Sad Sack: An interview with Ryan Travis Christian

Chicago-based artist Ryan Travis Christian creates amazingly rendered drawings that employ an amalgamation of sources, all collapsing and folding in on one another. Ryan freely adopts cultural signifiers, both high and low, and fractures them to the point where anything can exist on the same page, regardless of its origin. The artist currently has an exhibition on view, titled Sad Sacks, at San Francisco’s Guerrero Gallery. After viewing the exhibition, I caught up with Ryan to talk about the process for creating these highly imaginative drawings, personal stories of the absurd which fuel his inspiration, and the myriad of upcoming projects that he has coming down the pipeline.

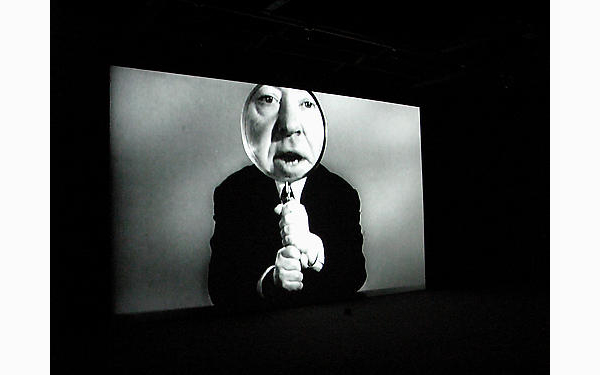

Ryan Travis Christian, “Optical Illusion #4 (Sad Sacks)”, 2011 / Image courtesy of Guerrero Gallery

Seth Curcio: So Ryan, It is good to finally chat with you! You know, I first came across your work about two years ago in Los Angles at the now closed Synchronicity art space – across the street from one of the best ice cream spots in the world, Scoops. I was there with a good friend of mine and he was raving about your drawings. Since then, I have kept my eye on your projects as they pop up in galleries all over the country. There has been a lot of development in your work over the past few years and your visual vocabulary is constantly expanding, evolving, co-opting and consuming. Walk me through the process of creating one of your drawings. Do you approach it purely through intuition or are they carefully planned from the start? I have read that you create an abstract problem for yourself and then solve the problem during creation…. this sounds really interesting, but exactly what does it mean?

Ryan Travis Christain: Likewise! Haha, for the record… Synchronicity (run by two near and dear friends of mine) is re-opening kitty corner from their old location in a freestanding building facing Scoops, & now that you mention it, i could really go for a scoop of pear ice cream, damn that place is good.

Anyhow, as far as approaching a drawing goes, I’ve been writing a lot of brief little notes to myself on scraps of paper, stories, memories, phrases I’m fond of. These scraps are everywhere! I like to sit on them for awhile and see what comes back to me a second or third time, figuring there’s some sort of extra weight to that.

Taking said idea, I then begin to build up a surface on the paper, there are a decent amount of layers beneath the finished product. The “abstract problem” is more or less a mess that I’m forcing myself to respond to. Expressive mark making, rubbings, or even something like a big fat x in the center of the picture plane, provide me with a loose structure that I can begin to plug my vocabulary into. It’s nice to be able to retain some of the gestural quality of the “problem” and have that interact with the concrete visual elements. It definitely gives the drawings some sort of energy.

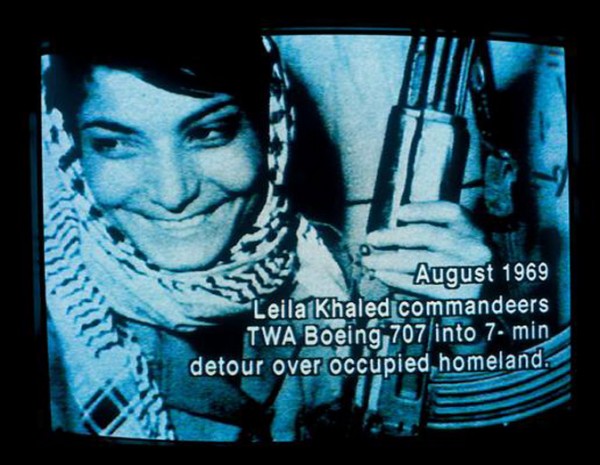

New Bikini Jam #2″, Graphite on Paper, 2011 / Image courtesy of Guerrero Gallery

I’ve made it a point to stop pre-conceiving a specific image to achieve. I used to drive myself crazy that way, trying to meet my brain’s own high standards. I feel like that kind of sucks the fun out of it, as opposed to just seeing what happens. I think that’s a really great way to go about making something, you can stumble across all sorts of things that way and often surprise yourself. There is a lot of of freedom in this approach. I read recently that Cormac McCarthy tackles his writing in a similar fashion.

SC: So what are some examples of the phrases that you write down? There is a definite dark humor that permeates your work. Do the phrases contain humor too, or are they totally random? Also, I want to know more about your visual vocabulary. Where do you pull your sources? And, is anything up for grabs?

