Betye Saar at Roberts and Tilton

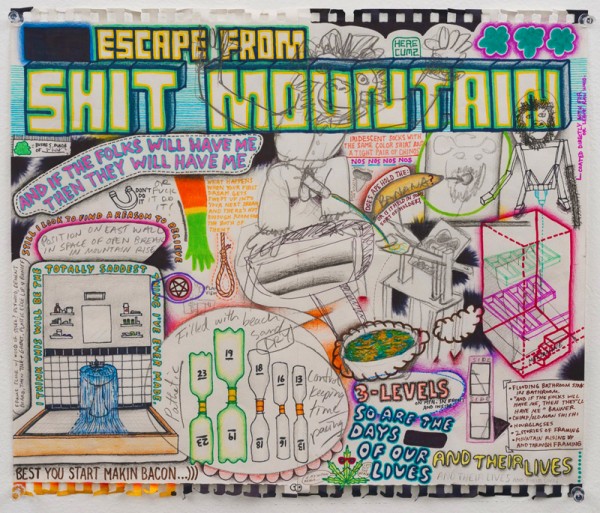

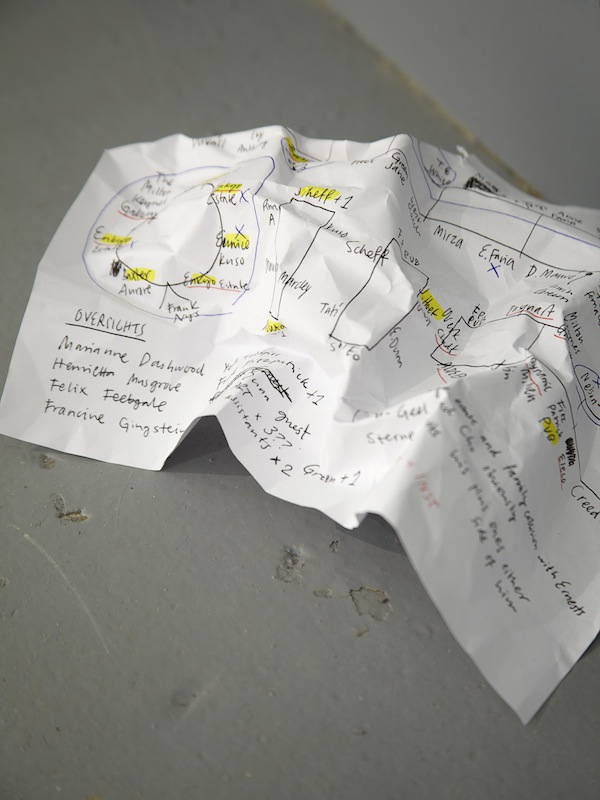

For the moment, the beating heart of Los Angeles’s Pacific Standard Time is Betye Saar’s installation Red Time, 2011, at Roberts and Tilton. Saar has transformed the middle room of the gallery into a shrine for past, present, and future, painting Roberts and Tilton’s interior room a bright red and allowing a variety of her customary assemblage works to act as friends and neighbors to each other, despite where they were collected from or when they were made. In fact, one of the most striking things about Red Time is the position it takes on memory and history. While Saar has divided Red Time into three separate sections–“In the Beginning,” “Migration and Transformation,” and “Beyond Memory”–she has also unified them through her use of a singular, strong background color and their enclosure in one small room.

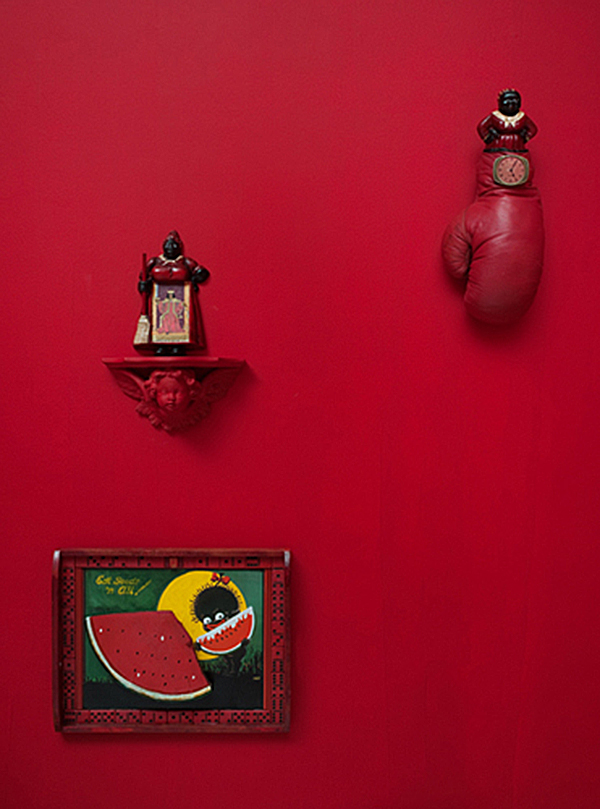

Betye Saar, "There Will Be Blood," 2011. Mixed media assemblage. 22.25 x 22.25 in (56.5 x 56.5 cm). Image courtesy of Roberts and Tilton Gallery.

Saar first rose to prominence in the 1960s as a Joseph Cornell-inspired assemblage artist who insistently tackled issues of race and history, and these issues remain central, both figuratively and literally. Many of the pieces that make up the “Migration and Transformation” section of Red Time, which occupies the wall opposite the room’s entrance, are radical détournements of Aunt Jemimah and Uncle Tom figures, a technique that Saar may have been the first to utilize and perfect. In fact, it is the juxtaposition of the pleasing formal rhythms, the coziness of the physical space, and the chilling historical narratives referenced by pieces such as There Will Be Blood, 2011, To the Manor Born, 2011, and Is Jim Crow Really Dead, 1972, that drives the work.

Betye Saar, "To the Manor Born," 2011. Mixed media assemblage. 11.5 x 20.5 x 2.25 in (29.2 x 52.1 x 5.7 cm). Image courtesy of Roberts and Tilton Gallery.

Among the works that Saar felt absolutely needed to be present in the installation is Red Ascension, 2011, a wooden ladder hung toward the top of the wall in “Beyond Memory.” Nestled amongst the rungs are wooden sculptures that tell a familiar story: an African mask, several wooden ships, chains, and a crescent moon and star. The ladder points viewers to the wall that is both the first and last in the exhibit, the wall to which their backs are turned for the majority of time they are in the room. It is the wall with the entry and exit door, on which a series of masks hang, looking back at the viewers with all manners of expression. Red Time is not solely a time of despair or anger. It is also a time of rebirth and open-ended questioning.