Interview with Nina Beier

In the first moments of our meeting, Nina Beier ambushed me. “Do you mind if we go over to the tea garden next door?” she asked, “Some friends of mine are there and we can all talk together.” I was alarmed at the prospect of a one-on-one interview conducted in a group, but I held my nose and jumped in. It was only through talking with her—and with Chris Fitzpatrick and Post Brothers (both are authors of wall text in the gallery)—that I understood exactly how central this kind of decision is to her working methodology.

To understand Beier’s oeuvre you have to be willing to investigate, to read, to dig, and to allow other voices to participate. Her exhibition What Follows Will Follow II at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts is divergent in media but parallel in its concept. For example, the core of the exhibition consists of eighteen framed chromogenic prints, views of a previous exhibition. On the wall outside the main space is On the Uses and Disadvantages of Wet Paint (2010), a rollered patch of paint on the wall, repainted every few days with different colors from YBCA’s existing stock of paint. The Complete Works (2009-10) has a retired dancer re-stage all the dance moves that she can remember, in chronological order. Beier’s work is iterative and reiterative, making the work perform itself again and again in order to hold a kind of meaning open, for itself and for the viewer.

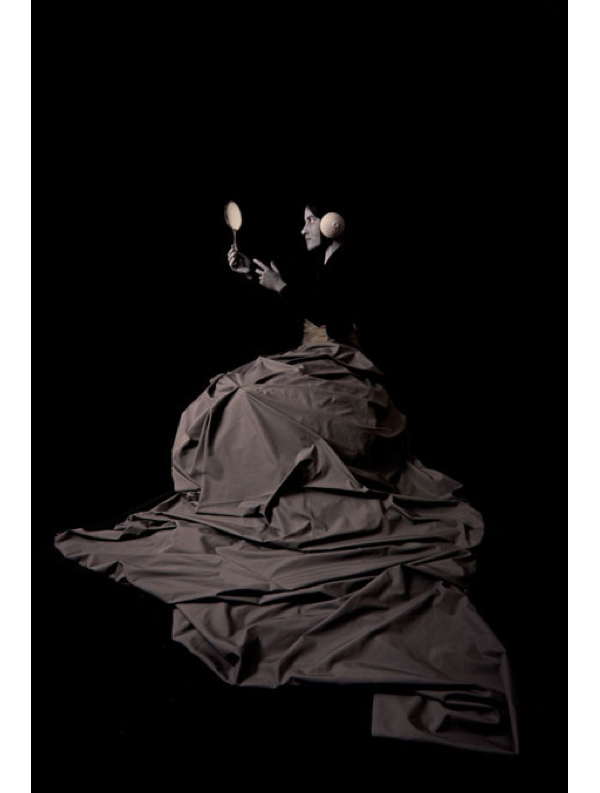

Nina Beier, On the Uses and Disadvantages of Wet Paint (2010). Paint, increasing dimensions. A patch of paint on the wall iteratively painted over with a different color from the stock of the Yerba Buena Art Center.

Bean Gilsdorf: Let’s start with the basics—your work is so materially diverse. If someone asks you what you make, how do you answer?

Nina Beier: [laughing] Only in America do I get this question! I usually say that my work is conceptually based and takes any form except painting…but I guess that’s not even true anymore. I am wary of self-mediation though, because conceptually conceived work is already far too self-conscious. The art needs to work as a project: to read, to misinterpret, to reinterpret, that’s how you get closer to the idea of a show.

BG: The Extreme and Mean Ratio sculptures and What Follows Will Follow are projects that have the possibility of being unfinished forever. How do you resolve to stay unresolved?

NB: In the gallery now [at YBCA] there is a wall painting, it gets painted over every few days. It’s never-ending and will continue even long after I have a claim for it, because that wall will be painted now, but also will be painted for subsequent exhibitions. So in a way, it will survive for as long as the exhibition space exists. My process is coming from a direct frustration—as artists we want to explore something that is alive, but normally in the art system the work is supposed to have a final destination, and it freezes. On the issue of staying unresolved, I guess I am not the first artist to struggle with fitting a living and changing practice into a framework that demands final answers.

BG: So what is your process?

