Deborah Willis and Hank Willis Thomas, Sometimes I See Myself In You, 2008. Courtesy of the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts and Culture.

From October 8th, 2010 through January 23rd 2011, The Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts and Culture in Charlotte, North Carolina, presents an exhibition by two creative duos of mother and son artists entitled Progeny Two: Deb Willis and Hank Willis Thomas and Fo Wilson and Dayo. This exhibition is an exploration of the creative process per se and the context of social and cultural issues that may effect this process. The creative processes for artists vary, of course, in accordance with the predispositions, inclinations, insights, and experiences of the individuals themselves and their respective worldviews, cultural interactions, and social intuitions. However, when artists have powerful relationships with each other, this creative mixture can result in extraordinary, unanticipated results that offer insights into aspects of human experience often camouflaged in our day-to-day interactions.

The Gantt Center’s Progeny Two exhibition offers a surprising collection of collaborative works generated by both creative mothers and their artistic sons: one pair is award-winning photographer and archivist, Deborah Willis and her son, noted photographer, Hank Willis Thomas, and the other is sculptor-furniture designer/conceptual artist, Fo Wilson and her son, film and video director Dayo (Dayo Harewood). In the differing media employed by any artist, used to translate ideas into objects or experiences, what we as audiences may be shown as well as what we may not be shown may be equally powerful factors relevant to the shaping of our responses. In Progeny Two, the mother-son duos are engaged in a interaction with what I reference here as “present absences.” In particular, Deborah Willis and Hank Willis Thomas engage with the concepts stemming from the supposed writings of William Lynch, a notorious, fictional, 18th century professional “slave breaker.” However, the appearance of the letter established the association of the character William Lynch with the topic of the practices and social processes determining a predisposition to psychological self-destruction among African-descended peoples forcibly subsumed into Euro-centrist cultures.

Fo Wilson and Dayo, Sarah's Lament, 2008. Courtesy of the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts and Culture.

Fo Wilson, in her turn, works with her progeny, Dayo, in a discourse with the memory of Sarah Baartman, the legendary so-called “Hottentot Venus”, a South African Khoikhoi woman literally killed by race-based and racist curiosity.[1]

The personal narrative of both single working African-American artist-intellectual-mothers shares the feature of successful sons, who have matured in a culture that may be construed as inherently hostile to them, their African ancestry, and their social status. Ideas of family, survival, the roles of mothers as well as fathers, of generative and creative life, and of memory are the themes explored by this exhibition; these themes are of vital importance to contemporary discussions of American cultural development and on-going issues of cultural identity, the structuring of what is and what is not included in historical narratives, and even the importance and need for preserving ethno-centrist cultural institutions such as the Gantt Center itself.

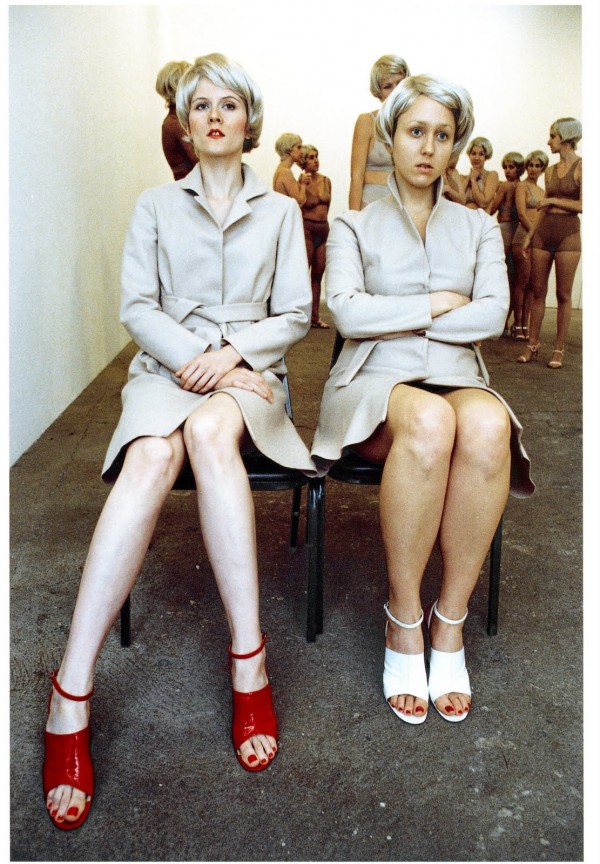

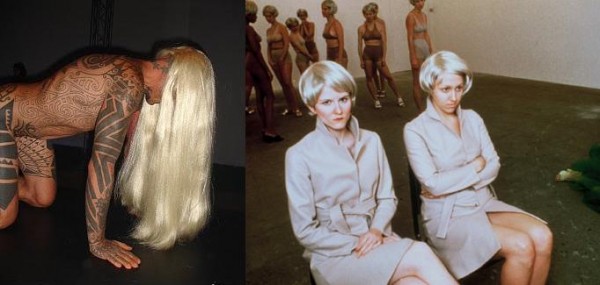

Fo Wilson, Hottentot Not!, 2008. Courtesy of the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts and Culture.

