This Sunday, From the DS Archives features Ed Ruscha and Marcel Duchamp in the essay “A Shovel, A Roulette Wheel and a Check Walk into A Bar” by Andrew Tosiello.

The following article was originally published on November 22, 2010.

I have a really hard time living in the present. I’m at odds, generally, to be here, now and that fucks me up pretty much all of the time. When I write, especially for public consumption, I anticipate the criticisms and counter-arguments that will prove me a fool and it becomes hard to start working. When I’m at my desk, trying to schedule trucks, I think of where else I’d like to be and how it will feel when I get there (someday, I sigh, wistfully) and then making bills of lading bums me out. Clearly, not living in the moment causes me pain. Duh. So, yeah, I’m working on it.

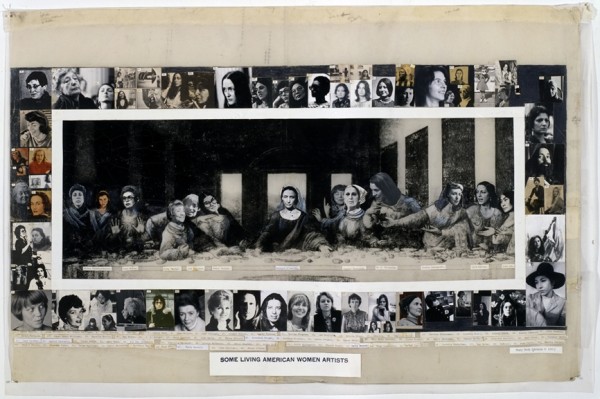

Ed Ruscha, I Think I’ll..., 1983.

“Presentness is grace,” Michael Fried wrote at the end of Art and Objecthood, his damning critique of Minimalism. It’s a strange moment in the essay and I can’t even begin to properly understand it, let alone explain it and I won’t try. I point it out because it has stuck with me since I first read it in graduate school and I wonder about it. A lot. I agree with him as it pertains to living, presentness is grace, an undeserved and great gift, but how does it relate to art? I mean, should art be present in the same way I should be; should it exist as I should try to live?

This is a central question for me, especially when I make art. How much of my work should reflect who I am and how I try to behave in the world? I’ve wondered this since a friend of mine in undergrad pointed out that I’m a funny guy (believe me on this point, please), but that my paintings were desperately serious. “Ugh, the horrors of war!” he said. “Man, where are the jokes?” He was right. I needed to lighten up. It was an important lesson for me. I can’t be one way in the world and make art that denies that experience. Still, does everything have to relate one-to-one to life? Should my work be a direct expression of my beliefs, experiences and way of life?

I’ve been told that if I want to know what I really believe, I should look in my life. If I say I believe in harmony, but there is only chaos in my life, then, well, I really trust in chaos, don’t I? This principle comes in handy, as I find it impossible to think my way out of these types of questions. So, when I want to know what I believe about art, I have to consider art that I really love and really think about. Which brings me to Marcel Duchamp.

