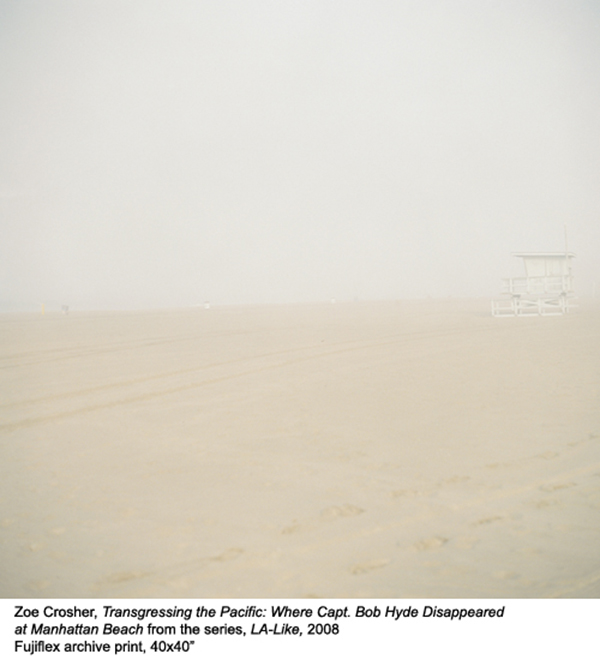

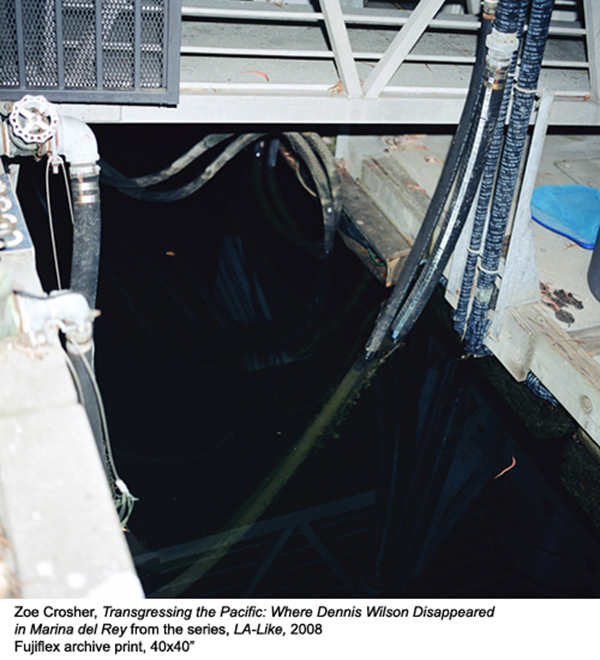

Zoe Crosher’s haunting photographs—showcasing spots where both fictional and non-fictional characters disappeared—have been on display for the last month at Las Cienegas Projects in Los Angeles. The show closes July 16th. Crosher recently sat down with DS writer Carmen Winant to talk about the project and her work in general.

