Walead Beshty at Regen Projects

In a former life, Walead Beshty may have rubbed elbows with Patti Smith. Flaunting her contemptuous disregard for the cautionary advice of her peers, Smith famously denounced words as mere “rules and regulations” in her rendition of Van Morrison’s “Gloria.” In one unruly, titillating performance, Smith flipped the good ol’ boys’ fraternity of rock and roll on its ear by lampooning the muffled sexism of the music industry, exposing the frivolous laws that command its economy. In other words, let’s not shy away from the fact that sex sells in this game, kiddo. Similarly, the art world has its own rulebook. And Beshty has a shredder.

The first rule of art market is you do not talk about art market. The vernacular of commodity is strictly verboten, seductive aesthetics are ill-advised, and materiality is secondary to concept. The clandestine, operational logistics of the art world are something of an urban legend—on which Beshty shines an astute light. In a 2009 interview with BOMB Magazine, the artist acknowledged this hush-hush stigma, stating: “Any art effect people don’t like, or find alienating, is ascribed to the market. In this, and in all other aspects of art making, I think transparency is the only way to destabilize the mythologies of the art market, and of art in general.” In his current exhibition at Regen Projects (Los Angeles, CA), PROCESSCOLORFIELD, Beshty takes a wily swipe at the absurdity of the art world’s covertness with more than twenty-five new works, ranging from photograms to readymades to the mulched remains of works “unfit for exhibition.” He deftly navigates the precinct between improvisation and calculation, as well as object and material, while subverting the rules that govern each model.

With a discerning hand, Beshty manipulates the analog qualities of film in his “Black Curl” photogram series. Perhaps a tangential nod to his 2006 “Picture Made by My Hand with the Assistance of Light” works, which were the result of a roll of film’s unintentional exposure to an airport X-ray machine, Beshty’s most recent photograms hypostatize fluke relationships between photo paper and color structures into electrified bands of twilight hues. Austere blocks of black and white border sherbet-colored ribbons of pink and orange, as if we were peeking at the garish Los Angeles sunset through a haphazard set of blinds.

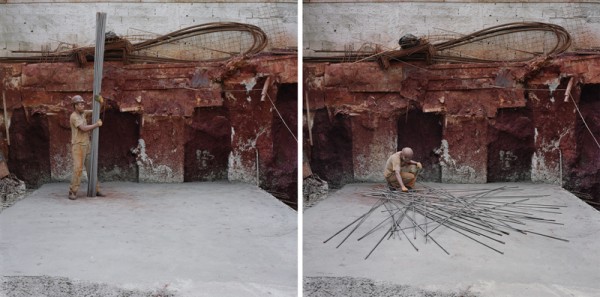

Reflecting the vibrant patterning of the photograms are Beshty’s “Copper Surrogates,” whose polished surfaces are tarnished with alarmingly prevalent fingerprints, smears and coffee mug rings. To the seasoned gallery-goer, the constellation of blemishes on the works’ surface is cause for stifled panic, as art-viewing policy is built upon a longstanding empire of “Don’t Touch.” This is Beshty’s guerrilla erosion of one of art’s most fortified rules. Literally used as workspace for the duration of a prior exhibition, the sullied copper counters display traces of conversations past, meetings adjourned and infrastructures built—empirical evidence that alludes to the presence of the industry, the gallerist and the collector.

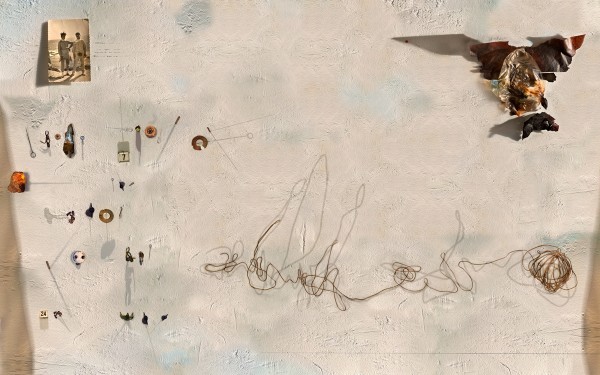

Finally, in a tongue-in-cheek intimation of the sway of institutions, Beshty’s “Selected Works” reframe the notion of artistic failure, unearthing the unseen practice behind the tradition of curating and contextualization. Shredding his self-declared “unsuccessful works,” Beshty turned the refused scraps and slivers of photos and paintings into reconstituted mulch, displaying the literal and conceptual debris of exploratory authorship in an unconventionally candid manifestation. In his forthright acknowledgement of the tensions between the material and the visual, as well as between posturing and actuality, Beshty bends the rules with dexterous maneuvering and a covert smidge of sensory seduction. The art market never saw it coming.

PROCESSCOLORFIELD is on view through May 14, 2011.