Bruce Nauman, Going Around the Corner Piece, 1970, © Coll. Centre Pompidou. Photo: Georges Meguerditchian

In the self-explanatory show entitled Video, an Art, a History 1965 – 2010, the history and evolution of the video art genre are recounted through 50 video works and installations, drawn from the collections of both the Singapore Art Museum and Centre Pompidou. Having developed in tandem with the apparatus of television and the analogue and then digital video cameras, video art’s reconfiguration of the politics of image-making and its ability to place the spectator as an indispensable agent in a work’s existence are significant tenets on which the exhibition is established. The infinitely widening scope and scale for the production and interpretation of (moving) images, the mode of their dissemination, and the documentation of performances (technical or otherwise), pose several key but general questions around which the works are grouped.

The pertinence of such questions however, falters in the collaborative effort that has shown up more differences than similarities. Reconciling the inventory of the Singapore Art Museum with the Centre Pompidou’s reveals the tentative forays into the processes of historicisation that are only beginning to develop in Southeast Asia and the inevitable rift in the standpoints of Western art and Southeast Asian art history. The Pompidou’s international collection stretches back 4 decades to the genesis of video art; the Singapore Art Museum’s inventory spans approximately a decade that really began with the Asian Financial Crisis (1997-8) and is focused on works produced in the surrounding geographical region. The wider ramifications of this collaboration go beyond an overwhelming inventory imbalance and the expanded visual vocabulary that video technology provides; indeed the emerging ideological differences become apparent when speculative comparison – the attempt at a comparative video-art history, should it even exist – inevitably sets in.

Pipilotti Rist, A la belle étoile (Under the Sky), 2007, © Coll. Centre Pompidou. Photo: Georges Meguerditchian.

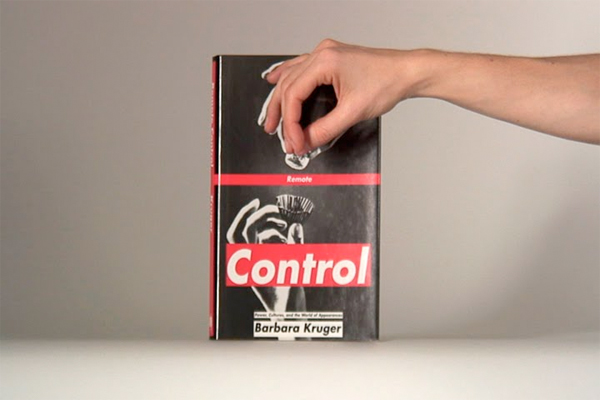

The seeming futile effort of historicising video art in this instance, is thus mitigated by several thematic (and loosely chronological) focuses that ground the show: television critique, the representations of self, the documentation of performance, installation in space, landscape as metaphor, video-as fiction and the deconstruction of narratives.

If early efforts by video pioneers such as Nam June Paik, Bruce Nauman and David Hall took the definition of an art object beyond its conventional parameters as a static entity produced for visual consumption, perhaps the greatest strength of video art triumphed in this show is the unprecedented potential of experiential interactivity between artist, installation and spectator. Peter Campus’ Interface (1972) invites the viewer to superimpose their reflection onto their projected image after which they simultaneously face 2 images of themselves – one of the video image and their reflection on the glass screen. The inherent sense of ego coupled with a measure of curiosity is a potent brew, particularly when facets of the multi-layered self are revealed in art. Like the literary Doppelgänger (the ghostly and sinister double), artists’ early efforts recognised the potential of video art in exploring the loss of existential reference in which the traditionally held view of the consecrated sense of self is destabilised. In Bruce Nauman’s Going around the Corner Piece (1972), the surveillance set-up is symmetrical and simple: perched in the corners in a white square-room are closed-circuit cameras and small TV monitors that capture visitor movements going around the corner of the enclosed space. The spectator’s image disappears from view as he/she rounds a corner; speeding up in an attempt to play catch-up with one’s image results in a unsuccessful tail-chasing endeavour – which is probably the glorious core and yet most vexing part of this work.

Peter Campus, Interface, 1972.

