The Death of the Post

If video killed the radio star, the advent of the internet has certainly managed to tear the post to bits. In our pervasive, high speed, digital world there is an undeniable convenience in instant communication, but with this power comes a price – a price paid by the death of the handwritten letter and the sense of intimacy that accompanies it.

Hidden within an abandoned Post Office in London’s East End of Hackney we stumble upon Posted – a temporary exhibition space that explores the intersection of art and the post and examines the ‘dying art of correspondence through letters.’ The current exhibition by director and curator Julia Royse, Please Write, fights against this, refusing to give up on the post, by gathering together artists whose work compiles a compelling case for the post and strives to remind us of the power of these handwritten messages.

Jane Simpson, Loving Letters, 2010. Installation with objects and letters. Courtesy of Posted Projects.

The most gripping work in the exhibition is Jane Simpson’s Loving Letters, an installation comprised of the old writing desk of the artist’s mother overflowing with letters Simpson has received from her. The letters she has received from her ailing mother do not always paint a pretty picture, so Simpson has taken them, torn them apart and attempted to reconstruct them to read what she wishes they would say. Her struggle, and failure, to reconstruct memory and reality is discernible; the letters now contain pleasant sentiments, but the distinguishing scars of the process shroud their surfaces. It is not as easy to cut and paste paper as we have become accustomed to doing in a Word Document, and the residual jagged edges resemble something closer to a pre-digital age ransom demand, than a letter from a loving mother.

Tim Noble and Sue Webster, Comparing Mothers, 2010. Letters from our mothers, ink on paper. Courtesy of Posted Projects.

Tim Noble and Sue Webster’s work, Comparing Mothers continues to explore the maternal relationship. The artists construct what functions as a family portrait by juxtaposing the letters each artist has received from their mother. The emotional, passionate, artistic side of Noble’s mother comes through as she writes madly all over the page, regaling in detail, how she inadvertently killed a hedgehog while mowing the lawn – and the emotional and psychological impacts of doing so. The letter from Webster’s mother is far more removed, constructing an emotionally an clinical letter of pure facts and forced sentiments. The letters seem to provide us with some insight into the relationship each artist must have with his or her mother, and we grasp onto every word, hoping to extract something about the artists from them.

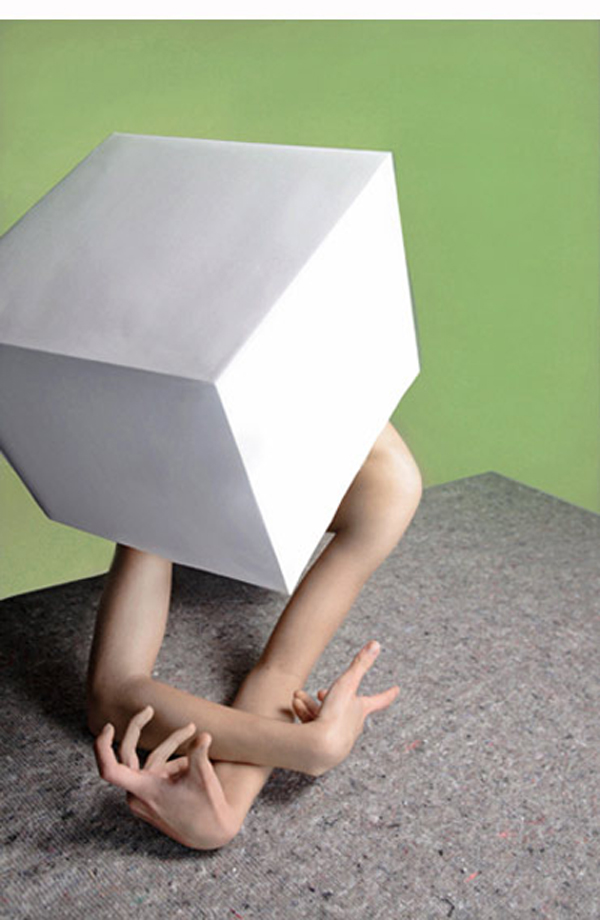

Jessica Piddock & Izzy McEvoy, Still, my murder will appease them, 2010. Ink, woven paper, coat hanger, glue. Courtesy of Posted Projects.

Jessica Piddock & Izzy McCoy’s work hanging in the front window, Still, my murder will appease them, reminds us that not everyone is privy to the digital technology we take for granted. Here, they have written letters to prisoners on death row, those individuals for whom the post is one of their only methods of communication with the world at large. The artists have taken their letters they have received in response and woven them into what resembles a prison uniform. These letters, now unreadable, contain the thoughts of the condemned; letters we both desire to read, yet both fear and are unable to do so.

The art of the letter may be dying, but it is not yet dead. The rarity of letters gives them a certain aura; there is a personal, romantic, nostalgic sense that surrounds them. There is something about holding a handwritten letter – the beauty of the paper, the smell of the ink, the sharp creases in the paper – that a blog, tweet or email can never quite capture…

I do assure you that the irony of writing about this online has not escaped me.