Unweaving the Rainbow: An Interview with Mike Womack

Colorado-based artist Mike Womack’s show Spectres, Phantoms, and Poltergeists opened at the Chelsea gallery ZieherSmith on September 15. DailyServing’s Carmen Winant had a chance to catch up with him this weekend to chat about his practice and the new work.

Carmen Winant: What is your background in fine arts? Are you trained in sculpture and is that how you would define your practice?

Mike Womack: I’m trained as a painter. In fact, I didn’t start making objects until after graduate school at Pratt. And I currently teach at the University of Colorado in the painting and drawing department. So, I would say: using the vernacular of painting, I make sculpture, installation art, and work within digital media. Above all, I am interested in creating the circumstances and contexts to look at images.

CW: The work seems to engage a certain tenderness, or even magic, with the modern machine and its capabilities. I think the darkness of the gallery and the sound of the motor add to this romance. Can you speak a little bit about your interest in using motorized systems in your work, or I should say, as the subject of your work?

MW: My interests in creating mechanized imagery are definitely sentimental. I have been accused of being a willful romantic, and I must admit, that is really dead on. I’m fascinated with how technology constitutes imagery. I am idealistic – I want to fall for ideas, to be romanced by them in spite of knowing better. But there is a unavoidable complication within the interplay of technology and phenomenology of media; I am at once in awe of technology, and at the same time made to feel curious and suspicious of it. In this way, I am of two minds: I look at my iPhone and think it’s a miracle. But in the same moment, I want to take it apart, interrogate and look at it from multiple perspectives – to understand, technologically and philosophically, just how we have evolved to this point.

Another example of this divide can also be found in the exploded diagram of how to construct an IKEA couch. You don’t need to know much to understand its mechanics. But suddenly there is a shift into a vastly different kind of technology that surrounds us, like, for instance, electrons moving though silicon products (like a vacuum tube), which rapidly becomes harder to grasp. There is a kind of slippage between the late industrial revolution’s innovations and forms in building to the digital age. The space between the two is my interest; I usually have one foot in the mechanized world – making things with prescribed naivety – and one foot in trying to tackle more complex things and how they function.

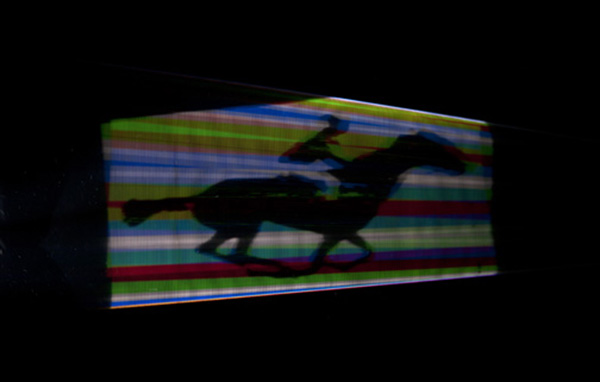

CW: The ways that your work often makes kinetic energy visible through light strikes me as really photographic – which is partially why I asked you about your training and background. Your choice to use Eadweard Muybridge images in the Spectre series also made me more curious about your interest in referencing photography.

MW: I am less interested in the history of photography and more interested in the where the camera aligns and misaligns itself with how we see. I don’t take photographs for my work, but I will often look through the camera lens to see how the values will translate, and how the camera unravels light and creates aberrations.

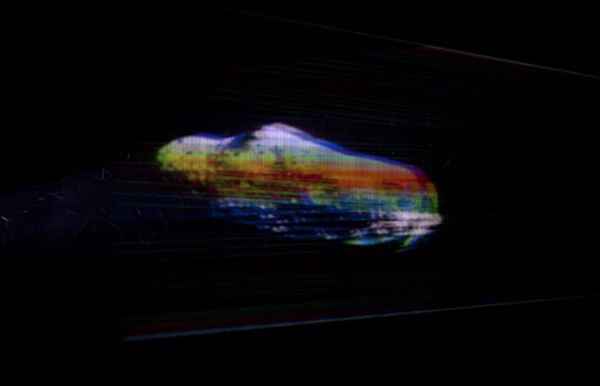

For the Spectre series, I used black and white moving images to make them into the opposite: color stills. This was really the reason I went back to the very first “moving” image (which never had color to begin with) to attempt to reconstitute the image by applying contemporary filters to it, to both unravel and enhance it. I was also drawn to the early Muybridge images as they were taken with late industrial era technologies, which I keep returning to, and which reference a certain nostalgia.

