Chicago

Ill Form and Void Full: New Work by Laura Letinsky at MCA Chicago

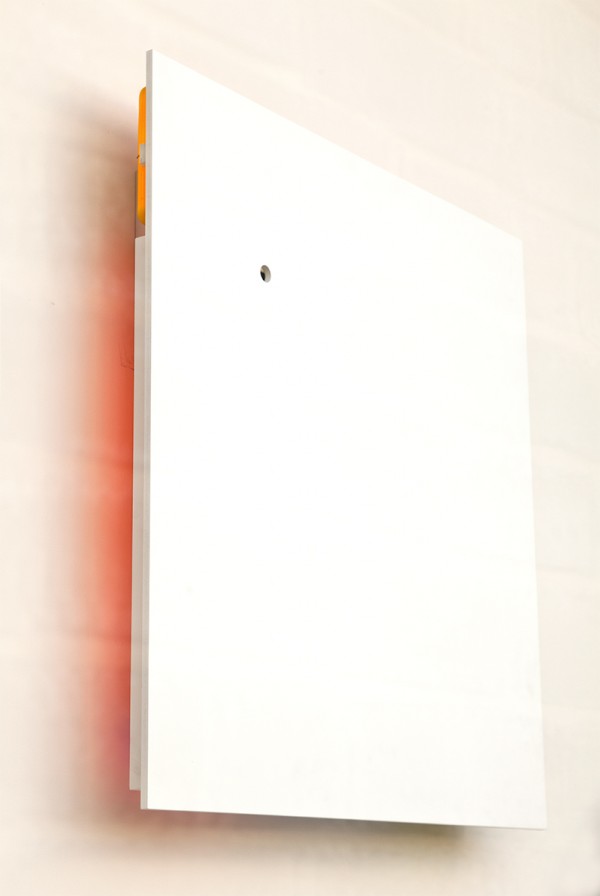

Laura Letinsky, Untitled #14 (from the Ill Form and Void Full series), 2010-2011. Courtesy of the artist; Valerie Carberry Gallery, Chicago; and Yancey Richardson Gallery, New York.

Laura Letinsky is a master at having it both ways. She photographs messes that are exquisitely tidy. She uses white like a color. She presents endings in a moment when they are still new, still vibrating with just spent energy. She captures objects as images and images as objects. She makes decay look gorgeous.

Letinsky is known for her artfully arranged still life photographs of empty ice cream bowls, half-eaten and over-ripened cantaloupes, and slumping party balloons. Over the last decade, she has chronicled the moments after the party, after the sumptuous meal, after all the ice has melted and all the guests have gone home. With the eye of a commercial art director, her photographs are as fastidiously orchestrated as those you might find in a Martha Stewart catalogue. Similar, that is, if the Grande Dame of country house finery employed petit bourgeois entertaining as a metaphor for loss, mortality, and the tragic promise of unattainable perfection, as Letinsky does.

At Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Laura Letinsky’s self-titled exhibition “Laura Letinsky” consists of large-scale still life photographs from her series Ill Form and Void Full and expands upon her exploration of earlier themes by incorporating collage elements into her tableaus. Decaying food items, wilting flowers, and dirty silverware are arranged next to magazine images of fresh fruit and sparkling serving dishes in order to create a poetic effect that complicates viewers’ perception of what is on display.

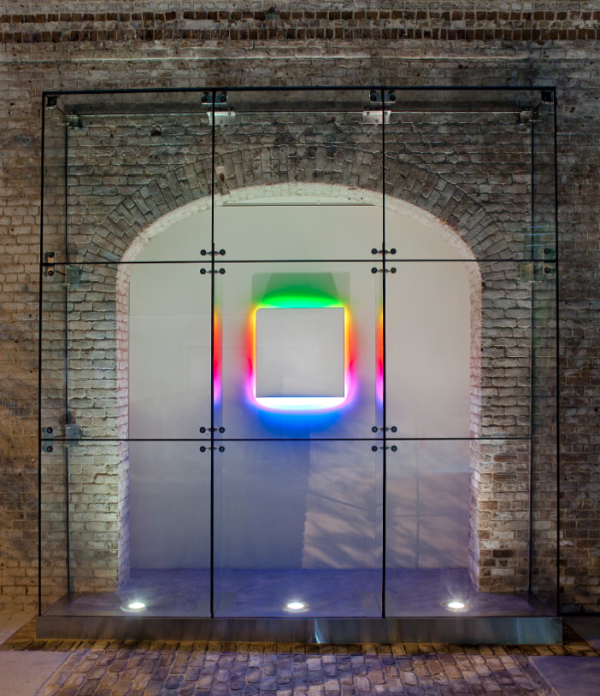

Laura Letinsky, Untitled #3 (from the series Ill Form and Void Full), 2010. Courtesy of the artist; Valerie Carberry Gallery, Chicago; and Yancey Richardson Gallery.

Within the reality of these photographs there is the constant question of which elements are authentic and which elements are mediated; what is an actual object and what is actually an image of an object? A lime rind twisting through Untitled #3 (2010) appears to be a paper cut out. But it also casts a shadow. The paper is an object in space with an image printed on it. The lime rind – as well as the ripe cantaloupe and candy dish also featured in the piece – is an idealized depiction of an every day object. It’s also an idea pertaining to decoration, one that casts a shadow on our desires as consumers and on our notions of what to strive for as members of an image conscious society, but only exists in print.