RTC: Oh man, the phrases are infinite, they are pulled form everywhere, I probably use about 1% of them overall. Sometimes they are humorous, sometimes totally random. Some examples are “juice loosener”,”walks in forrest, sleeps in the river”, “wooden mexican”, “dramamine”, “old dro”, “snake men”, “demon bag” (these are ones visible from where I’m typing). I guess they’re probably funnier to me since I know what they specifically reference, but I’m not trying to be funny, I just want to retain these fleeting thoughts and 2-3 word phrases do the trick quite nicely. It also happens that some of these “ideas” are just actually funny, humor trumps beauty in my mind as far as eliciting an emotional response from a viewer and I’ve always been most drawn toward humorous work.

Ryan Travis Christian, “Binocular View #2″, Graphite on Paper, 2010 / Image courtesy of Guerrero Gallery

Yeah, anything is up for grabs, I don’t see any point in limiting myself to a specific set of sources, but I do definitely tend to wind up gravitating toward certain things repeatedly. I find myself wanting to draw cars, sex, homes, lawn care based activities, and vague landscapes/shallow spaces the most. I guess these are the things I think about/recall most often and the landscapes/spaces are perfect stages to place the narrative. Narrative wise my source is mainly memory, object wise my source is also mainly memory, but from time to time I’ll steel someone’s story or print out a picture of a rose to draw from. Thought I’ve noticed as time goes by, other sources start to creep in slowly and become a staple part of the vocabulary. So it’s constantly evolving, at glacial speeds.

SC: That’s interesting. I usually link words like car, homes and lawn care to suburban culture. These are all mundane activities and objects that fill basic suburban life. Yet I feel that there is also an anxious feeling of being trapped in some sort of bad dream, where absurdity takes over seemingly innocent activities — maybe this too is a product of suburban culture! It’s evident in works like Creepers #1 where a typical backyard melts into a subversive landscape. Since you mentioned the source of your narratives being based mainly in memory, I have to ask, what happened to you in the past that led to these types of visual stories?

RTC: Spot on! The surburbs (where I grew up and still live) are like a bad dream or a weird one at least. You have rural and urban influence, lots of space, redundant store scapes and infinite neighborhoods. Suburban culture is fucking boring when you are young and angst-y, it forces you to make your own fun. You have to hang out in the forrest or sneak out and run around at night and be absurd. When your town or city or whatever isn’t brimming with garbage and filled with hobos and police sirens, happenings are much more noticeable.

But suburban lifestyle aside, I feel that story telling is the highest form of art, drinking beer with friend comes in a close second Marioni!. So that’s what I do, take the best ones and draw em’. I don’t usually broadcast what a drawing is specifically about, I like that people can make their own associations with the imagery, but since you asked nicely, I’ll tell you one.

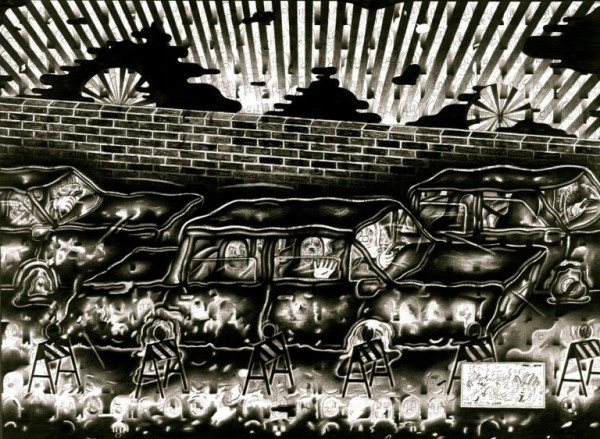

Ryan Travis Christian, “Creepers #1″, Graphite on Paper, 2010 / Image courtesy of Guerrero Gallery

Creepers #1 happened on Halloween of 2001, at the time we had these neighbors who were total crabapples, a real miserable middle-aged couple, the entire block would agree with me on this statement. My parents and I were returning from an early dinner and kids were all over the place trick or treating. As we pulled into our driveway, I briefly glanced at my neighbors house. It took me a second to realize something was off about what I just saw. When I looked again, I noticed a face looming in these two large trees that are situated on the corner of their house. It wasn’t a familiar face either, it was this perverted crumby looking old man, just hiding in the bushes in broad daylight. I realized 2 things immediately, a) this guy was up to no good ( I know this, being someone who has hid in the bushes many times) and b) I had the opportunity to catch this weirdo and maybe whip his ass (taking the law into my own hands is kind of a fantasy of mine). So, i pointed at him and screamed “Hey you”. He jumped out of the bushes. My neighbor was handing candy out and screamed when she saw this. He sprinted between our houses into the backyard and toward a busy road that runs behind our street. I ran into the garage and grabbed a baseball bat, ran out the side door and chased him down the road, I got so close too! But I failed, he wanted it more than me I guess. The neighbor lady had called the police while this was all happening and they showed up pretty quickly, telling us that this was one of multiple calls they received about a guy creeping in the area.

