Photographing Art in the Streets

L.A. Expanded: Notes from the West Coast

A weekly column by Catherine Wagley

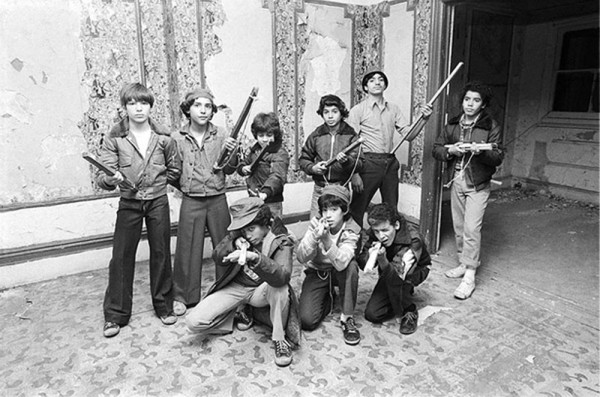

Larry Clark’s mother was an itinerant baby photographer, and she took her son with her on her rounds. This means that Clark, the photographer famous/infamous for his grittily voyeuristic depictions of youth culture, began photographing kids when he still was one. Before he reached 20, he was taking his camera deep into a late 1960s and ‘70s drug culture, documenting the experience in a way that often seemed more persuasively visceral than it probably seemed in real life. Later, he’d shadow skaters and other young creatives, obsessively immersing himself in the worlds of his subjects.

Clark is a lifestyle artist, but not of that holistic, spiritualistic or narcissistically new age “life is art and art is life” vein. He’s the kind who is just interested in doing what he wants to do and doesn’t over-fixate on boundary-crossing—or maybe fixates about boundary-crossing to the exclusion of all else.

This sensibility is what connects Clark with a good number of the street artists who share space with him in MOCA LA’s current controversial street art blockbuster, Art in the Streets. But it’s not what makes his work so well-suited to the exhibition. It’s that Clark, like most of the other photographers who appear, is really good at capturing the vibe of a given community—it’s exclusivity, its urgency, it’s quirks and attitudes.

I’m not the first to thrill over the inclusion of such a strong posse of art and journalistic photographers in Art in the Streets. It more or less pulls the exhibition out of the realm of showmanship and into a softer, smarter realm of reflection. While Banksy’s alleyways and dank walls, as dark and melodramatic as a haunted house, and Barry McGee’s five life-size sculpted taggers standing above in overturned car make it glaringly obvious that you are not in the street, but instead in a weird performance of “streetiness,” the photography pulls you back into the spaces and lifestyles this work emerged out of. Along with Clark, the show features work by photographers (and filmmakers) Martha Cooper, Henry Chalfant, Cheryl Dunn, Ed Templeton, Terry Richardson, Teen Witch and others. Each captures the sense of community and restlessness, and also the thrill of tagging and train-riding and working your way into a subculture that makes sense to you.

Henry Chalfant’s rows of tagged subways make street art look like a renegade urban beautification project, while Cooper’s wall of artists–many not included in the exhibition, some no longer living–shows the diversity and sameness of street arts participants; despite different skin color and stature, all are young and defiant and totally seductive as personas. Teen Witch’s fresher, newer images shows a coterie of friends still just as rebellious and self-contained as the groups depicted in the more historical photographs. The photography makes the show, I think. It brings the art back into the street, not literally, of course, but effectively.