small, smartly assembled, and all culled from trade paperbacks of the ’60s and ’70s, the collages recalls Boom! with their surreal aesthetic and borderline vulgar romanticism. Instead of unpacking and exposing, Lowe has allowed the mystery of his already-strange sources to swell. The psychedelic is compounded by the exotic, the criminal tied up with the sacred, the primitive paired with the polemical and the hopeful with the fatal, until trashy paperbacks feel as weighty and terrifying as Lord of the Flies. Reverence for the mystique of what you’ve immersed yourself in: that’s a fandom with cavernous possibilities.

Justin Lowe, Untitled, 2011, collage 5 x 11 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Pepin Moore, Los Angeles.

One of Lowe’s images strikes me as particularly inspired. It starts on the left with a dinosaur gazing at a haggard cross–a confluence of eons of real and imagined time–and ends with on the right with a man furtively disappearing into a dark city. It makes mortality feel like a slippery, sci-fi crime novel. It also reminds me of this, an experience Tennessee Williams described in the Paris Review: “I do think there was a night when I nearly died, or possibly did die. I had a strange, mystical feeling, as if I were seeing a golden light.” He added, “Elizabeth Taylor had the same experience.” It sounds as pulpy as a paperback (he saw a golden light?), but Williams, Taylor and, it seems, Lowe, all prove that pulp has an unmatchable potential for veracity.