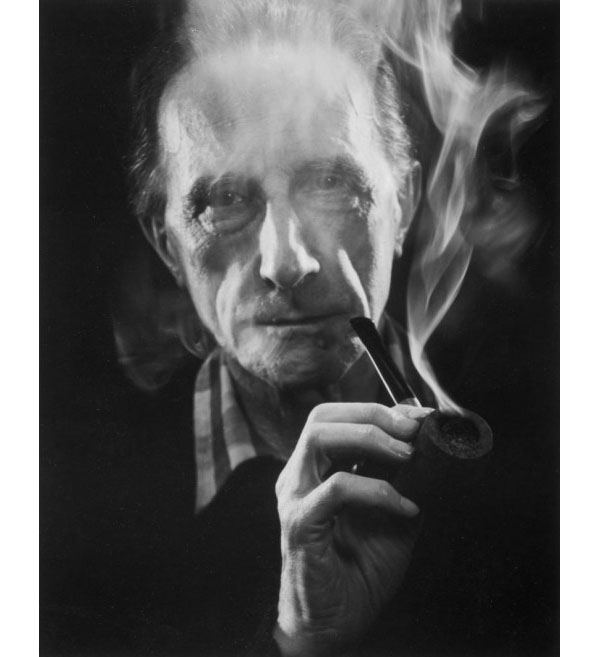

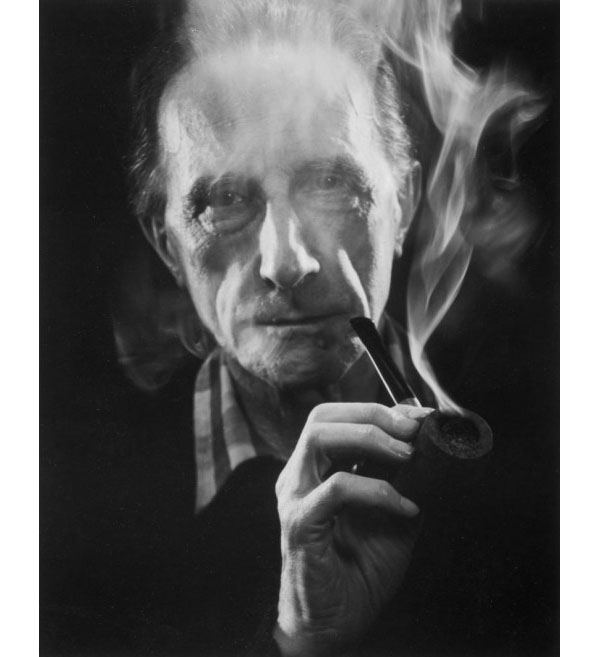

Marcel Duchamp (With Pipe), 1957. John D. Schiff.

When I think about Duchamp I can’t help but be impressed by how damn smart he was. That’s clear, when you consider his development of the readymade and how it reveals the function of the viewer (or institution) in determining an artwork’s status as such. But what really bowls me over, what really kills me, is his ability to let the work unfold, in short, his timing.

So much of his art works on multiple levels all at once, with layers of humor, philosophy, linguistic play and autobiography inextricably mixed, so that the sum is greater than the parts. With in it all, I’m suggesting, is an extraordinary sense of timing. I mean timing both in the sense of being able to tell a joke, but also that his works contain a temporal play, in which they must be experienced through time. That they anticipate meaning accruing to them or being revealed…eventually.

Marcel Duchamp, In Advance of the Broken Arm, 1915

In Advance of the Broken Arm, 1915, was Duchamp’s first readymade, a snow shovel as a work of art, it bore its name, Duchamp’s signature and the year of its designation as a work of art. It’s pretty straightforward, really. It’s a serious work that masquerades as a dumb joke. The act of nomination in the work changed the understanding of what an artwork was or could be and that’s not funny business; it’s deadly serious. The theme of the work, though, is the joke that the shovel is seen not for what it is (an object), but what it will do. Right now, it’s a thing, but later it will have meaning, due to its effect. Someday, we’ll see it not as a thing, but the thing that did that thing. So, is it present?

