Leave it to Beaver: Ridykeulous at INVISIBLE-EXPORTS

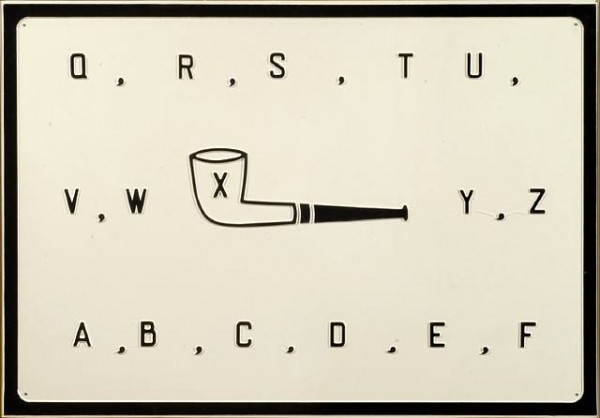

Ridykeulous, The Advantages of Being a Woman Lesbian Artist, 2007. Photo courtesy of INVISIBLE-EXPORTS.

It’s par for the course for blue-chip galleries to mount so-called “museum quality” exhibitions, and hardly a surprise when they coincide with auctions and estate holdings. Readykeulous: The Hurtful Healer: The Correspondance Issue at INVISIBLE-EXPORTS is just as historically potent without being market driven. Founded in 2005 by artists Nicole Eisenman and A. L. Steiner, Ridykeulous has gained consistent momentum, and this is their strongest show yet. Part community action center, part archive, part open can of whoop ass, the show includes about forty artists and runs roughshod past The Venus of Willendorf, David Wojnarowicz and the Guerrilla Girls before landing squarely in the present.

Readykeulous, The Hurtful Healer: The Correspondence Issue. Installation view. Photo courtesy of INVISIBLE-EXPORTS.

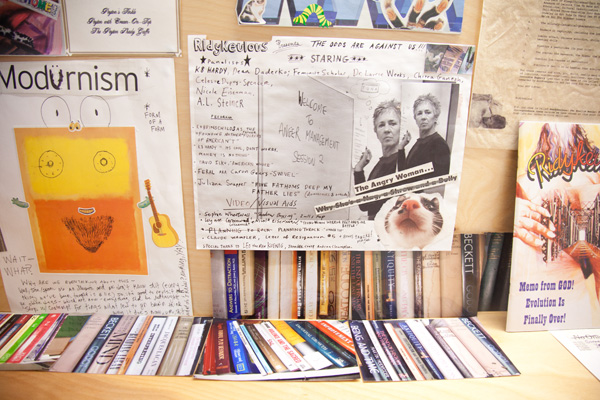

Even though the show comprises mostly written correspondence, those accustomed to the visual swagger of a typical Ridykeulous affair will not be disappointed. By including work from the 70s forward, it’s almost as if Ridykeulous is upping the ante on a previous generation’s discontent. A rather calm and verbose letter by David Wojnarowicz floridly articulates his disappointment with not getting public funding. A Carolee Schneemann letter from 1978 bluntly asks a foundation to pay her $25 to donate her archive, but she writes in a fairly civil tone. In contrast, Crystal Catastrophe, 2011, a letter/image by Allyson Mitchell and Deirdre Logue begins, “DEAR ASSHOLE”. Eisenman and Steiner pull a bit of one upwomanship on the famed Guerrilla Girls in The Advantages of Being a Woman Lesbian Artist, 2007, which hilariously updates and defaces the Guerrilla Girls’ The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist from 1989. Compared to the self-assured irreverence of many of the artists in this show, Guerrilla Girls, once formidable, now seem kind of cartoonish and tame.