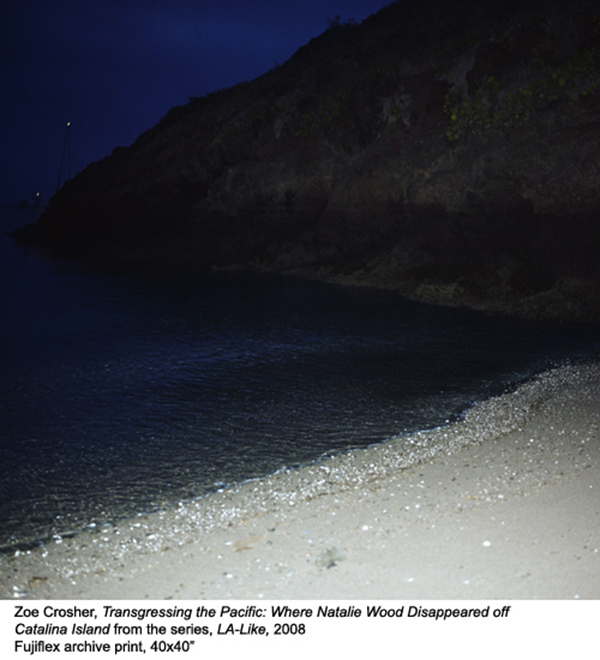

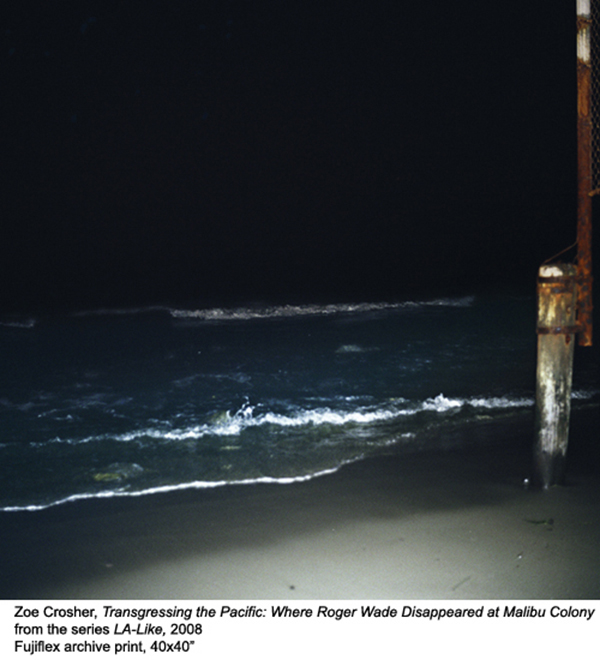

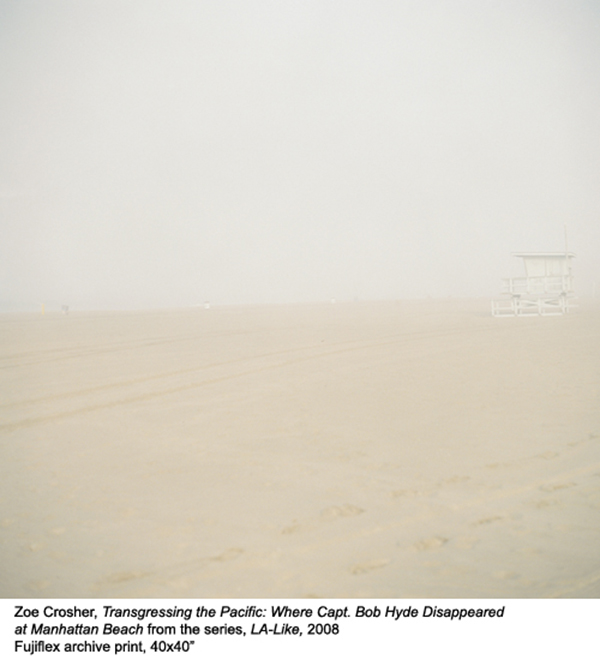

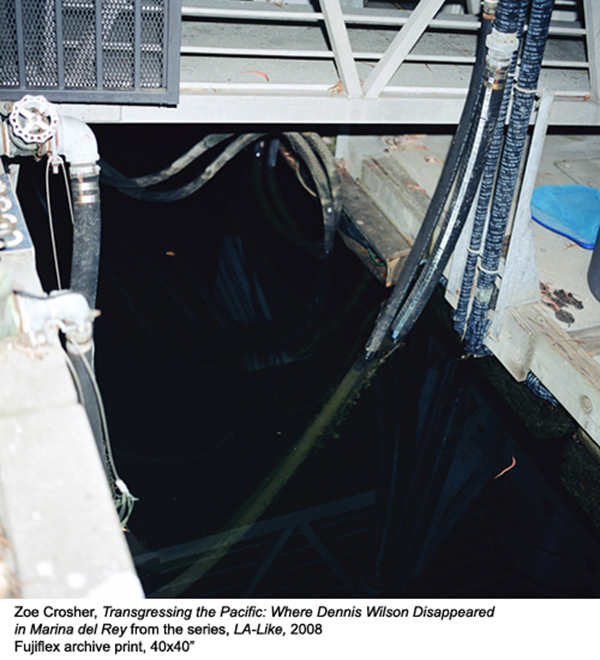

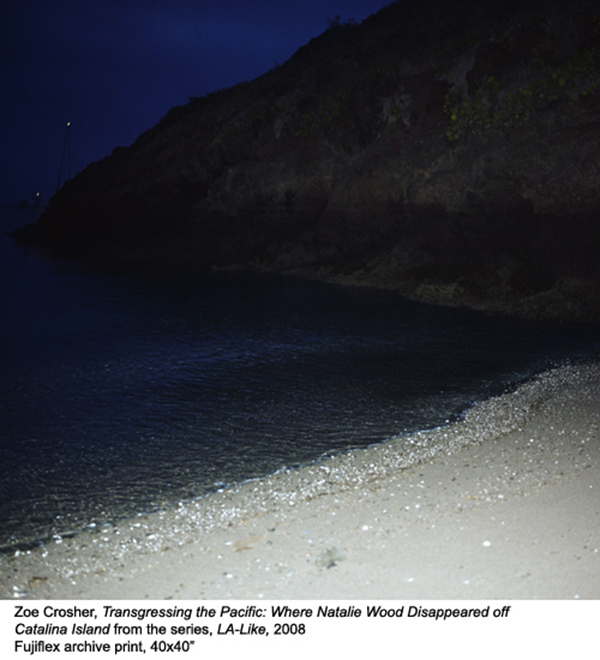

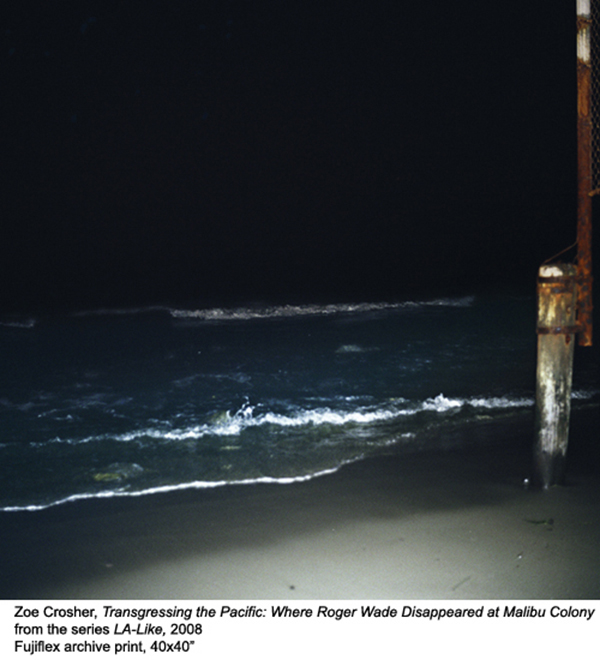

Carmen Winant: Hi Zoe! Thanks for agreeing to talk with us. In your latest series, LA-Like: Transgressing the Pacific, you photograph real and fictional sites of disappearances into the Pacific Ocean. With descriptive titles like Where Natalie Wood Disappeared off Catalina Island, there is no distinction made between historical figures and invented ones. For instance, you document the Marina Del Rey site where the Beach Boys’ Dennis Wilson really died in 1983, alongside the location where John Voight’s character drowns himself in the 1978 film Coming Home. Can you address the choice to include real and unreal figures in the series?

Zoe Crosher: Yes. My practice deals with photograph as a tool of fiction of documentary. I have long been interested in thinking through the ways that memory operates through photographs on the basis of the stories that we ourselves write. Also, Los Angeles has a unique and specific relationship to fiction—truth and imagination are easily conflated here—so I am particularly interested how I can use documentary photography to the same end. Ultimately, no matter how adept we have become in reading photographs, there is still the traditional assumption of an overarching “truth” in our approach to documentary work, which I hope to complicate.

