All Signs Point to Yes: An Interview with Kadar Brock

When I first heard that Kadar Brock was using Dungeons and Dragons dice as engines of chance to determine the elements in his new paintings, I was as suspicious of it as I am of mullets on the L Train. I’d seen his work in several recent group shows, but it didn’t really stick with me until I saw Night Fishing at Thierry Goldberg Projects last month. Kadar’s painting was a mysterious moment in the never-ending parade of lukewarm group shows on the Lower East Side. The surface, a repeat pattern of linear diamonds, somehow felt more personal than past work I’d seen of his. It seemed that he was revealing, through reductive means, something more than an arch sense of nostalgia for a teenage fixation. Intrigued, I approached him to do this interview hoping he would shed some light on his process.

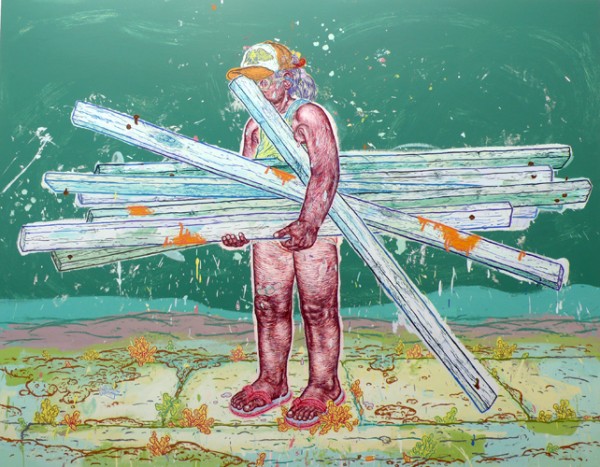

"Spell List (Resist Planar Alignment)," 2009. Marker, spray paint, and house paint on paper. 30 x 22"

Michael Tomeo: I’ve read that you use Dungeons & Dragons dice rolls to inform your compositions…how does this work?

Kadar Brock: It isn’t so much about the composition per se; it’s about determining an amount of marks. Each piece adopts a rule set from a D&D spell. These rules involve rolling a certain type of die a certain number of times, and the resultants determine how many of those zigzag marks the piece will get. That then determines the composition. But really the use of D&D is just a system or a set up. It takes away certain decisions from me and forces more onus on the mark making and paint handling to communicate things. It also sets up an analogy with abstraction – both essentially being belief systems and participatory experiences.

MT: This reminds me of how 60s artists like John Cage or Robert Rauchenberg would use the I Ching to create music or dance. I feel like the spiritual and Zen-influenced side of their work kind of got trampled by the onward march of minimalist sculpture. At the risk of sounding corny, does any spirituality from the spells influence your work? Are you into any thing like Jospeh Campell or the idea of the monomyth?

KB: Not corny at all – in fact incredibly spot on…this is what I’m getting at, while trying to co-opt/include self-criticism. It’s post-cynical romantic, i.e. incorporating and coming out on the other side of my doubts, while still maintaining and believing in this stuff I choose to call “other content” like the sublime, spiritual, romantic (essentially the lineage I find myself to be a part of). It’s about finding meaning and creating meaning. The I Ching is a set of rules too, and something that is given belief, given meaning, by the person playing by those rules or using those rules. That participation is a creative act. For me I’ve always felt that, and this really ties into Campbell, it’s my job/endeavor/whatever as an artist and human being to come up with my own sense of meaning for this life, to come up with what would be my own mode of myth. It’s the only way not to succumb to some other person’s story and the power that exerts over you, it’s also, at least for me, the only way to be sure that life is “fresh” or new to me.

I’m also very much into the spiritual connotations of spells and magic. My parents were hippies, I was raised all new age, and the reason I got into abstraction was because of its spiritual, metaphysical, and Gnostic underpinnings, and the relationship between that and my upbringing. I like the idea of abstract paintings being spells and being magical. I think using this set up, calling them spells etc. co-opts any cynicism I have about it and incorporates it, takes in my doubts and beliefs. It comes out on the other side with something.

MT: About being a post cynical romantic, correct me if I’m wrong but it seems like you are taking up where Gen X left off or maybe it’s that you don’t have to follow their well-worn paths. To generalize, Gen X seemed to know more what it didn’t want to do rather than what it did. I’m thinking of John Cusak’s famous “I don’t want to buy anything, etc…” rant from Say Anything. You don’t have Gen X’s weighty sense of nostalgia/regret and you seem to combine some ideas from the literary sense of romance, like a belief in the supernatural, but your work is also firmly placed in the unsentimental present. In other words, your work has feeling and you believe in things but you’re not like Lloyd Dobler standing with a boom box over his head in the rain, right?

