Alex Lukas: These Are The Days of Miracle and Wonder

Alex Lukas, Untitled (010), 20inx14.75in, 2010, Ink, Acrylic, Watercolor and Gouache on Paper

Due to the ubiquity of image and video today, we have become accustomed to witnessing disasters, both man made and natural, unfold in front of our very eyes. Because of the easy access of imagery and news media, it seems as if these disasters are growing at an exponential rate and are perhaps starting to spiral out of control. The recent onslaught of crisis’, be it economical, environmental or social, has created a permeating feeling that we are now living in a highly uncertain time and the normals of stability are starting to slip away. This feeling has prompted many artists to create narratives that explore what happens when all of these disasters come together and finally threaten human life as we know it. However, it is too often that work in this vein focuses on the actual apocalyptic event, the spectacle, without much attention being placed on what happens to the world when there is only the scare of past human presence remaining.

The paintings and collages of Alex Lukas are centered on the days that take place after the “event”. The works offer a window to the future, a time that is oddly quiet, but that would look dismal to any human. In a new exhibition titled, These Are the Days of Miracle and Wonder, currently on view at the up and coming Guerrero Gallery in San Francisco, Lukas continues to explore the notion of looking to the future for information about the present, as well as documenting what it would be like to view a post-human world. The artist recently met Seth Curcio, founder and editor for DailyServing, at the gallery to discuss what events led to the moments depicted in his recent works, the time and place of these catastrophes, and what it feels like to view actual disaster images, which are currently taking place in the world.

Alex Lukas, Untitled (015), 18.875inx11in, 2010, Ink, Acrylic and Silk Screen on Book Page

Seth Curcio: The paintings that you have been creating in recent years depict a type of forgotten land that is in the process of being reclaimed by nature. Since it isn’t always clear, I’d like to get your thoughts on the possible events that led up to the quieter moments featured in your recent works?

Alex Lukas: The lack of a clear depiction of what came before is obviously very intentional. I know that the natural question raised by any depiction of “after” – which is how I think of these pieces- is “what happened?” And, that is a question that isn’t answered in the paintings. I’m interested in the idea of the confusion that will inevitably come “after” whatever has happened, be it war or disease or flooding, and how that confusion might grow with time. I imagine that the witnesses (if there are any) to the scenes depicted in these paintings might not have a clear idea of what has happened either. I think, given the breakdown of modern communications, rumors and false information will circulate and change over time – or there might be no information at all, no record of “the event” – yet it hangs over everything. I think of this sensation a little like an echo – there was a violent event, a loud clap of thunder, a tremendous bag, and in the silence afterward your ears are left ringing – even if you forget the sound, you can still hear it in the silence afterward.

Alex Lukas, Untitled (029), 2010, 42in x 90in, Ink, Acrylic, Gouache, Watercolor and Silk Screen on Paper

SC: The concepts of time and place are also interesting elements in your work. It is often difficult to discern if your scenes depict the aftermath of one catastrophic event, which is affecting several locations at once, or if we are seeing several different disasters that take place over a much longer period of time. Since time and place are so ambiguous in your work, how do you feel that you relate to these concepts and how do you feel they affect the viewer’s perception?

AL: I think of these paintings as scenes in a future – but they are depictions that reveal the past, they are focused on an after. In the paintings, this unknown “event” that I was talking about is something that has already happened, yet for us this event is still ahead – which makes for a very ambiguous time line. The locations for the drawings are created, composited or altered and generally generic, so they don’t reflect a precise place – they exist without firm landmarks that might give a clue as to where or when these places are (the tense is confusing – trying to determine where a location is from the perspective of the future looking back, but in our real time line, back is still forward). This ambiguity continues with some of the flooded cityscapes. Because I am using dated source materials, there are buildings that have now been altered or demolished or renovated, but here they stand as they were in the past, but again, they are in a future. All of this I hope leaves the viewer a little confused as to when the events happened, and it is with that sense of confusion that I hope people react to the scene.

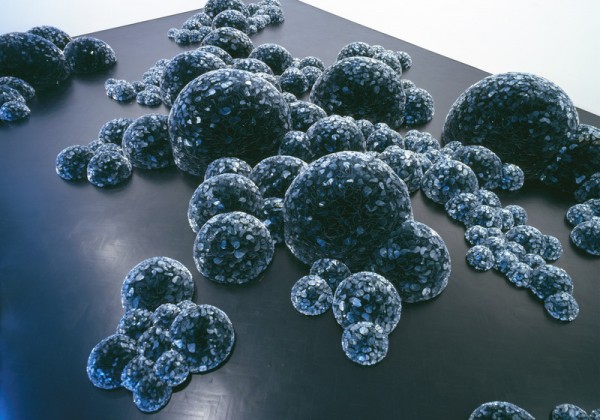

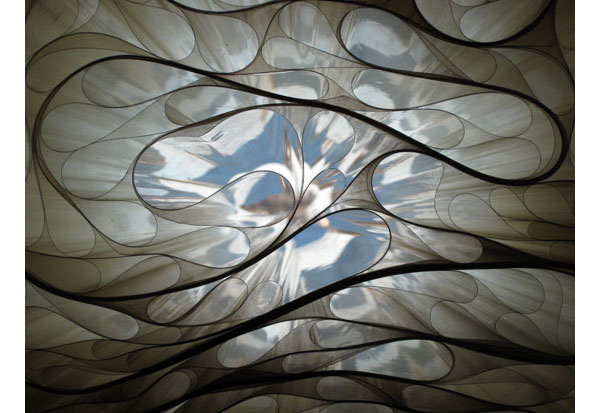

Exhibition Installation

SC: It seems that there has been exponential growth with both man made and natural disasters happening in the world recently. The ubiquity of disaster related images and videos certainly make this growth seem more apparent. How do you feel when you see actual images of disasters that threaten life as we know it, such the events of Katrina or the recent oil crisis in the Gulf? It must seem strange after working on these images in your studio all day to view images of actual events, which are strikingly similar to your paintings.

AL: I have been making these drawings since just before Katrina, and it was a very odd sensation to see images similar to what I’ve been drawing on television. Obviously it is a little unsettling, and it feels somehow wrong to draw inspiration from the suffering of others, (I’m always worried it will seem exploitative) but the political implications of these events I think are important and worth of investigation. The fact that we are seeing the second destruction of the Louisiana coast in the past five years, it speaks to the fragility of our government and the system of safety nets that we have set up for ourselves as a society. I think we have witnessed how events can easily spin out of our control – and what happens if we cannot be brought back from the brink? One of the interesting ideas that was mentioned right after Katrina, I don’t remember who said it, but you couldn’t call 911, and that is such a staple of our society, being able to get help when needed. So what happens when the police leave or are unavailable? What happens when hospitals no longer accept patients or are no longer able to treat those already in their care? (There was an amazing, heartbreaking story in the New York Times Sunday Magazine a while back by Sheri Fink about this situation during the aftermath of Katrina). This sense of isolation really interests me, the idea that there might be a day when help will not come, and then what? It all falls apart. I’m interested in exploring what specifics will bring us to this point.

These Are The Days of Miracle and Wonder will be on view at Gurerro Gallery in San Francisco until June 3rd, 2010.