Today, Daily Serving continues our seven-day summer series, Summer of Utopia, where we investigate the work of seven different artists who either employ or interrupt ideas of utopia. Full disclosure: Ted Purves was the first person I met at the California College of the Arts and—despite the fact that I don’t work in relational aesthetics—one of the reasons I decided to apply to their graduate program. He is the editor of the seminal book What We Want Is Free and founder of the country’s first MFA in Social Practice. Last week he took some time to discuss utopia, democracy, morality, and the success of the projects he creates with his partner Susanne Cockrell.

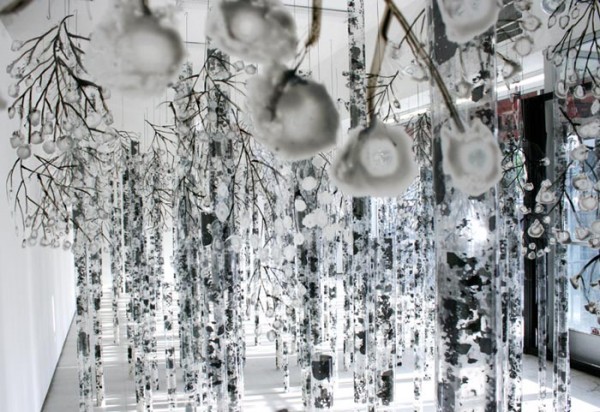

Ted Purves and Susanne Cockrell. Temescal Amity Works, July 2004-January 2007.

Bean Gilsdorf: I listened to your interview at Bad At Sports and you said, “I’m not a utopian in any way” and that intrigued me. Tell me how you’re not a utopian, working in social practice.

Ted Purves: Let’s think about what the utopian project is: generally, to design a coherent social system that satisfies all basic needs. Thomas More created this very intense class structure, and utopia saw to the needs of the upper and middle classes. It’s really horrifying, utopia, because it’s the idea of agreement about what a perfect society is. We don’t live in times of agreement or tribal identity or singular religious identity. We live in a situation of disagreement and negotiation. I’m much more interested in the notion of democracy rather than the notion of utopia, because it allows for the possibility of negotiation and change and alteration. Democracy is about the peaceful negotiation of disagreement.

BG: Has that come up in your work, like the Temescal Amity Works, that feeling of negotiating disagreement? Where has that come in for you guys?

TP: I wouldn’t say that we’ve actively looked at disagreement in our projects. We’ve been working from another starting point: the position of economies in people’s lives and how exchange functions. Even though we tend to think of ourselves as living in this highly capitalist market economy, we actually live within several different economic systems all at the same time. Getting paid and going shopping is participating in a larger capital economy, but giving a friend a lift to the store is a different, casual kind of economy. Not all of our relationships are of cliency and payment. We are interested in the way people are negotiating between competing or overlapping economies within their own lives, and creating a way to see that there are different ways to view your own personal economy. For instance, the projects about sharing fruit were about getting people to think about latent caloric energy that’s growing in the neighborhood, free of charge, at the same time that people are going out to stores to maintain their bodily lives. It’s getting people to see that we’re living in one system where we’re working to get money to buy calories when, yet, there’s another production of calories that’s going on…

BG: …aside from that, parallel with that…

Ted Purves and Susanne Cockrell. Temescal Amity Works, July 2004-January 2007.

TP: …yeah, right under our noses, that’s not being used. And how do you create a project that illuminates this other kind of economy? One project I admire is The Blue House project. It’s a really interesting counter-utopian project because it’s about creating a space for unplanning, a space for ongoing negotiation and debate in a highly planned suburb—even though the idea of that suburb wasn’t necessarily to be a utopia. I think there is a utopian interest in most kinds of civic planning because they are based on the idea that there is a perfect fix or a mostly-perfect decision to make about how you apportion resources, how you set up where people are going to live, what people need, and what’s going to make them happy.

BG: There seems to be a kind of benevolence that underlies a lot of these projects, and I wonder if you guys think about that explicitly in your work. Does morality enter into this at all?

TP: I don’t know if morality does because from our “negotiation-and-disagreement” mindset, morality is another sort of thing that is always going to be disparate among people, so it’s always going to be a negotiated space. We’re interested in working with the public and in public spaces to learn what people think and how people perceive public space around them. We start a lot of these because we don’t know everything about a situation and we’re curious about it, and we are interested in creating opportunities for research and dialogue with people.

BG: So you start with a question?

TP: Exactly. Temescal Amity Works started with questions: What is the history of the neighborhood that so many fruit trees were planted here? How do we negotiate the idea of the developed economy of the neighborhood? And that’s given way to a larger set of questions that we’re thinking about: how does the social imagination continue to drive people’s decisions, beliefs, lifestyle choices? What kinds of social imaginaries regarding the rural inhabit the minds of people in cities?

Ted Purves and Susanne Cockrell. Lemon Everlasting Backyard Battery, 2008; installation view at San Jose Institute for Contemporary Art.

BG: When do you feel a project is successful? What makes you go home and high-five each other at the end of the day?

TP: I feel like a project is successful if we have had substantive encounters with people, if we have created spaces where a kind of exchange—whether it’s family history, or talking about why something should or shouldn’t be in an art museum, or sometimes it’s just swapping recipes—some form of animated or engaged dialogue comes out, or some sort of story emerges. It means we learn something, a story can be brought forward from that, that’s when things are successful. Another high-five moment comes when there is something compelling to look at. A lot of times when you see a social practice show, it’s either a room full of crap to read, or it looks like a place where they had a party and you didn’t get to go. I’ve been to a lot of those, and they’re not satisfying! You either wish they had just printed a book you could take home and read in your own chair—because it’s not very comfortable to sit in a museum—or you wish that you’d been at the party. When we did Lemon Everlasting Backyard Battery we had hundreds of jars of lemons on this table, and it was beautiful.

BG: It sounds like bringing aesthetics back into it is important.

TP: Yes, certainly when there’s a material expectation for it to be art. [Lemon Everlasting] was great for us, because it got to be beautiful-looking, but it also got to do something; two things were happening in the same space. It occupied the institution and it challenged the institution in ways that were playful, functional and aesthetically critical. Aesthetics are important. Obviously some artists don’t think this way. They can just go in and do straight up exercises, and by the rules of the game that’s art too, but for us there’s got to be something else, a twist, a different way of seeing. We’re working in public space, so we need to challenge public expectations, a kind of weirdness, wrongness, whatever that might be.

BG: Do you think of projects as iterative? Would you want to restage that project, or do something similar someplace else? Or have the questions been answered and now you can move on to other questions that have been formed by the outcome?

TP: That’s a great question. I think it depends from project to project. I would definitely say that you never answer all the questions. The new thing we’ve been working on is this ongoing newspaper project, The Meadow Network. We structured it in a specific way because a thing like Temescal Amity Works was such a Herculean effort that you don’t want to do it again! We created TMN so that there was an option to have a repeatable form that could grow on itself, so that we wouldn’t have to reinvent an entire project every single time… That only half answers the question: I think it is good to have some projects or programs that are sort of open-ended but able to be temporarily concluded, because some questions don’t go away.