KB: Yeah, I think I do believe in things. And that pretty much sums it up, I think I do… or better yet, I think about what I do believe in and challenge that, but as a means of clarifying all of it, not trying to get that nihilistic “I don’t want to do anything.” I have these moments of intensity. I have these things I relate to and feel moved by. And I see people in the past that talk about these same things, these same moments. So maybe it’s something other people relate to also. That said, maybe not everybody does, maybe some paintings ain’t gonna do shit for someone and they’ll be meaningless to them.

I think abstract painting really exists on a precipice of being meaningful and meaningless, and I really embrace that. For me the paintings are meaningful, but for someone else – nothing. Same like D&D – for someone invested in that system, someone putting into it and participating – wow! I read a study about how role-playing was able to cure someone’s social anxiety, and another one about how it cured someone’s depression. I also watched a documentary about a live action role playing community outside of Baltimore, and man, that game, that world, the characters these people played, gave their life a more pointed sense of purpose and meaning and worth. I mean, couldn’t you say by being this art maker I’m doing the same thing? I get to think and feel all these things that are incredibly important and crucial, and make all this stuff.

But yeah, for me, I am concerned with this romantic stuff. I had been taught to be cynical about it in school, to make fun of it, or use it winkingly. I’m over that though, but I also feel a responsibility to not just weep and bleed out a painting (in fact I think that’d be boring). It’s like how do I experience that moment of intensity, how do I talk about that moment with some self-awareness, that precipice of believing and feeling, while still giving into the feeling and the belief. And that in itself is another precipice between letting go (which I do in the act/action of painting), and staying self-conscious.

But to get back to your analogy, I think if I were going to be Cusak in the rain though, I’d be him in High Fidelity, figuring out relationships and feeling some shit.

"Disintegrate," 2009-10. Spray paint, house paint, and pigment dispersion on canvas (diptych). 96 x 144" (courtesy private collection)

MT: What I like is that even though you’ve poured a lot of energy into a painting, you acknowledge that someone looking at it just might not get it, and that’s ok. I don’t think you’d ever be offended by a reading of your work that might not match your intentions…

KB: Not exactly, but I’m definitely not offended if people don’t respond to it. Everyone is different, and that’s ok. Some people will get into it and others won’t and that’s fine. I do want the people into it though to get into what I’m into, and to experience that in someway. And if their interpretation is a little different, all the better, because then they’re participating more and making it more their own, which in the end, I think is more meaningful and will be more significant to them.

MT: When did you start to fully engage with myth? Did that have anything to do with a tendency toward reduction and the monochrome I’ve noticed in recent works?

KB: You know, I’m not totally sure when it started. I’ve really always been interested in that mode of thinking and relating. I mean, I’ve always thought, since like high school, that it was my job to come up with my own belief system or synthesis of belief systems in order to relate to the world in a more direct and meaningful way. I mean if you want to look at it one way, I would always draw comic book characters and fantasy characters when I was a kid – those subjects are rife with mythological content. I was reading myths in college too and making some drawings related to them – the subjects ranged from Siegfried in the Nieblungenlied to Jonathan Livingston Seagull. And I’ve always been fascinated by the myths I related to about being an artist – ideas of heroes and shamans, the magic of the painting practice and inherent communication that happens in the act of painting. The possibility to talk about things words can’t really touch on. The ability to get all this complexity of thought and feeling into on object/moment, that then can unfold and change before someone.

The shift towards monochromatic work came from wanting to challenge my belief in the myth of painting’s inherent communicative qualities and wanting to put as much pressure on my gesture/mark making as the touchstone of communicating subjective content. So yeah, it definitely relates to a myth I believe in and want to investigate, challenge, and potentially validate.

MT: Although my experience is limited, what I always liked about D&D is that despite its endless volumes of rules, the nuance of the game lies in the dungeon master’s discretionary or even improvisational application of them. Does improvisation play a role in your current work?

KB: It’s really funny, Michael, I’ve actually never played either! I wish I had, and actually would still like to now (if there’s anyone out there who’d be into it, email me). But yeah, there’s a lot of freedom in the framework – and again, it really comes down to a belief system and participating, and internalizing and making it one’s own.

In regards to the painting though, I think improvisation is everything in the work. I mean that’s where all the feeling is going to come from, all the wet “other” content. How a piece gets folded, what sort of spray/marker/house paint/other paint combination is used, how many drips, footprints, scratches, whatever, are all in the moment. The whole system thing is just that, a system, a box, a set up, so I can have as much freedom in the act of painting as possible. If I know what I’m painting, have all these limitations, the only place for the stuff I want to come through is in improvisation in the action of making it.

– Kadar Brock’s work can currently be seen in Substance Abuse, curated by Colin Heurter, at Leo Koenig Projekte, up through July 3rd, and in In.flec.tion at the Hudson Valley Center for Contemporary Art through July 26th. Conjuring and Dispelling, a solo show at Motus Fort, Tokyo, Japan, opens on June 18th.