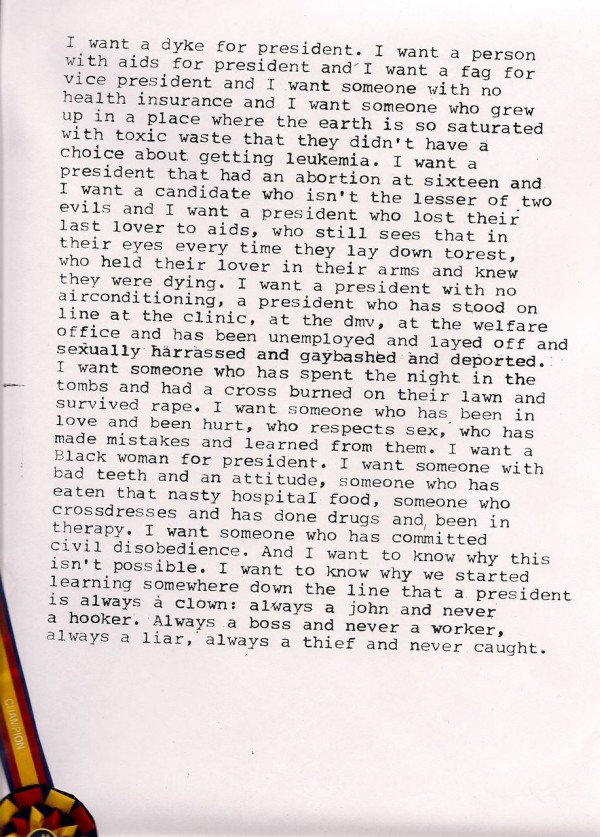

But there’s a lot more to this exhibition than in-your-face rage. Many of the letters on view are potential paradigm shifters. Zoe Leonard’s I Want a President, 1992, in which she hopes for more humane criteria for presidential candidacy is both heartbreaking and poignant. Kara Walker’s writing stares into the core of her artistic intentions without the visual drama of her trademark silhouettes. Nicola Tyson transforms a letter to a male harasser into sculpture by hanging it on a noose. When a passive aggressive audience member writes to Nao Bustamante, feigning concern for a participant in one of her performances, the artist wryly replies, “This is like emailing a magician after an illusion and seeing if the girl died from being sawed in half.”

Kathe Burkhart, Suck My Dick: from the Liz Taylor Series (Candid shot), 2004. Photo courtesy of INVISIBLE-EXPORTS.

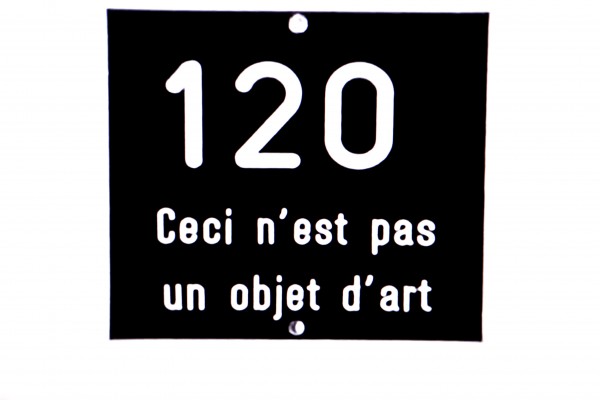

Admit it—when artists write about their work, its often pretentious, boring and has little to do with the actual art. Thankfully, in this show, the artists’ candid thoughts and impassioned rebuttals are the art. And no one’s trying to hide or act nice for the art market. As K8 Hardy says in Dear Reena Spaulings, “I don’t care if my shit is unprofessional or tacky. My work does not come from a fucking wallet.” Nothing is more direct than Kathe Burkhart’s Suck My Dick: from the Liz Taylor series (candid shot), 2004. Big black dildo protrusion aside, the work is composed of a lifetime’s-worth of partially burned rejection letters, some of which get fairly mean. One from Metro Pictures simply reads, “not our cup of tea.”

Despite the high volume of malcontent on display, the real power behind this show is humor. The exhibition is essentially positive and inclusive, and it maintains a visually dynamic installation amidst all the reading and display cases. Wall scrawls, collages, and tacked-up photocopies create a swift pace that counters the slowed-down experience of reading. Cut outs of ancient goddess figures help punch up a case full of letters. A frieze of book covers from Valerie Solanas’ Scum Manifesto guards the entrance to the video corridor, where a folder labeled “Man Art” (samples include dinosaurs, a Lisa Yuskavage ad, and other offenders) lies on top of a searing video by Genesis Breyer P. Orridge. In the back gallery, a wall case has been punked out with flyers and drawings, like the coolest public library display ever. The gallery is smallish in size, yet this installation manages to pull off a balance of slapdash improv and thoughtful placement.

A lot of shows tiptoe around ideas of protest, but they tend to feature artists who rarely get into the trenches. These days it can even seem like making political art is a mannerism—an excuse to make cool posters and use typography that rarely sacrifices marketability. Ridykeulous doesn’t pull punches. They understand that if you don’t like the art world you’ve been given, you’ve got to make your own. And they don’t fucking apologize for it afterward.