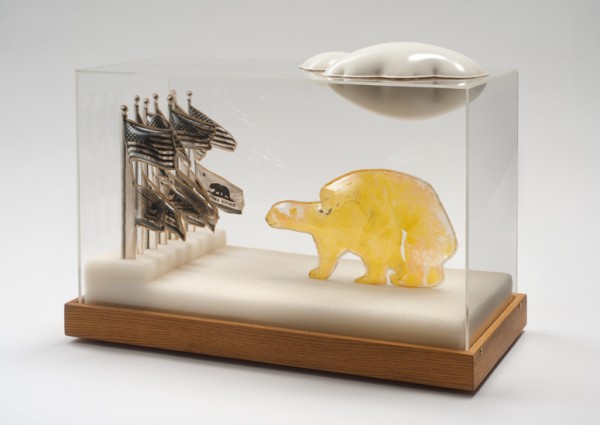

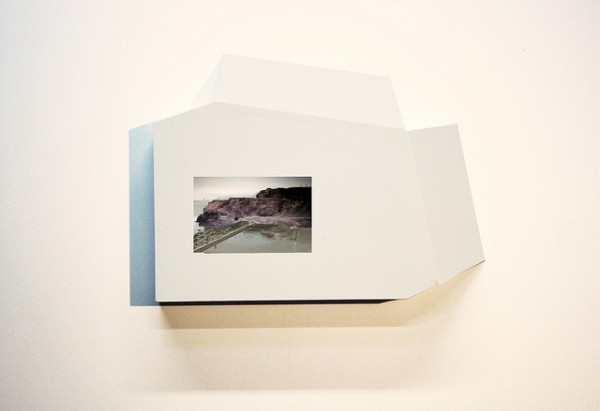

Installation Shot from Mike Womack's Spectres, Phantoms and Poltergeists. Photo courtesy of ZieherSmith.

CW: Have you read John Keats‘ assertion that Isaac Newton was ‘unweaving the rainbow’ in his studies to understand light? In Lamia, Keats wrote, “Philosophy will clip an angel’s wings.” Your own work literally unravels the RGB matrix. Do you relate to Keats’ idea? A fundamental conflict between art and science in experiencing the world?

MW: The final stanza in Walt Whitman’s volume Leaves of Grass speaks to this polemic: “The spectacle of looking at a morning glory at my window satisfies me more than the metaphysics of books.” I’m interested in Whitman for this reason, and have investigated him in this show. I’m fascinated by these conflictual approaches in seeing; of course, there is beauty in knowledge, but must we unravel every natural mystery, and do we dilute them in the process?

To return to Whitman: my piece Threshold at the front of the show is very much about this considered, complicated act of looking. Whitman was a humanist, an advocate for tearing down intellectualism in the arts in favor of a phenomenological experience of the nature world. Looking, for Whitman, was chief over ideas. The piece is comprised of a bluestone taken from the stoop in front of Whitman’s former Brooklyn home displayed simply on a low, wooden table; it has been transformed into a piece of art by its displacement. In becoming conceptual art, Threshold questions and undermines Whitman’s very principles, demonstrative of a kind of contained, internal conflict that runs throughout the show.

The blue screen piece is a good example of this, too. It is meant to emulate the blue screen of a television set that isn’t getting reception (static no longer exists, as there is now no transmission). In addition to creating a surface of both transmitted and reflected light, I also wanted to reference monochromatic painting. I made the piece on aluminum and then coated the paint with industrial grade reflective beads, used on top of the painted road dividers to cause a reflection when hit with head beams. The result is a halo-inducing color field stuck somewhere between Yves Klein blue and Derek Jarman’s 1993 monochromatic film “Blue”. In making this giant, undulating sculpture, I am caught in this struggle between the experience of looking – both suspicious of, and appreciative toward, its potential.

This is the hardest I’ve ever made my viewers look at my work, the nearest to abstraction, the least demonstrative. Ultimately, everything in that show is about the act of looking.

Spectres, Phantoms, and Poltergeists is on display at ZieherSmith from September 15 through October 15.