NB: All the things that are completely unbearable about the system, that’s what I want to work with. The artwork is autonomous despite the attempt to claim its rights. When I look at my existing work it is not uncommon that something has changed since it was made; it could be its context, itself or even me. I respect the authority of the [extant] work, but I like to believe that mine trumps it. I should have the freedom to change it. For example, I’ll change a title if I don’t think it’s fitting anymore.

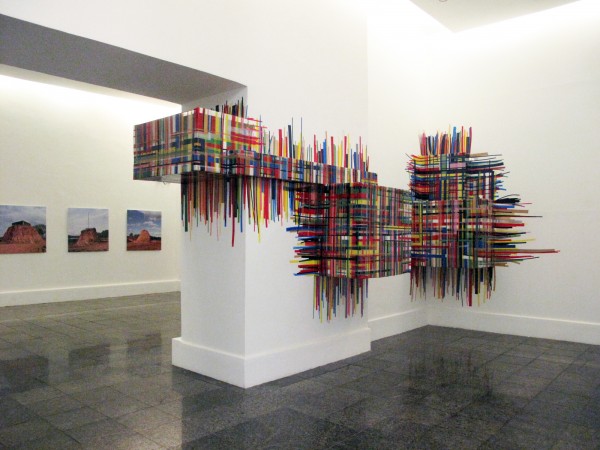

Nina Beier, What Follows Will Follow II (2010). Installation view of 18 photographic C-prints, various dimensions. Framed photographs of work extracted from the installation shots of a previous exhibition.

BG: You’ve been quoted as having read the theories of Walter Benjamin and Roger Caillois. Do you think of your work as theory-driven?

NB: I read, but not conscientiously, I have to admit. I use writing for inspiration and I rudely mix and match to make it fit my current thinking. But I would hate to think that my work would be an illustration of any theory.

Chris Fitzpatrick: It’s more like dislocated footnotes, to approach without explaining.

NB: I guess you need to have an ideal viewer in mind when working, someone to assign the ability to read both the conscious and unconscious signs embedded in the work. For me this viewer has recently materialized in the form of Post and Chris [gesturing to the others]. Art relies so heavily on its reader, it is hard to ignore when making an exhibition. And since my work ‘is like concentric crates, which depend on where they are unpacked or who looks inside.’ Okay, that was a bad attempt at quoting Chris and Post’s first wall text, but the point is that they are the people who are stuck with making sense of it all, these days.

Post Brothers: Instead, there are points on a map to locate—and to contradict and compliment.

BG: Do you feel you are playing a game with the audience?

NB: No, a game would imply that I have a master perspective and I don’t want to claim that. This exhibition experience could play out in many directions; for example, the wall text [rewritten repeatedly by Chris Fitzpatrick and Post Brothers and replaced throughout the exhibition] is all in their hands. It is a space that welcomes even misinterpretation and contradiction.

CF: Unlike a game, there’s no objective to achieve, it’s not shutting down meaning. But we are playing our parts, if you will, in the play of the exhibition. There are platforms and frameworks, but it’s not the type of exhibition where works arrive finished. There’s a lot to respond to.

NB: My work tends to be built on some more or less logical premise, but it would be really sad if it ended there. I try to start something and there is nothing better than when it is taken on the route of over-interpretation, an attack of the mind, like the incredible places that these guys’ minds can go. It’s what any work of art would wish for.

Nina Beier, What Follows Will Follow II (2010). One of 18 photographic C-prints, various dimensions. Framed photographs of work extracted from the installation shots of a previous exhibition.

PB: There’s a temporal interaction here. The work resists the historicity of a document fixed in time—instead, there’s a translation from one object to another.

NB: The initial exhibition What Follows Will Follow presents a confusion between the object and the image, between the map and the territory. The story of a one-to-one map is told in the press release and consequently in the exhibition space by the staff of the gallery, raising the question—is the retelling the story, or is it a representation of the story? The sequel What Follows Will Follow II is limited to the perspective of the photographer’s lens, but it opens up to its viewers in many ways that its more heavily loaded predecessor couldn’t. Through their processing, the images have become more or less abstracted, in some cases to the degree where all you can see in the dark framed monochrome print is your own reflection.