Today on DailyServing, we have gone to our wonderful friends at the Huffington Post for a brilliant article on the Baldessari retrospective, Pure Beauty, at LACMA. LA-based arts writer, Rebecca Taylor, eloquently lists some of the lessons learned from the work on view.

John Baldessari, Pure Beauty 1966-68, acrylic on canvas. Courtesy of Baldessari Studio and Glenstone

1. It’s all relative, especially Beauty

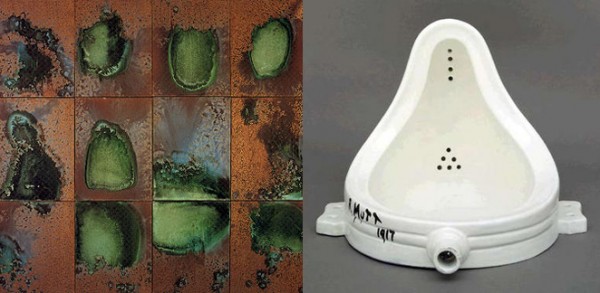

I can’t imagine a more fitting title for Baldessari’s current retrospective (on view at LACMA through 12 September 2010) than Pure Beauty. The exhibition title references an early Baldessari work of the same name from 1966-68, an off-white canvas with the phrase literally painted in black, capital letters, and was explicitly selected by the artist himself. From the dawning of Greek Classicism to well beyond the Italian Renaissance, artists learned to faithfully master contrapposto, linear perspective, and the like in order to achieve the great, mythic aspiration of beauty. Room after room in the exhibition reminds the viewer of the ubiquitous, albeit trite, truth that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. For example, in Choosing (A Game for Two Players): Carrots (1972), Baldessari asks two participants to impose their own aesthetic criteria upon a grouping of carrots (or green beans in the case of Choosing: Green Beans, 1971). As participants select the carrot that appeals most to them, said carrot is advanced to the next round and compared against two new carrots, and so on, and so forth. Ultimately this “faux exercise of taste,” as David Salle calls it, communicates the message that if there isn’t even consistency in scrutinizing a vegetable, how could we possibly impose a universal definition of beauty? Long-coveted, it continues to elude us.

2. The Rightness of Wrong

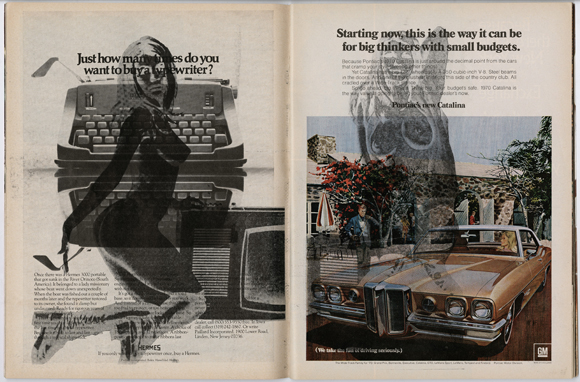

In 1996 art historian Abigail Solomon-Godeau penned the essay “The Rightness of Wrong” (1996) which praised Baldessari’s now infamous hybrid painting/photograph Wrong (1966-68) showing the artist purposefully disregarding the “rules” of photography and positioning himself in the shadow of a giant palm tree, that seems to emanate from his head, as he stands directly facing the camera in front of an ordinary tract home. Embracing “the wrong” extends well beyond this singular work and infiltrates Baldessari’s entire oeuvre, whether it’s circumventing the essence of a portrait by obliterating the face of the sitter (Portrait: Artist’s Identity Hidden with Various Hats, 1974) or using subliminal seduction – a la the panned low-art of advertising – to sell himself in his works (Embed Series: Ice Cubes: U-BUY BAL DES SSARI, 1974). Baldessari proves time and again that it’s right to be wrong.

3. Clement Greenberg doesn’t know it all

Baldessari’s Clement Greenberg (1966-68) quotes the critic’s canonical text: “ESTHETIC JUDGMENTS ARE GIVEN AND CONTAINED IN THE IMMEDIATE EXPERIENCE OF ART. THEY COINCIDE WITH IT; THEY ARE NOT ARRIVED AT AFTERWARDS THROUGH REFLECTION OR THOUGHT.” I couldn’t disagree more. What sets a work apart for me is not necessarily my initial reaction or experience – though I’m not discounting works who do pack an immediate punch, as they say – but that which infiltrates the subconscious and, in the words of Baldessari, “lingers in one’s mind.” One might liken it to the fleeting passion of puppy love, often brought on in an instant, versus the staying power of a genuine friendship, earned through time and manifestation.

John Baldessari, Heel (1986). Courtesy of Museum Associates/ LACMA

4. Banal ≠ boring

Whether arranging mundane objects in his studio according to their actual height (Alignment Series: Things in My Studio (by Height), 1975), throwing a ball in the air repeatedly to try and photograph the object in the center of the frame (Aligning: balls, 1972), methodically scribbling on a sheet of paper (I will not make any more boring art, 1971), or juxtaposing a vase of flowers with the apocalyptical text “There isn’t time” (Goya Series: There isn’t Time (1997), the ordinary becomes extraordinary when manipulated by the hands (or more accurately, the mind) of Baldessari. According to John, Sol Lewitt once told him that boredom is interesting when you work through it, and Baldessari has consistently proven this to be the case during his forty-plus year career.

