Caught in the Act

L.A. Expanded: Notes from the West Coast

A weekly column by Catherine Wagley

In 1975, when Bob Dylan was on his Rolling Thunder Revue tour, traveling the country with an entourage of creatives—among them Joni Mitchell, Allen Ginsberg, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, and Joan Baez—he played Madison Square Gardens. As had become his habit, he wore black-eyeliner over whiteface makeup and a feathered, flat-brimmed hat on top of unruly curls. He didn’t look like Dylan, though he didn’t look like anyone else either.

Mid-set, Joan Baez dashed out onto the stage dressed exactly like him, eyeliner and all. According to playwright Sam Shephard, the two were briefly indistinguishable. “There’s so many mixtures of imagery coming out,” wrote Shephard in retrospect, “like French clowns, like medicine show, like minstrels, like voodoo, that your eyes stay completely hooked and you almost forget the music.” And it wasn’t just that you almost forgot the music. It’s that forgetting became essential to staying “hooked.” Until you heard their familiar voices, they almost were clownish medicine-man-minstrels. But when their mouths opened, Baez became Baez and Dylan became Dylan just playing an elaborate game of dress up.

The best distillations of the Rolling Thunder days tend to be still images. One in particular gets at the strange mix of masking, self-control, and chasmal vulnerability that characterized that tour. In it, Dylan, in makeup and hat, has his hands out in what could be either a “here-I-am” or “stop-right-there” gesture. It’s like he’s cagily reinvented Baptiste Debureau as a pre-punk pantomime who’s petrified of losing his audience but determined to keep them at arm’s length. The image forever freezes him in that vaguely forceful, half-welcoming, half-shunning pose.

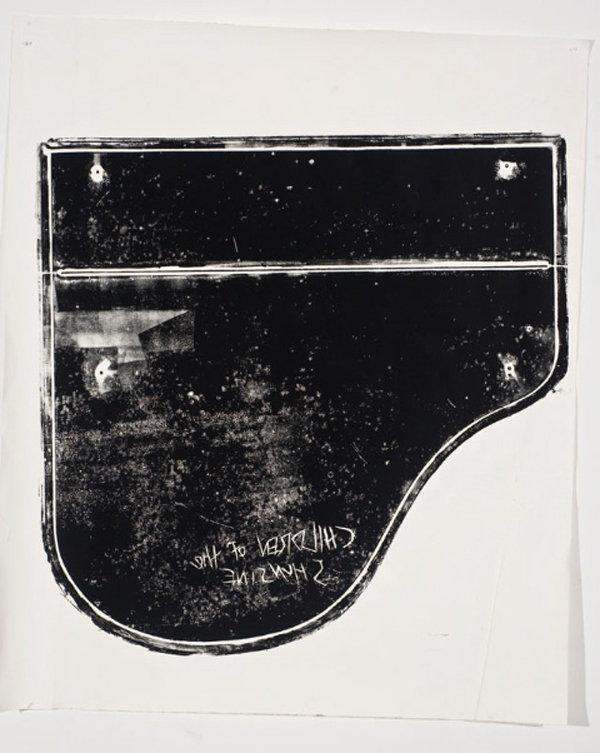

David Noonan’s silkscreen prints have a similar vague forcefulness. Noonan’s current exhibition at David Kordansky Gallery includes nine large black and white prints on roughly layered linen, all of which document theatrical moments. These are found images, blown up and superimposed on other found images. In most, characters are masked or painted up like mimes; some are caught mid-action, while others seem to be waiting to act or collecting themselves after acting. In one image, a youngish boy stands in an undershirt, jock strap, and full makeup. The guarded smirk on his face, accentuated by heavy eyeliner, makes him look like he knows more than he understands. Another character, as androgynously full-bodied as Antony Hegarty in Epilepsy is Dancing,wears a long white tunic and hunches over. His floral necklaces fall forward and he’s sort of lost in himself, but purposefully so—it’s a performer’s job is to get lost like that. A third with Marlene Dietrich eyes leans over two small, doll-like bodies, playing puppet master. Together, the images in the room become a troupe that’s part punk, part Rive Gauche, part gypsy, part Hollywood.

David Noonan, "Untitled (Orlando)," screenprint on linen mounted on plywood, powder coated steel, 2010. Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles, CA.

But the most resonant character in the exhibition isn’t necessarily part of the troupe at all. He’s all but alone in a side room adjacent to the gallery’s office, and titled Orlando, which is the name of Virginia Woolf’s notorious man-to-woman protagonist and sounds a lot like “Renaldo,” the name of Dylan’s alter ego during Rolling Thunder days. A three dimensional plywood cut-out covered in silkscreened linen, Orlando sits on a set of black stairs. He’s a body and image at once. Carefully posed but weirdly absent from himself, Elizabethan but also filmic, he’s caught in a series of mismatched acts. Noonan’s breed of performance art has that effect. It collapses theatrics into one precise moment, making them denser and more layered than they would be if actors could dance, sing, talk or even move. His approach is almost cruel–it puts personality in a permanent state of limbo–but it’s also richly complete in the way it allows “so many mixtures of imagery” to co-exist indefinitely.