CW: I’m drawn to this notion of departures, of heading west to find one’s destiny—and when that cannot hold, even further west—into the ocean’s depths, as the case may be. There is something so tragic and poetic about the idea that the border of the coast cannot hold you. I saw that you wrote about the conundrum of Manifest Destiny: “the endless promise for once you reach that unreachable place, and then you have arrived, there is no where to go anymore.” There is something so fundamentally lonely about that. Can you address this idea of containment, of reaching forever farther, even if it means one’s own demise?

CW: I’m drawn to this notion of departures, of heading west to find one’s destiny—and when that cannot hold, even further west—into the ocean’s depths, as the case may be. There is something so tragic and poetic about the idea that the border of the coast cannot hold you. I saw that you wrote about the conundrum of Manifest Destiny: “the endless promise for once you reach that unreachable place, and then you have arrived, there is no where to go anymore.” There is something so fundamentally lonely about that. Can you address this idea of containment, of reaching forever farther, even if it means one’s own demise?

ZC: All my work certainly has a darker backdrop, a kind of impossibility of knowing, but I never look at the work as being lonely. It has cathartic potential, perhaps. And it certainly is concerned with trauma. Joan Didion addresses this sense of Manifest Destiny so well in her books and essays, as a schism between a promise of something and what it actually may turn out to be.

The lore of moving west—what happens when you hit the border or reach the shore, when you can’t push any further—this is a very loaded threshold. Even Lewis and Clark couldn’t believe it when they hit the Pacific, as if the continent should in fact be never-ending, endlessly unfolding. If you live in LA, a frequent question is, “Where are you from?” It implies, of course, that no one is really from here, that the city holds those that sought it out.