The exhibition title addresses the fact that two sons, literally two “progeny” work with their mothers to bring to the fore issues of contemporary American experience, which have their roots in certain cultural preoccupations stemming from the confusing, inherited traditions and myths of slavery. Willis and Willis-Thomas provide interesting commentary on capitalist praxis, folk knowledge, and the complications shaping our sense of personal identity, social relationships, and popular cultural interpretations of history. Fo Wilson and Dayo concentrate on the problems of the objectification and commodification particularly of the female body, and more specifically the legacy of curiosity concerning the body of the African female (and that of her progeny) as an exotic, or unusual type.

The principal collaborative piece in the exhibition presented by Fo Wilson and Dayo is the multimedia work entitled Sara’s Lament in which Wilson has created a fictive letter creatively written in the artist’s interpretation of the voice of Sara Baartmann, a South African woman transported to Europe for exhibition to a curious public. Wilson/in-the- guise-of-Baartman writes to implore contemporary late 20th and early 21st century African and African-American women to desist from any active complicity in purveying the objectification and commodification of their bodies as tools of capitalist exploitation. Perhaps ironically, Wilson’s son, Dayo is a director of contemporary, commercial music videos and films, precisely those media most often used to abusive ends and destructive purpose with regard to affecting construction of internalized representations the feminine body-imagery. Examples of such videos are provided on small screen images which include passages extrapolated from the highly sexualized music video idiom, including the “infamous” L’il Kim (Kimberly Denise Jones ) video, “How Many Licks?”, a lascivious musical homage to the act of cunnilingus and both a celebration of feminine sexual freedom and a boasting narrative of irresponsible sexual activity.

Fo Wilson and Dayo, Sarah's Lament, 2008. Courtesy of the Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts and Culture.

Wilson’s fictive Baartman letter directly addresses the assumed degradation of the female body and mind by the commercialization of strongly sexualized content for public consumption. Wilson’s concern appears to be for expression of the concepts of beauty and desire, and the potential for social abuse deriving from a destructive, sexualized gaze, specifically at the female body. Sara Baartmann was a victim of this sexualized gaze and an implied analogy is established to suggest that she is in some sense “like” L’il Kim, who is shown in the video as undergoing a mechanized process (a metaphor for a series of invasive plastic surgeries that Kimberly Jones actually underwent, having her body completely reconstructed in accordance with the sexualized aesthetic preoccupations of the late 20th, early 21st century), both women are presented as “victims” of capitalist exploitation and its destructiveness. Of course the choices made by L’il Kim in the tradition of Josephine Baker, who also engaged in a self-imposed exploitation of sexualized and racially structured cultural myths for personal profit, exploiting her would-be exploiters, and the injustice fostered off onto Sara Baartman, who had nothing like the possibilities of choice offered to Baker and Jones, are quite radically different in character, and these intriguing issues raised by the works in the exhibition are precisely what ought to be discussed by a larger public.

Related to the mixed media work of Sara’s Lament is a furniture installation placed at the center of the gallery. A letter dated 1815, providing information on Sara Baartmann is suspended above the table. The table is a visual representation of both the idea and action of support, and is also shown as a signifier of a utilitarian object, in spite of its pleasing aesthetic dimensions, and it thus offers an implicit analogy with the female body. Indeed, the table is intended to symbolize the physical presence of Sara Baartman as a beautiful “object” of observation, even contemplation and insidiously, an object of “use”.

Hank Willis Thomas, Branded, 2008.

