Tell Him He’s Perfect

L.A. Expanded: Notes from the West Coast

A weekly column by Catherine Wagley

Rise of Rebellion: DailyServing’s latest week-long series

We continue our week long series, Rise of Rebellion, by taking a look at how resistance and rebellion overlap.

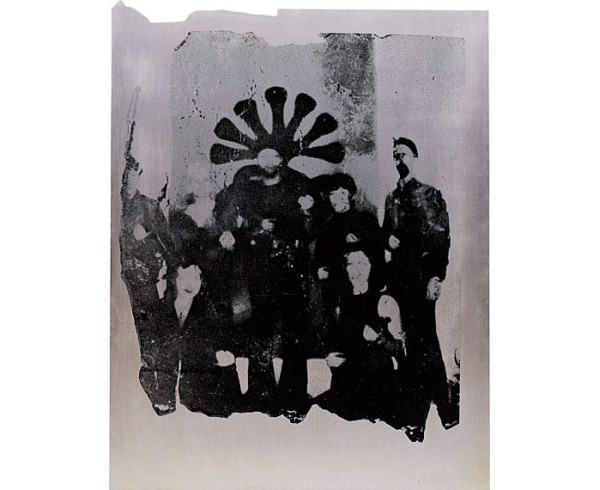

On the back left wall of Pepin Moore‘s gallery space–the same endearingly domestic space that, just a few months ago, belonged to China Art Objects–there’s a noirish print by Brian Bress. It’s hanging in Second Story, a low-key exhibition that features a sampling of the artist’s multiples that will be shown in the upstairs loft once the gallery’s official season begins. It depicts a bust that, I think, once belonged to Natalie Wood. But the face has been obscured by torn strips of paper and it’s the obscuring that matters most. The print recalls Irving Penn’s Saul Steinberg in Nose Mask (1966) or Marcello Nizzoli’s Portrait of a Woman (1936), a photograph in which a smiling female face is half covered by white paper and colored with green and red crayon. It resists beauty, but it’s still elegant.

This particular print feels like a distilled version of Bress’s more unruly installation and video work, and the crinkles in the brownish and purple paper that cover the face particularly resonate with the surfaces of Disaster Family, a limbless fantasia of felt figures that Bress included in LACE’s 2008 exhibition, Against the Grain. There’s something violent about Bress’s refusal to give figures flesh or features–it obscures individuality while internalizing intimacy and resisting the outside world.

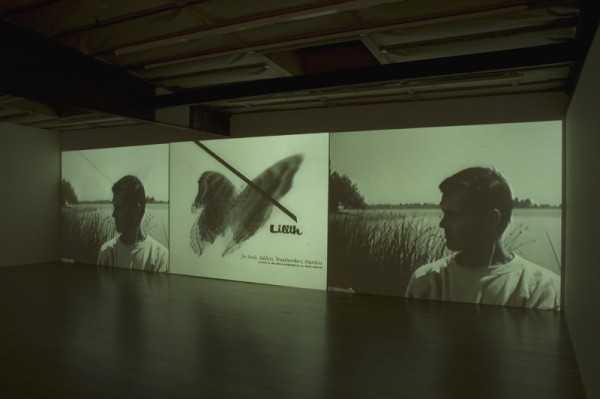

Resistance was more or less the point of Against the Grain; it aimed to subvert a stiff political aesthetic in favor of something more sensuously contentious. It responded to Against Nature, a 1988 exhibition curated by Dennis Cooper and Richard Hawkins, and both shows took their titles from different translations of A Rebours, a melancholic French novel by J.K. Huysmans about a sickly nobleman who withdraws from society to live alone with his own exquisite sense of decorum. But only a few pieces in Against the Grain–Bress’s was one, along with Julian Hoeber‘s series of glitzy bronze heads–came close to the seductive recalcitrance of Against Nature, which confronted the problem AIDS posed for artists who wanted to be provocative without being polemical.

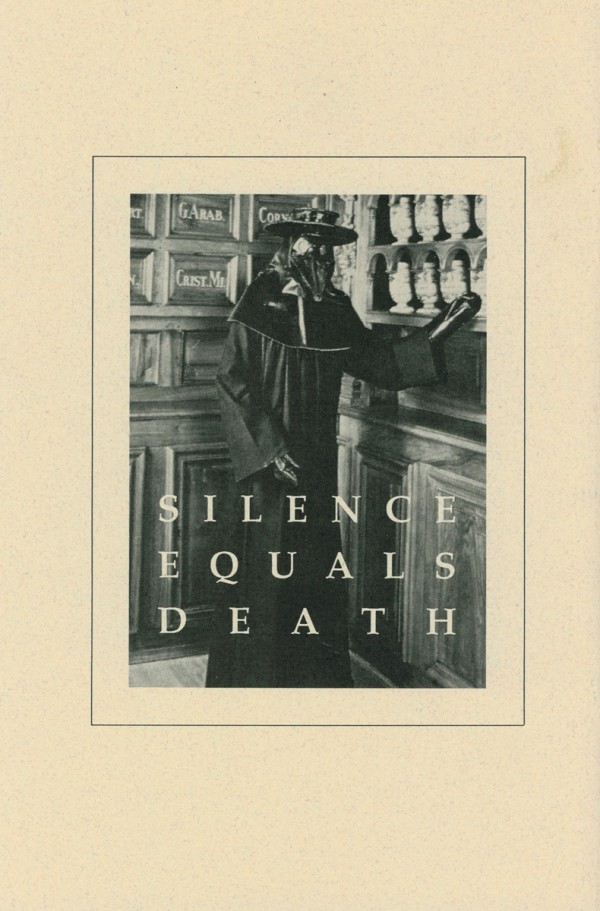

By 1988, the clean-edged, unambiguous Silence=Death icon, designed by AIDS activists in New York, was already circulating. The back cover of Against Nature‘s catalog echoed the slogan but did so by superimposing a seraph script over an image of an apothecary dressed in a black-beaked, plague-resistant gown (he could have easily figured into Bress’s Disaster Family). Against Nature didn’t reject the political dimensions of sickness in general or AIDS in particular, but it did favor ornamental musings on beauty, bodies and illness and its fidelity to taste seemed strangely aggressive.

In his catalog essay for Against Nature, which reads like fiction, Dennis Cooper navigates his desire for a man named Pierre, who is purportedly trying to help Cooper out by writing about the exhibition. The two men move back and forth in cagey, often tangential dialogue. In the end, Pierre makes it clear that he’d rather not get too close to Cooper; it’s not because he’s afraid of AIDS but more because he just doesn’t know what to be afraid of or what to want in general. When Cooper reads what Pierre has written, he realizes it’s unusable:

(It’s a description of Pierre in very hackneyed, glowing terms . . . it doesn’t have anything to do with this show, [and there’s no way I’m going to print it] as beautiful as Pierre looks today, even upset. But he’s my friend so I’ll tell him he’s perfect.)

The essay, like Pierre, is evasive and uncertain. It resists pontification, though written in a moment that seemed (and was) politically dire, and it resists indulgently.

Indulging in ambiguity can be dangerous–you risk being misunderstood–but it’s indulgence that made Against Nature so timely and rebellious.