Interview with Babak Golkar

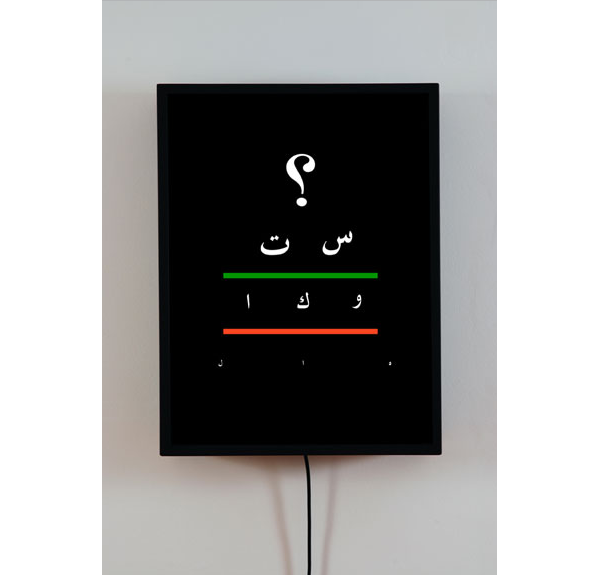

Babak Golkar is a multi-disciplinary artist whose practice, at its fundamental roots, takes aim to deconstruct, recontextualize and rearrange our perceptions of the world around us. Like Zen koans, Golkar’s work seems to arrive at new understandings by setting up impossible questions. At it’s core is a spirit of unbridled philosophical investigation; one that exhibits a Duchampian twist on the visual pun mixed with a Gestalt sense of multistability and reification. Golkar’s work understands both the destructive and regenerative aspects of perspective and shifting visions; and fundamentally contests the fixity of subject and object and space. And, like his work, Golkar’s visual language maneuvers between seemingly oppositional realms–East and West, politics and revolution, Modernity and antiquity, Minimalism and ornament—ultimately exposing not the dialectical relationship between polarities, but rather the poeticism in the world around us.

Sasha M. Lee: I wanted to begin with your series “Negotiating Space,” in which you use Nomadic Persian Carpets as a kind of architectural support, transforming its geometric twists and turns into rough blueprints for gleaming, white, three-dimensional models, rising from the woven geometric patterns. I thought the title and the conceptual framework of the work, for me, was actually a poetic way to summarize many of the themes that run through your work. Can you talk about how these forms interact, and why you chose to juxtapose these particular forms in this manner?

Babak Golkar: I’m interested in the alchemy of the art practice…arriving at gold, metaphorically of course, some sort of proposal for new understandings, the creation of new meaning. I like the idea of a particular piece transforming from two dimensions to three dimensions; something non-existent becoming a possible structure, and the subsequent interaction between the two. I like to talk about my work in terms of “becoming,” of interdependency between these two forms. In the case of the series “Negotiating Space” I don’t like to look at the nomadic Persian carpet as the origin of the whole thing per say…but rather one visual form constantly becoming the other and vise versa.

Hence the title—I like to use titles as materials in and of themselves– it is carefully chosen to hint at a state of uncertainty, a fluid or malleable state of existence. Really, I call the works “proposals,” rather than installations or sculptures.

Even though the carpet is technically the blueprint for the architectural scale-models, the structure adds a vertical dimension, which, as you move above the piece it collapses back to carpet once again. I like to talk about this idea of 2D to 3D, and its reversal; in particular the Duchampian aspect of playing with space. I’m inspired by Duchamp’s alchemical approaches to art making. In some ways I make a reference to Duchamp, in particular his piece, 3 Standard Stoppages. Do you know that piece?