The City Proper

L.A. Expanded: Notes from the West Coast

A weekly column by Catherine Wagley

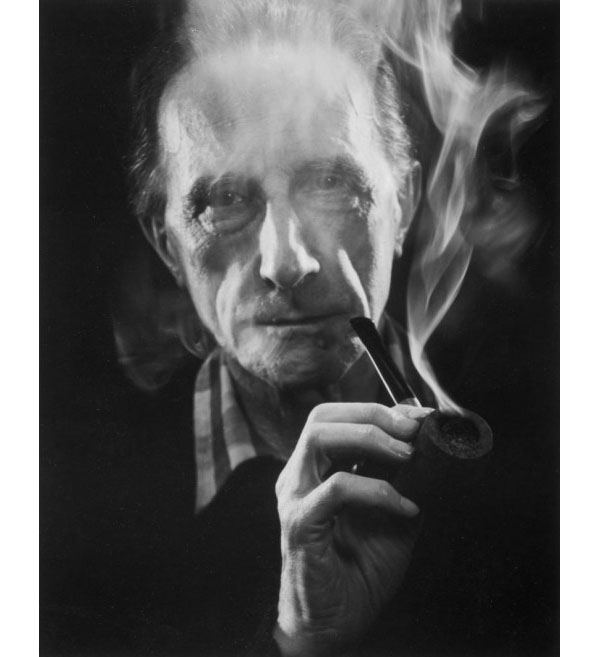

Ger van Elk, "The Co-Founder of the Word O.K.-Hollywood," 3 color photographs, 1971.. Courtesy the Artist and Margo Leavin Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: by Brian Forrest.

The first time I visited downtown Los Angeles, I was surprised by its bareness. A friend and I, both of us art students, had driven in from Claremont for an opening, tackling the congested Santa Monica freeway for the first time, too. A fellow student and L.A. veteran had warned us that, even if we experienced smooth sailing through Covina, we’d hit an out-of-nowhere stand still once we’d “cleared that hill and past the Westfield [mall].” He was right, and we slowed to a laborious crawl 20 miles from the city. Braving traffic felt like initiation and we were proud of ourselves. However, once we arrived in the city proper and exited the I-10, all the people seemed to evaporate. The galleries we wandered through may have been well-populated, but, otherwise, downtown felt weirdly gutted of life.

At one point, my friend and I stood outside a café, staring up into the windows of what looked like an abandoned warehouse. A transient stopped to stare with us. “Amazing how they built this city up, huh? There’s no space left nowhere,” he commented, misinterpreting the source of our awe. We agreed, however—it was amazing that a city that had been so recently and extensively built up and out could feel both congested and desolate at the same time.

A comparable sense of lived-in bareness characterizes The City Proper, an exhibition of contemporary photography of SoCal’s urban landscape currently on view at West Hollywood’s Margo Leavin Gallery. Curated by James Welling, known for translucent and prismatic photographic experiments with color, the show mainly features L.A. artists and loosely responds to New Topographics, a now seminal exhibition that first appeared at the Eastman House in 1975 and was rephrased by LACMA in 2009. The photographers in New Topographics, among them Lewis Baltz, Frank Gohlke (who also appears in City Proper), and Robert Adams, were preoccupied with man-altered landscape and replaced the humanitarian poetics of the West’s earlier documenters—think Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, or Dorthea Lange—with calculated, uninhabited aloofness.

The City Proper is perhaps less aloof than coolly curious. It includes an array of angular buildings, empty city streets and urban nooks and crannies. Ger van Elk, an artist whose fascination with man’s role in modern landscape once led him to travel a canal via a small rubber dinghy and, later, navigate the Atlantic, has contributed a series of three color photographs, collectively titled The Co-Founder of the Word O.K.-Hollywood (1971). Each image has that vintage, William-Eggleston-worthy orange-heavy coloring, and each shows van Elk posed in profile to the right of a framed bubble letter “O.” He has propped up against a pole, column or building facade, and raised his own arm and leg to turn his body into the letter “K”–so he is “O.K.” on a residential street, outside a convenience store and a block from the Hollywood Colonial. Though cars line the streets and colorful signs interrupt the skyline, few other bodies appear in the shots. It’s as if van Elk is a pioneering tourist in a man-made but barely occupied amusement park.

Zoe Crosher’s series of LAX prints also have a vintage ambiance to them, though they were made between 2002 and 2005. They depict slightly gaudy hotel rooms near the airport, which means seas of cars and the occasional ascending plane can be seen from the windows. The camera always looks out—out the window, or out the sliding door—and the result is a vague feeling of yearning, but since there is no specified subject to attribute the feeling to, it just floats languidly on the image’s surface.

Brandon Lattu‘s angular, faux-minimalist boxes take bareness into three dimensions, presenting squares or rectangles covered by a solid color except for the murky photographic images of palm trees or city drags that peek out from the boxes’ edges. A similar nonsensical formalism characterizes Shannon Ebner’s Fixed Knot Fence, Los Angeles (2010), which shows a chain link fence crowned by barbed wire standing in front of a bare white concrete wall. Dry knotty tree branches create a formal frame around the perimeter of the image, making the scene geometrically, romantically rustic.

Brandon Lattu, "Random Composition 12-105," Pigment, polypropylene, paper, polystrene, and wood, 2010. Courtesy of Artist and Margo Leavin Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

In his quietly sentimental book, Why People Photograph, Robert Adams, one of the first to train his lens on the man-altered landscape, tells a story about a friend, a photographer who remains unnamed. This friend used to take pictures along country roads by sticking his body up through the sun roof and steering with his feet. No one could convince him to abandon this practice, because, to him, the view felt so right and so real. I imagine the resulting photographs showed little direct evidence of the recklessness that made them. In fact, they may have been as austere as Adams’ own images, or as uninhabited as the images in The City Proper. But when Adams says his reckless friend inspired him to take “grand, unsafe pictures,” he more or less means he wanted his images to feel right, to capture the mood of a space as uninhibitedly as possible. The photographs in The City Proper are insouciant, open, and characterized by a certain bravery. They show the cityscape to be a technological, gridded construction that, while made by humans, does not necessarily need a human presence to sustain it, but they also seem bent on conquering the city in a way that suggests urban impassivity can be subverted by those determined to understand it.