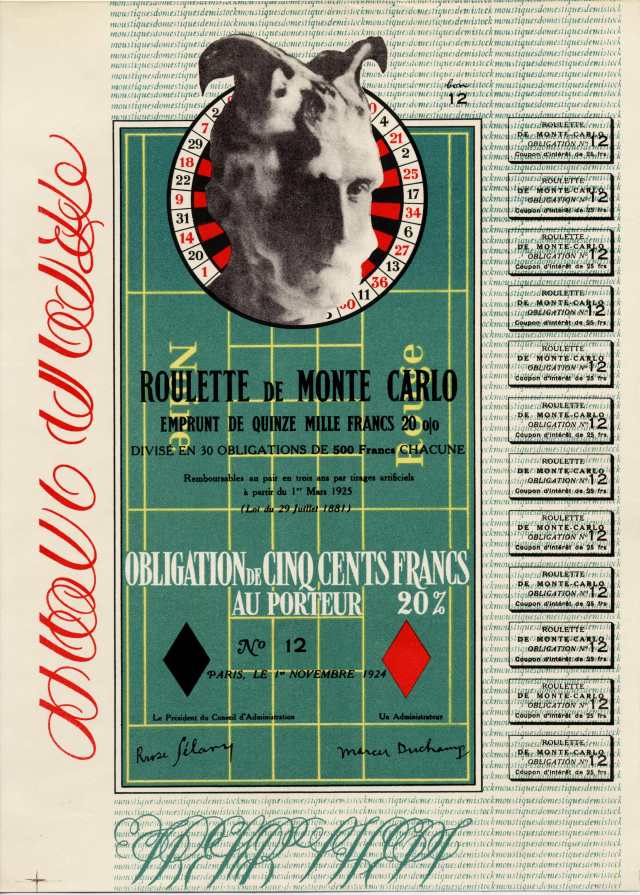

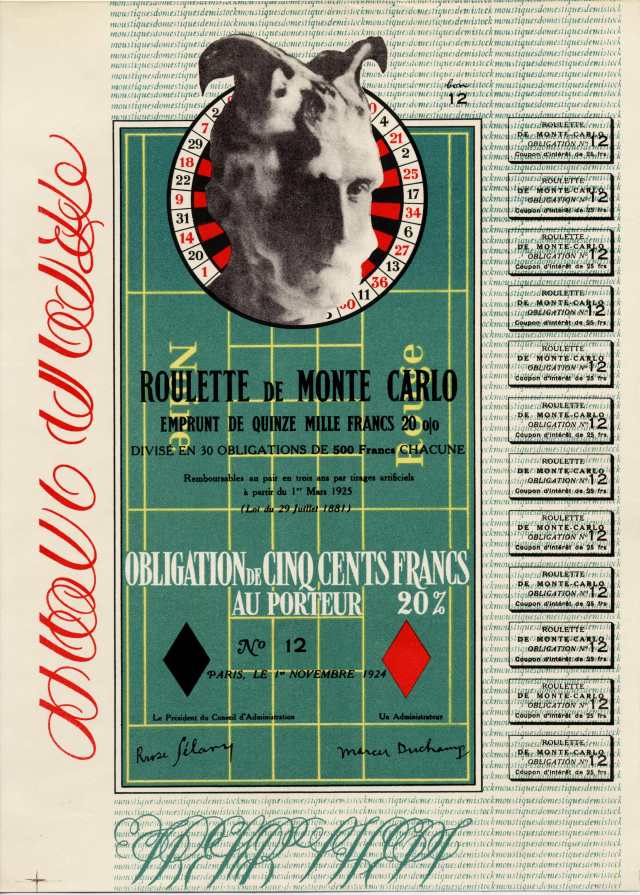

Marcel Duchamp, Monte Carlo Bond, 1924.

In 1924, Duchamp produced the Monte Carlo Bond, an editioned work (only eight were made, but thirty were proposed) to raise funds for a trip to the roulette tables in Monte Carlo. Duchamp’s intended purpose was to break the bank, there, using a system of play that he had devised. This work in its embodied state was really about something else, something in the future. Though it existed in the hands of its purchaser, it was nothing more than a sign of some future possibility. Additionally, the piece, being about roulette, calls to mind the game itself and, particularly, sense of anticipation. Every bet is a potential winner, until the ball stops on a number. While the ball is in motion, anything is possible and the future is held out as a hope.

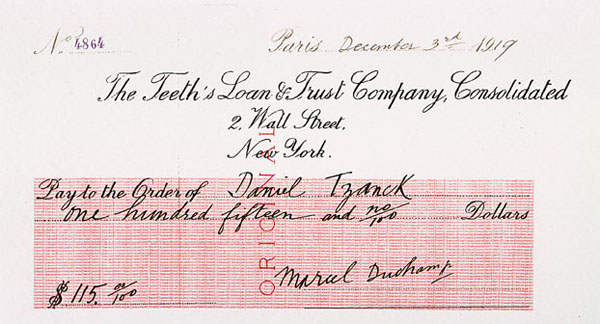

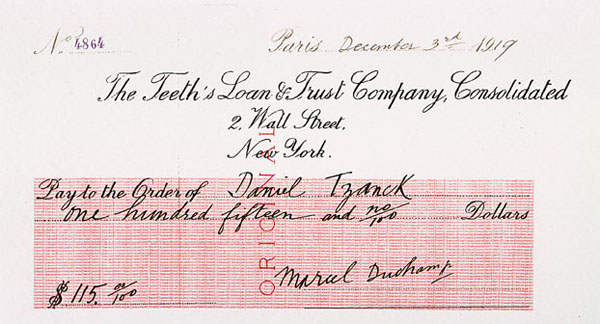

Marcel Duchamp, Tzanck Check, 1919.

Tzanck Check was a work (or was it?) Duchamp made in 1919 to pay for some dental work he couldn’t afford. A large, hand-lettered version of a check made by Duchamp and made out to his dentist, Dr. Daniel Tzanck, for $115, it engages in a play between the real and the fictional. In a sense, it was a real check standing in for $115. In another, it was an artwork, potentially, worth far more. As a real check its value is determined by its present context. As an artwork its value, like a bet at the roulette table, could be far more, but only in the future. So there’s a play between now and soon in effect, too. Finally, as an aside, really, I wonder if Duchamp chose Dr. Tzanck as his dentist, so that he could make this check out to him and employ a sly pun on the word “thanks.” Of course, I may be retroactively attributing this linguistic genius to him, but, then, doesn’t his work suggest this type of slippage in time, anyway?

Thinking about these works has helped me to develop my own sense of how artworks should exist in the world. Certainly, an object, a real one, must (and will, necessarily) have a presence in the present, but, for me, it comes alive, when it can and must develop meanings through time. To boil it down Michael Fried is right: presentness is grace, but existing in time, that’s living.