“It is so very hard to become a man. . .Everything threatens to beat us down, to strip us of our biological birthright, to destroy us simply for asserting our essential, metaphysical manliness.” – Roger D. Hodge, Onan the Magnificent: The Triumph of the Testicle in Contemporary Art (2000)

Today, Matthew Barney will receive the prestigious Golden Gate Persistence of Vision Award during the San Francisco International Film Festival, a prize whose past winners include filmmaker Errol Morris, Robert Frank and Kenneth Anger. The award recognizes unconventional methods in filmmaking; Barney, who often does away with narrative altogether in his films, is a perfect fit.

The POV award will honor Barney’s ongoing, twenty-four-year-old project, DRAWING RESTRAINT. The earliest incarnations of the series, begun in 1987 when Barney was a twenty-year-old Yale undergrad, feature the young artist alone in his studio. Having set up a several video cameras on tripods to film the action, Barney respectively jumped, reached, and lunged against various self-restraint systems. Holding a homemade drawing tool, Barney pushed against that which that held him back (either a physical blockade or a strapped harness system) in an effort to make a pencil mark on a far wall. The wild, graphic lines left behind on the wall are the evidence of his repeated, near-futile efforts to overcome hindrance.

Matthew Barney, DRAWING RESTRAINT 2 (1998). Documentary photography by Matthew Barney. Copyright Matthew Barney.

This early work was strikingly simple, ambitious, and desperate. The young Barney, who had been a star quarterback throughout high school, tapped an athletic vocabulary that had by then become part of his parasympathetic nervous system. The results—forms generated through the properties of repetition, physicality, and failure—held as true in his studio as they had on the playing field. Part video, part performance, Barney has continued to semi-autobiographically probe the body’s relationship to gravity, strength, architecture and desire.

The DRAWING RESTRAINT series had a profound effect on me, as it continues to have on many. For a long time I considered it to be an inquiry into masculinity, in part because of Barney’s own athletic history (football is supposedly not a sport for girls), not to mention Barney’s use of his own physically fit, distinctively male body. Barney’s heroes— including Richard Serra and former Oakland Raider’s football player Jim Otto, each of whom he has directly employed or referenced in his art—broadcast an aura of testosterone in their own work. Otto, in particular, is famous for his toughness in the face of pain. In fifteen years, he never missed a game, and that includes post- and preseason games and injuries.

Matthew Barney, Video still from DRAWING RESTRAINT 3 (1988). Video by Randolph Huff. Image courtesy of Gladstone Gallery, New York. Copyright Matthew Barney.

As Barney’s stock grew in the art world (exponentially, as it turned out), the artist continued to shape and evolve DRAWING RESTRAINT. While he is best known for his lush, sprawling Cremaster Cycle films (1994–2008), Barney never stopped pushing his earliest series forward. While still minding the original thematic considerations, the last few projects have been more and more complex in narrative and production. The most well-known and ambitious of the series, DRAWING RESTRAINT 9—itself a feature length film starring Barney and his real-life partner Bjork as lovers aboard a Japanese whaling vessel—was released in 2005. Though not all of the later iterations of DRAWING RESTRAINT are as elaborate or expensive as DRAWING RESTRAINT 9, every evolution seems to result in a slicker and more sophisticated product.

All of which leads me to wonder: what happens when underdog athlete triumphs? Do we still root for him? How does his style of play shift with the burden of expectation? Ironically, the market success that allowed Barney the platform and financial backing to expand upon the series is the very force which problematizes its condition; I can’t help but feel that the later work has lost the immediacy and fragile bluntness that made the early work so appealing.

Matthew Barney, DRAWING RESTRAINT 10 (2005). Documentary Photography by Reggi Shiobara. Image courtesy of Schaulager. Copyright Matthew Barney.

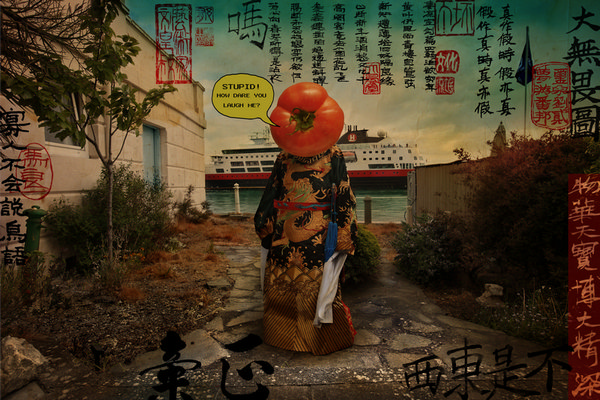

Concurrent with the film festival award, DRAWING RESTRAINT 17, one of Barney’s most recent works, will be screened here in San Francisco in the Kabuki Theater in Japantown. For the first time, he is not the protagonist of the series. Rather, in a split screen projection, a young blonde woman is shown scaling the sharp, modernist edges of the interior walls of the Schaulager Museum in Basel, Switzerland. The action echoes several earlier iterations of the DRAWING RESTRAINT series, in which Barney scaled museum walls (particularly, DRAWING RESTRAINT 11 and 12). This new work also recalls Barney’s video, Blind Perineum (1991), in which the artist scaled the walls of the Barbara Gladstone Gallery in New York, wearing nothing but the harness to secure his climb.

The presence of a female lead prompts new possibilities in Drawing Restraint, or at least, new questions. While Barney’s Cremaster Cycle films are often considered in relation to masculine and feminine differentiation and performance (the title refers directly to the thin muscle which raises and lowers testicles in accordance with temperature, fear, or stimulation), the DRAWING RESTRAINT series is consistently described in terms of a gender-neutral “body” as it confronts resistance in space. The presence of the young, athletic woman in DRAWING RESTRAINT 17 is an unexpected shift, and one that illuminates our refusal to see Barney’s maleness in the first place, at least in the case of the DRAWING RESTRAINT project. Why is it that we notice the implications of gender only when a female is the body is in question, and how do the stakes of the project change along with the sex of its protagonist? Whether or not Barney deliberately calls this issue into question with his use of a female heroine is almost beside the point. The choice cannot, and should not, go overlooked; just like that, a series that has recently risked becoming formulaic awakens to change.

Matthew Barney, DRAWING RESTRAINT 17 (2011). Photograph by Hugh Glendinning. Image courtesy of Gladstone Gallery, New York. Copyright Matthew Barney.

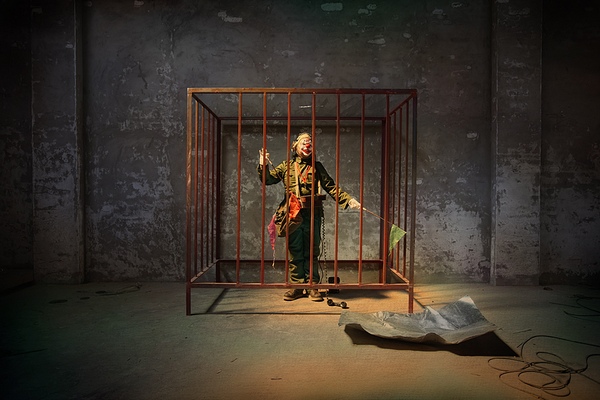

Rob Pruitt, tbc, 2010 (detail)

Rob Pruitt, tbc, 2010 (detail)