Ulla von Brandenburg

Ulla von Brandenburg, Chorspiel, 2010. Black and white video on a blue-ray DVD, audio 10 min 35 sec. Courtesy of the artist and art: concept, Paris

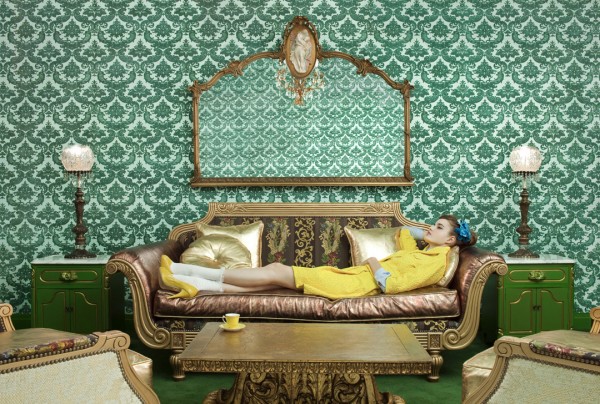

‘Neue Alte Welt’ (New Old World), an exhibition of Ulla von Brandenburg’s recent works, is on view at The Common Guild, Glasgow till 21 May 2011. Presented across two levels, the exhibition proceeds as a journey where one seems to travel from the perspective of an audience and performer, before entering the backstage.

The first room features Chorspiel, a black and white film set in a field amidst a forest, where a family of three generations encounters a wanderer. The weight of the scene unfolds across three acts in this operatic production, written and composed by von Brandenburg, with a Greek chorus of fifteen singers echoing and voicing the characters’ psychological states and proffering a predicament to the audience concerning the characters’ circumstances and uncertain future. References to Ingmar Bergman shape our reading of this predicament as an existential one, tinged with longing and anticipation, and amplified by the unrevealed contents of the box that the wanderer bears.

Ulla von Brandenburg, Theatre, 2011. Wall painting, Dimensions variable. Installation at The Common Guild, Glasgow. Courtesy of the artist and art: concept, Paris. Photo by Kendall Koppe

The emotions and distance vis-à-vis the actors on screen take a turn on exiting the room, where we encounter a floor-to-ceiling painting depicting a grand hall filled with audiences. Ascending the circular stairway creates the sense of being thrust onto a stage with the spotlight reflected in an orange hue, accompanied by the strains of Chorspiel which seem to now function as the orchestra for Theatre.

L-R: Mephisto 2010, Sunburnt fabric, small wooden hoop, 255 x 150 cm; Angel 2010, Sunburnt fabric, fishing-rod in three parts, 255 x 150 cm; Krawatten, abgeschnitten, 2010, Cut-up ties, Dimensions variable. All works by Ulla von Brandenburg, Installation at The Common Guild, Glasgow, Courtesy of the artist and art: concept, Paris. Photo by Kendall Koppe

The performance ceases upon entering the second room, past Krawatten, abgeschimitten, a drape composed of colorful ties affixed to a doorframe, demarcating another realm. The objects here assume evocative material traces of Chorspiel, from Schachtel (box) recalling the mysterious box brought by the wanderer, and the shining sun as sung by the wanderer, having an enduring effect on Angel and Mephisto. Though the associations with Chorspiel linger, the features of these objects, including their folds, patterns and etchings, distinguish them as props with a life of their own, possessing their own histories and awaiting further deployment.

Ulla von Brandenburg, Schachtel, 2010 (box). Cardboard box rolled-up ribbons. Installation at The Common Guild, Glasgow. Courtesy of the artist and art: concept, Paris. Photo by Kendall Koppe

Though working through the histories and formalities of theatre, von Brandenburg’s works venture beyond notions about the theatricality of life. In this new old world, history becomes the filter for one to live in the present; a journey of apprehension, hope, glory and contemplation.