Mella Jaarsma

Dirty Hands; Mella Jaarsma; 2010; Chains, lamps; Installation size variable; Photo: Esplanade – Theatres on the Bay

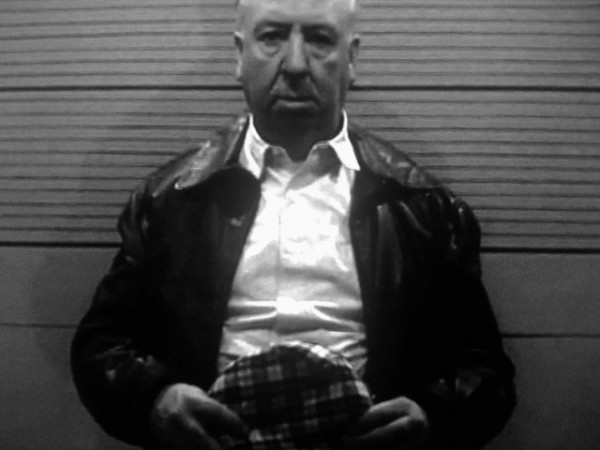

Recalling the stateliness and beauty of warriors, the delicate chainmail in Mella Jaarsma‘s latest work, Dirty Hands, is only interrupted through the visitor’s intervention in the form of light projections of 17th century Dutch prints picturing early colonial confrontations in Indonesia. While on one hand, the interactivity provides a recreation of these historical tensions, the intervention subtly implicates the viewer in their role as teller of incidents which fade into the shadows of history. Of Dutch origin, Jaarsma travelled to Jakarta, Indonesia in the early 1980s to study art, and has since been based in Yogyakarta. The use of shadows has been a fascination throughout her artistic practice, inspired by wayang (shadow puppet theatre) performances and reflections of visitors’ shadows by traditional wall lamps on roadside stalls. In Jaarsma’s body of work, one will find that her shadows have been employed as a representative of the human body and its position in relation to these cultural, social and religious surroundings.

Jaarsma’s garments also indicate our membership to specific groups by posing as a second skin. Hi Inlander is Jaarsma’s first in a series of works invoking cloaks and shelters, as symbols of human habitats in physical and cultural forms. Each garment employs a sensation of taboo, through sensitive or contentious materials to provoke dialogue and diverse interpretations of these materials across cultures. The first cloak of Hi Inlander exhibited comprised frog leg skins processed into leather and has been worn by a man at exhibitions in Indonesia, referencing the racial riots against the ethnic Chinese in Indonesia in 1998 which made apparent the fractious relations in the multi-ethnic society. The deliberate choice of frogs was used to carry across the different perceptions of animals and their roles in human culture and in this specific case, how Chinese consider frog legs a delicacy which Muslims consider unclean, yet when presented in Australia, it took on another cultural context. Jaarsma included cloaks from chicken feet, kangaroo skins and fish skins, and the wearing of the animal cloaks coincided with an event offering the meat of these four animals with a variety of spices to an international group of visitors, bringing about communal eating to open up communication and cultural insight into viewing animals and food. Chinese and French members began preparing frog legs which were eaten by other visitors for the first time and likewise, Australians did the same with kangaroo meat.

Another work based on a tumultuous historical milestone is The Follower, which was conceived of immediately after the Bali bombing in 2002 and the ensuing representation of Indonesia as a country fueling terrorism by the international media. Jaarsma carefully selected embroidered badges from a range of social organizations in Indonesia, from sports clubs, social clubs and political parties to religious communities, and sewed these emblems together – some adjacent to each other, and some on top of the other – to create a cloak which illustrates the moderate, hybrid and diverse cultural landscape of Indonesia.

Jaarsma’s work, Dirty Hands, is currently on view at The Esplanade in Singapore is a group show entitled Making History: How Southeast Asian Art Reconquers the Past to Conjure the Future. Jaarsma was born in the Netherlands in 1960, and studied visual art at Minerva Academy, Groningen, the Art Institute of Jakarta and the Indonesia Institute of the Arts. In 1988, together with her partner Nindityo Adipurnomo she founded the Cemeti Gallery in Yogyakarta (now known as Cemeti Art House) organizing exhibitions, projects and residencies. Both Jaarsma and Adipurnomo were awarded the John D. Rockefeller 3rd Prize for their significant contribution to art in Asia.