L.A. Expanded: Notes from the West Coast

A weekly column by Catherine Wagley

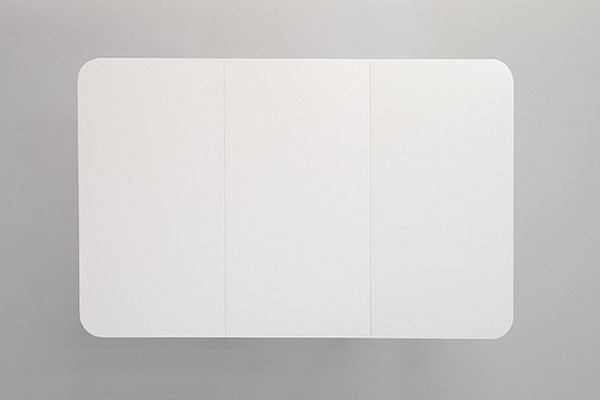

Elana Mann, "Can't Afford the Freeway."

In the only photograph I have ever seen of her, Kajon Cermak looks omniscient. She is sitting in a white sedan and glancing sideways at something worthy of a half-smile. But only a half-smile. The main traffic reporter for the public radio station KCRW, Cermak has a been-there-done-that cool to her voice which softens her otherwise feisty mien. She is very good with words: “if you’re northbound on the 405 right now, forget it,” “it’s bummer to bummer out there,” “pack-a-snack folks,” and it’s “one long, non-stop, never ending rush to stop or so it seems.” Sometimes, what she says will make me drop whatever I am doing—hopefully, I am not driving—and wonder if I’ve heard quite right. “There’s a metal bar in lanes,” she said last Tuesday afternoon, “and people are pulling up and ordering cocktails.” This made the freeway sound expensive.

It’s no small thing to be a traffic reporter in a city where a person could feasibly spend a sixth of a day on freeways (“First there was rush hour, then there were rush hours,” Cermak has said) and freeway driving has moral undertones too–a friend of mine sees glares every-time her Mercedes 240D lets out black smoke, and even if the glares aren’t actually there, the fact that she sees them says enough. L.A. artists fixate on cars, what you drive, whether you drive, and whether you should. I don’t know of another city in which art world folklore involves Robert Irwin leaving a critic on the side of the road after said critic denied the aesthetic acumen of a boy rebuilding a hot rod: “Here was a kid who wouldn’t know art from schmart, but you couldn’t talk about a more real aesthetic activity.”

The day after Cermak turned stuck-in-smog-time into cocktail-time, I took the Red Line to RedCat in downtown L.A. and sat in one of two Subaru seats set up in front of Elana Mann’s video installation. Called Can’t Afford the Freeway, after the chorus of an Aimee Mann song, Mann’s video includes abundant car time but no drive time. Mann bends across and over car seats, sometimes merging with her car’s body, and other times fighting the car’s body. The freshly washed white Subaru Legacy Outback, sits in residential streets, shopping districts and barren lots as Mann tangles herself in the seatbelts–at one point, it’s like she’s in a seatbelt straight jacket–, caresses the headrests with her cheeks or lets herself roll head-first out the window, like a pool of lotion sliding over the edge of the counter-top.

Lisa Anne Auerbach, 2009.

As Mann maneuvers, the soundtrack of her voice questioning Captain Dylan Alexander Mack, an Iraq war veteran who goes by Alex, plays out. Mann’s voice sounds polite, maybe even guarded, and Alex sounds more matter-of-fact and barefaced than he should, given what he says. At first, the interview seems like a distraction from the intensely physical dialogue Mann is having with her Outback. But then the overlaps between what Mann does and what Alex says become stronger: “Everyone was snaking and weaving” (Mann snakes and weaves around the gray upholstery), “you have resentment towards them because they’re the one’s closest to you” (Mann attacks her car sometimes, like when she throws herself on the hood), “I felt alone in the emotional attachment” (Mann is alone in every shot), “your car becomes a metaphor for your life” (for Mann, it seems to be a cocoon-like forum for acting out your feelings), “finally, I can steer my life” (Mann never steers the car), “I didn’t feel like I did anything for American culture” (Subaru may be owned by Fuji Heavy Industries, but the Outback is an American car; it doesn’t do anything in Mann’s video, though).

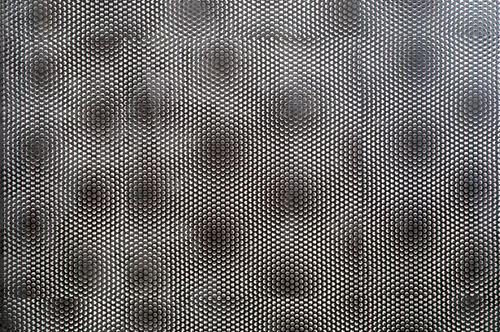

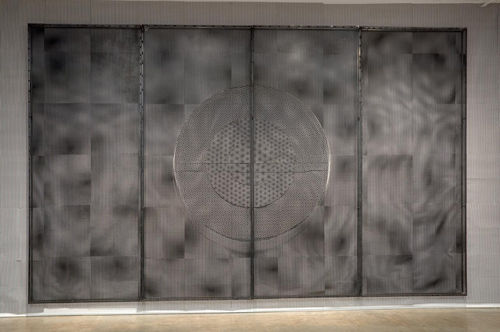

Car art has been more skin-deep than guttural lately. Artist Lisa Anne Auerbach, an adamant bicyclist, recently bought herself a car to drive to her new job in Pomona. In response to her own digression, she knitted a green sweater. On the front, above bicycles and happy hand-holding accordion people, it says, “I used to be part of the solution”; and on the back, which is bogged down by knitted cars, it says “Now I’m part of the problem.” This Spring, artists Folke Koebberling and Martin Kaltwasser began rehabilitated sedans by turning them into bikes at Bergamont Station. On designated days, visitors could come watch a process that resembled a mini demolition derby. Jedediah Caesar turned a red pick-up truck into an overgrown, inorganic ecosystem for the California Biennial last year. The pick-up felt apocalyptic.

Cars into Bicycles, 2010, Bergamont Station, Santa Monica.

Mann’s installation is too melancholic and probing to be apocalyptic. It susses out of the need for comfort and control, using the car as a proxy for trauma, war, anxiety, desire and affection. Given the emotional baggage her white Subaru carries, it’s no wonder Mann can’t afford the freeway.

Catherine Opie received her BFA from the

Catherine Opie received her BFA from the