5. Question what is not there with as much tenacity as you question what is there

Nam June Paik once explicated to Baldessari one of the most profound, and idiosyncratic, aspects of his work, saying that what he liked best about John’s work was what he left out. For example, in his Extended Corner series, Baldessari reproduces the exact measurements of famous canvases by Parmigianino, Bruegel, and other masters, but literally whites out the entire image, save a small rectangle in the corner. All that’s left of an epic battle scene or archetypal allegory is a small foot or corner of a building or table. Why does he negate all but the most, seemingly, trivial piece of visual information? In providing his viewer with only small, carefully selected pieces of information, Baldessari creates a conundrum for which there is no solution and allows the viewer the freedom to connect the dots and draw their own conclusions.

6. Always Rise from the Ashes

Baldessari’s work is infused with the notion that art comes out of failure and destroying things. He even describes his practice as reductive – “removing things until the work is nearly dead.” There’s no greater example than his landmark performative piece Cremation Project (1970), in which he formally ended his career as a painter. First, he gathered all the paintings he’d created prior to his photo-and-text compositions (meaning everything done before 1966) – save four he’d forgotten were in his sister’s garage -and had them cremated. In an affidavit published in the San Diego Union, Baldessari formally and publicly renounced painting in favor of a hands-off, post-studio approach. The ashes of the paintings were permanently immortalized in a book-shaped urn and a memorial plaque was commissioned declaring:

JOHN ANTHONY BALDESSARI

MAY 1953 MARCH 1966

John Baldessari (centre) overseeing Cremation Project 1970, from "Somebody to Talk To," by Jessica Morgan and John Baldessari, Tate Etc., Issue 17 / Autumn 2009.

7. Reject the stranglehold of the L.A. aesthetic, and all prevailing aesthetic authorities for that matter

The only thing consistent about Baldessari’s style is his inconsistency. He perpetually oscillates between color and black-and-white, large and small scale, text and image, etc. Beyond that, he defies simplistic categorizations. Is he a photographer or a painter? A performance or video artist? An installation or land artist? Yes, yes, and yes. Baldessari systematically rejected the pervasive L.A. style, oft called “the cool school,” and likewise rejected the philosophies of New York conceptualists Joseph Kosuth and Sol Lewitt, opting instead for his own unique visual language that defies categorization, but is irrefutably John Baldessari.

8. Viewership is active, not passive

Baldessari reminds the viewer of their importance in so many subtle ways throughout the exhibition, but most notably in A Painting That Is Its Own Documentation (1966-68), whereby the canvas is transformed into a work of art simply because it has been displayed and seen. For Baldessari, a viewer has a responsibility, not to consume images passively, but really look. In one of his iconic photo-and-text pieces, he reproduces the revered artforum (an issue with a painting by Frank Stella on the cover) and juxtaposes the magazine with a confusing edict that This is not to be looked at (1968). Baldessari, ever the contrarian, spins a tangled web with this diktat. Whether it’s a play on the meaning of image vs. object (a la Magritte), a call to “read” rather than simply look, or an autobiographical reference to his own isolation from the New York art world, the diversity of meanings and narratives derived from this “simple” juxtaposition have kept critics opining for years.

9. Irreverence is always in good order, even in regards to high art

“In the beginning, I asked myself ‘What would happen if I did this?’ and the work proceeded from there,” (Baldessari in conversation with Matthew Higgs at Frieze, 2009). This statement underscores the artist’s belief that the reason kids often make the best art is because it is made without the pretension that they’re doing “art.” Perhaps that is Baldessari’s greatest talent, humility in the face of fame and success, always making art that stems from a question rather than art for art’s sake. Indeed, Baldessari’s irreverence for the sanctity of art permeates his oeuvre, whether it be negating all but a corner of a Parmigianino masterpiece, mocking the great art critic Clement Greenberg with his own words, parodying the color-field painters by “floating” large rectangular blocks of color outside the second-story window of his home (Floating: Color, 1972), or pairing Goya’s catastrophic texts from his Disasters of War series with everyday objects like a paper clip.

10. The best way to teach art is to live art

Baldessari’s roster of former students reads like a who’s who of important artists from the past 40 years: Barbara Bloom, Liz Craft, Meg Cranston, Jack Goldstein, Karl Haendel, Skylar Haskard, Elliott Hundley, Mike Kelley, Tony Oursler, Liz Larner, Matt Mullican, Analia Saban, David Salle, and James Welling, to name a few. Stories of Baldessari’s post-studio classes, a term he first heard from Carl Andre and employed thereafter, are the stuff of legends in Los Angeles. The most often repeated description of John’s teaching style was that he treated them with respects, always thinking of them as artists, not students, and allowing them to find their own voice. Baldessari himself has said, “You can’t teach art but it might help to have really good artists around.”