Other especially evocative works with in the exhibition include Hank Willis Thomas’ Branded Series, specifically the semi-sculptural triptych of three simulated credit cards, embedded in thick plastic, and set up-right on their lower edge, alluding to the contemporary “enslavement” of the American public by consumerism and debt. In the first credit-card image, Willis-Thomas uses his own name on an artfully fabricated American Express Card imitation, bearing a date of 1619 and entitled Afro-American Express, showing images of slave ships. The 1619 date references the early documentation of legalized slavery in the Virginia colony of the Americas; in addition, a Discover Card dated 1492 and issued to Cristobal Colon, the Spanish form of the name of the Italian explorer, Christoforo Colombo, or in English, Christopher Columbus, whose mention alludes to the search for gold and religious converts that fueled the initial phases of the capitalist enterprise that would eventually lead to the extension of the Euro-centrist model of human slavery into the new world. The third simulated card in this series is the Chase Master Card with a date of 1712, and bearing the name of William Lynch. However, the card shows images of the authentic types of slave restraints, including shackles, constraining bits, and collars that were an essential part of the true methodology employed in a process centered on degrading, coercing, and forcing enslaved persons into submission to the will of “masters” for the financial gain of the latter. Again, myth, fiction, fabrication, fact, and truth overlap in a manner consistent with the reality of American (and “African-American”) experience.

Willis offers compelling feminist critique in a photographic sequence entitled, A Good Man, with images shown as if taken from a proof sheet and numbered 34A -36A. The first image, presented with an explanatory legend beneath it in 34A suggests a woman taking a space from a “good man” (an allusion to talented women being perceived as “taking” jobs away from equally or less qualified males?), and is a self portrait of Willis, shown as if conjuring a pregnancy. 35Aa bears the legend, “you took the space from a good man,” and shows the hands of a male placed upon the impregnated abdomen of the photographer herself, the face and body of the male figure are never shown.

Deborah Willis, The Mother Wit, 2008.

A compelling poetic directness is achieved in the simple digitized morphing shown in the large photograph, Sometimes I See Myself in You, in which, depending upon whether the viewer does a “classical” Western reading, from left to right, or a more atypical reading, from right to left, we see the image of son morphing into mother (left to right) or of mother morphing into son (right to left) with a combined image of the features of the two as a single individual placed centrally (a visual realization of the collaborative action of mother and son and an allusion to the collaborative fusing of father and mother).

In a final series of photographs produced jointly by Deborah Willis and Hank Thomas entitled Words to Live By, combined with The Mother Wit Series, the aphoristic wisdom of the ages is provided beneath images of the lower halves of a wide variety of ethnically diverse representations of faces accompanying gem-like folk insights such as “ Better no man than the wrong man…” or “Amor de lejos, amor de pendejos…”, translatable as “Long distance love, fool’s love..”, or “Honey, if you don’t know what you’re talking about, listen and keep your mouth shut!…”, or the ever-wise “You can’t carve rotten wood!…”, and “If it don’t start right, it won’t end right!…” offer the kind of folk-lore laden, old-wives-tales information a traditional mother might offer her child.

Deborah Willis and Hank Willis Thomas, Words to Live By, 2008.

The exhibition as a whole aggressively addresses the challenges to personal integrity interrogated by the illusion of a spurious claim of absolute power of one human being over another, explored in this context with reference to the inhumanity and the horrors of slavery. This combined with the myths, facts, folklore, and mother-wit concerning the truth of falsity of a narrative positing claims either of the absolute dominance of one group over another, or the powerless dependence of one group victimized by another and the intrinsic difficulties of an exploitative systematic capitalism that placed profitability over people are the issues these artists intend for us to respond to, reflect upon, assess and discuss.

The exhibition presents multiple levels of allusion and investigates uncomfortable, complex, emotionally charged areas of the American cultural narrative with a clearly sympathetic interpretation of the socio-cultural extensions stemming from the diverse narratives of the African diaspora. True exploitation, like the fictive cruelty of William Lynch, even within the African and African-American communities, continues to impact the generation of an American cultural narrative in our own time. Further, Fo Wilson and Dayo present a discursive approach to the tragedy of Sara Baartman’s story which underscores the countless tales of cruelty and the perversely inconsiderate, anti-humanism of the extensions and aftermath of a race-based slave system. The persistence of the issues alluded to in the exhibition merits conversations around this show about mothers and sons (and by extensions fathers and daughters and our entire community as a human family). We are all implied by the content and are thus complicit in the social cruelty and ignorance the artists allude to using creativity, humor, and most importantly, with an evident love for and desire to transform society through their works. If one convert is any indication, then I confess I found out a great deal about myself and the need to investigate the history, myths, legends, lies and facts of our shared culture. Of equal importance with what is shown in the exhibition are the necessary conversations that it must inspire concerning our awareness of the complicated phenomenon of the “presence of absence”.

Writer and critic Frank Martin is a member of the Association Internationale des Critiques d’Art (AICA) and a periodic contributor to DailyServing.com.