Ryan Travis Christian, “X2Go2Work!”, Graphite on Paper / Image courtesy of Guerrero Gallery

SC: HA! What a priceless story. Thanks for sharing the background. The suburbs can definitely breed the most absurd happenings. I can see how these personal stories are rich with the content that can fuel your work. I’m also interested in your aesthetics. There is an amazing fragmentation in your work that allows for multiple references to appear simultaneously. It is evident that you absorb a lot from contemporary art and culture and subvert it for you own purpose. I’m curious about the artists that you are interested in right now, the art history that you keep coming back to and in general, things that have been captivating your attention as of late?

RTC: My pleasure, there’s lots more where that came from. I interviewed Ben Jones a long time ago and he said it better than I ever could… “It takes only the most ballin’ original tightest visual shit possible… I want to see fucking mint ass visual shit and then and only then will I approve/steal it”.

Doing the whole blog thing and curating and just looking at a lot of art in general, I’ve developed a very specific taste for elements I think work best, and like any artist, you can look at their work and probably develop a complex diagram of where everything they made came from. It’s constantly changing too. Current artists would include but isn’t limited to: Paper Rad, Marissa Textor, Mike Rea, Bjorn Copeland, Scott and Tyson Reeder, Jose Lerma, Geoffrey Todd Smith, Eddie Martinez, Eric Yahnker, Allison Schulnik, Ben Stone, Deb Sokolow, Cleon Peterson, Ben Stone, Xylor Jane, Andrew Schoultz, Joseph Hart, Chris Duncan, Samantha Bittman, Garth Weiser, Lightning Bolt, Hilary Pecis, Evan Gruzis, Glen Baldridge, Michael Krueger, Chris Johanson, Joe Roberts, Adam Scott, Cory Arcangel, Ann Toebbe, CF, Scott Wolniak, this list could seriously go on forever… Older inspiration comes from; Conlon Nancarrow, Guston, De Kooning, Archibald Motley, Ub Iwerks, Bruce Bickford, The Hairy Who, George Condo, Ray Yoshida, this could go on forever too. More than anything, I ideally want to be able to do for future generations what these people have done for me, which is make me believe that art isn’t totally stupid. If there’s a name you don’t recognize, please google it.

Ryan Travis Christian, “Jailbirds”, Graphite on Paper, 2010 / Image courtesy of Guerrero Gallery

SC: In your current exhibition Sad Sacks at Guerrero Gallery in San Francisco, you have produced an epic-scaled drawing as well as a collaborative work with Chris Duncan. It seems that you are certainly interested in expanding your practice. Beyond furthering your intricate drawings, do you have any projects or exhibitions plans that are outside of your current method of working?

RTC: I’ve been doing the smaller scale/ super tight drawings for a couple years now and I’m going to continue that. But there are a lot of other things that I want to pursue, probably too many. After knocking out that big one @ Guerrero in 2 days (the biggest thing I’ve done thus far), I’m definitely jazzed to be back home in the studio with an extra added energy. Next month I’ll be doing two more massive wall pieces, one with Western Exhibitions at the MDW Fair and the other at the Co-Prosperity Sphere, both here in Chicago. I’ve been dj’ing thematic sets recently with Club Nutz (the worlds smallest comedy club) and will continue to do that as much as possible. Also trying to acquire a full on drum kit to execute some music I’ve had in my head for a minute now. I’ve been juggling around some sculpture/video ideas and also have been attempting to make paintings of my drawings, ideally in 5 years from now I’d like to have the option of taking an idea I have and being able to execute it in any medium, while maintaining a certain caliber. Also developing a hand drawn animation a la’ 1930’s style, which won’t be finished for a long time! Trying to run the gauntlet…

Ryan Travis Christian “Freewheelers”, Graphite on paper / Image courtesy of Guerrero Gallery

Concerning the collaboration with Duncan, that was amazing, but that’s because he’s a force of nature! I’ve been doing collabs for a short amount of time, sometimes they ‘re lemons other times they blow your mind. I think it’s important for like minded artists to collaborate, it’s just another way to communicate/bond/learn from one another, plus it’s a lot of fun. I’ve done some with Eric Yahnker, Alexis Mackenzie, Dana Dart- Mclean and Chris, thus far. I have a nice list of about 15-20 folks that I’ll be working with over the next 6 months, which will culminate in a project space show at Western Exhibitions in October alongside my debut solo show with them. Got a big curatorial project in the mix and a book project based on what could be my gnarliest story ever! Plus a bunch of group shows between now and mid 2012 all over the country and abroad. Keep your eyes peeled for Ryan Wallace‘s upcoming curatorial project based on the idea of “home” that’s coming up in May, it will be a game changer. I signed up for a summer golf league. I feel like when I type all of this shit, I’m begging the cosmos to splatter my face with egg. It’s only a matter of time until you read about my head exploding.