CW: You use a medium format camera, which I tend to think of as a nostalgic and self-contained format.

ZC: I’ve always shot with a square format. The square complicates presumed ways of looking. When I started photography seriously in college, I was immediately trying to interrupt what was presumed “real.” For this project I used a Bronica camera, and a tripod and a flash when shooting at night. I only shot film. The final photos are printed on Fujiflex paper, which has a very glossy, reflective surface. In the gallery they are hung fairly low, creating a sense of falling into the water.

CW: How much research went into uncovering the spots where these people disappeared? Or are these locations their own fictions?

ZC: The research took many forms. I had a great intern working with me—Jason Underhill—and together we did newspaper research, looked at police reports, and watched the movies over and over. We found three different articles about Natalie Wood’s death in the Pacific in 1981, but only one mentioned that she was wearing a red down jacket. These selective details are exactly what I am interested in, how we choose to selectively document the past. Some of these places no longer exist; Aimee Semple McPherson faked her own disappearance at the Ocean Park pier, which was halfway between Venice and Santa Monica, and is no longer standing. The final scene for the film Coming Home was in Manhattan Beach, but it was a fantastic goose chase to find the spot, which I originally believed to be in San Diego. There were other issues: The Long Goodbye was shot on Robert Altman’s private property at Malibu Colony, and so on.

Ultimately, this is the point. It was a project that relied on and tested the mimicry of my own memory. History is all estimations, which is effectively a major component of my work.

CW: My next question is about the paradox of marking the SPOT of a disappearance. It strikes me that the idea of being “disappeared” implies that the person vanishes without a trace…do you feel that in some way marking the location lends a certain gravity, much like a gravestone might, to an otherwise mythical action?

ZC: I don’t think it detracts from the disappearances themselves, which, as I mentioned, are still very much my interpretation. I am inspired by crime scene photography, but I can only photograph the moment of crossing, not its finality.

There is something to be said for marking that which refuses be marked. I have been trying to figure out a way to photograph the Santa Ana winds. This idea is so interesting to me—not the expectation of failure, but the expectation of impossibility.

The truth is that everything—every body and every event—is located in space. This process of insisting on a moment that did happen and has a physical reality, the insistence of being a witness, is very important to my practice.

CW: I am interested in discussing this series in light of some of your other LA-Like series, specifically, LA-Like: The Pools I Shot Series and the Michelle duBois project. They both seem tied to place and perception, and the qualities of surface. Can you discuss the relationship between them, perhaps beginning with your interest in water? And, in regards to the duBois series, a kind of desperation to document oneself for consumption by others, and in doing so, creating a kind of vacuum of self?

ZC: Again, all of the work is concerned with testing the limits and constructs of the documentary. The Michelle duBois project is ultimately about the possibility of not knowing oneself—she pretends to be so many versions of herself, taking thousands of photos, all in which she emulates a different persona. She is creating her own kind of destiny in a way, a life constructed on impossible fantasy.

LA-Like: The Pools I Shot is a kind of mapping; LA is, of course, tied up with the history of water. I wanted to merge the poetics and the medium. I took pictures of the sun reflecting in pools, and slightly burned the photographic paper in the printing process.

CW: I noticed that the press release for your show includes a quote from Joan Didion’s Slouching Towards Bethlehem. This struck me as a really apt literary source for your work, as Didion so persuasively investigated the profound emptiness and power of celebrity. I was also reminded of her looking at your swimming pool series, specifically her line from The White Album: “A pool is, for many of us in the West, a symbol not of affluence but of order, of control over the uncontrollable. A pool is water, made available and useful, and is, as such, infinitely soothing to the western eye”. And beyond that, Didion’s interest in probing the qualities of mourning, or grappling with disappearance. Have you read much by her? Cinema has obviously influenced your work, but does literature do the same?

ZC: I have read almost every book Joan Didion has every written, and I consider her a great influence on my work. Didion did for writing what I am interested in doing for photography. She collapsed fiction and documentary, confusing the terms of reception and context to great effect. She was a journalist who questioned the very structure of journalism, which ultimately was inextricable for her own reportage. I am working on a book of the entire LA-Like series, and I would love for her to write the introduction.

Didion also encapsulates a version of 1960s California. She’s about my dad’s age, and they both attended Berkeley. So, her work also resonates personally with me; it feels familiar. Didion describes a California that I remember as a child but that no longer exists. Or at least, I think it existed.