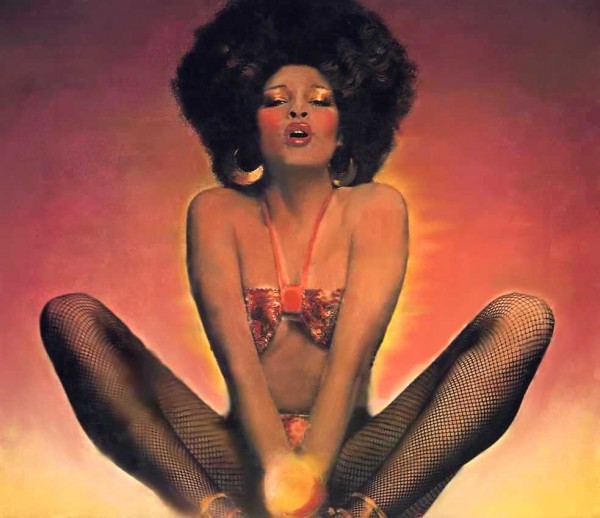

Departing from the investigative preoccupation with the apparatus and the monolithic hold that television had, video art had, by the 1980s, begun deconstructive strategies of memory and narratives, debunking on its way, stereotypes of sexuality, ethnicity and gender perpetuated by the very same mode. Nam June Paik’s semi-documentary Guadalcanal Requiem (1979) explores the subjectivity of memory through the deconstruction and subsequent reconstruction of narratives, in a film that coalesces history, time, cultural memory and mythology on the site of one of World War II’s most devastating battles in the Solomon Islands. Surrealistic images of archival footage, interviews, Charlotte Moorman’s fragmented cello performances come together like a scratchy Hitchcock–Buñuel/Dali crossover. The haunting collage is often fraught with poignant tension and a sense of the macabre: interviewees with singular (or paltry) memories picking up where some have left off; Moorman playing a cello with a long palm leaf against a thunderous horizon, and at another time, performs concealed in a body bag.

Guadalcanal Requiem, Nam June Paik, 1979, © Nam June Paik Estate video still Courtesy Electronic Arts Intermix (EIA) New York

A deconstructive approach to the moving image seemed to be video art’s trajectory from the 1990s into the early 21st century, incorporating new developments of photo processing, digital editing and image layering in contemporary visual culture. Swiss conceptual artist Pipilotti Rist’s A la belle étoile (2007) moves between micro- and macrocosms on horizontal and vertical surfaces. As suggested by curator Christine Van Assche, such works operate on removing depth of field, redefining in the process, the spectator’s own rapport with space.

Despite the influence of the commercial mainstream, video art has nevertheless, retained its earlier forms: the performance documentary, mixed-media texts, or even the visual portrait. Such forms seem conceivably better suited to the preoccupation with art’s social purpose and its context of production that remain dominant traits in Asian-produced videos; perhaps most similar to the historical Western notions where art was produced within corresponding socio-political backgrounds. Just as Gustav Courbet’s post-romanticism was a rejection of academic and bourgeois juste milieu, much of Southeast Asian works are filled with the rhetoric of social change in which media artists show no desire to be unbound from their local cultural matrices. By continuing to invoke ties to tradition, incredibly varied configurations (or even fragments) of history that appear in Asian works at best, seem to read as disjointed narratives to the viewer unschooled in the intricacies of China’s tumultuous last few decades.

Yang Fudong, Backyard - Hey! Sun is rising, 2001.

Yang Fudong’s Backyard – Hey! Sun is Rising (2001) follows the Keatonesque slapstick antics of four young men enacting military rituals and traipsing around with swords, questioning the meaning of rituals in the wake of social changes. A richer meaning however, could be gleaned from Yang’s work if considered in the light of the communism’s wane, as well as in the historical traditions of Zen, martial arts and the aesthetic disciplines of poetry, painting and calligraphy – all of which are mirrored in aesthetic form and content in his videos. Like Yang’s disoriented characters who seem to seek penance in an environment marked by repression, The Propeller Group’s Uh… (2007) confronts Vietnam’s youth culture’s adaptations to the changing socio-cultural and political landscape through the symbolic use of graffiti, and the disorder and spontaneity it represents – the antithesis of Vietnam’s ordered socialist state.

Uh..., The Propeller Group, 2007, Singapore Art Museum Collection

Manet's Luncheon on the Grass and the Thai farmers, Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook, Two Planets series, 2008, Singapore Art Museum collection

While Western artists like Pierre Huyghe and Issac Julien integrated mixed media installations with the spectacular and immersive experience of cinema, Asian filmmakers also tended to persist with the use of narrative (and at times, the meta-narrative) as a didactic strategy. In Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s The Two Planets Series (2008), Thai farmers – groups of people blithely oblivious to the cultural or economic baggage associated with canonical works of Western art history – talk about several cornerstones of modern European painting. Their discussions of Manet’s The Luncheon on the Grass (1863), van Gogh’s The Siesta (1889-90) and Millet’s The Gleaners (1857) are artlessly literal, context-less and extremely humourous, with the constant comical tendency to drift towards off-topic situations. Straddling the diverse worlds of rural farming and art history, Rasdjarmrearnsook raises questions of socio-cultural context, the parameters of interpretation and appreciation, but stops short of suggesting that our efforts in basting together a coherent narrative and interpretation of art are vain but significant detractors from the lost pleasure of looking.

********

Video, an Art, a History 1965 – 2010 is presented by the Singapore Art Museum and the Centre Pompidou, and runs through 18 September 2011.