Iwan Effendi, The Crane Song, 2011, Acrylic on canvas, 100cm x 150cm. Image Courtesy of Yavuz Fine Art.

The joy and plight of many contemporary, Western-centric cultural practices today is the recognition that artistic shouldering of the collective burden of history does not necessarily attribute any value to the work. At worst, it is unfashionable and counter-productive to contemporary discourse; at best, it provides a vague notion of plurality and diversity that benefits a particular portion of the arts patronage. On the contrary, contemporary Asian art’s transformative power and value in the region, almost always lie in the recollection of the memories of post-war political independence, the marvel at socio-economic progress and sorrows of rapid industrialization.

In 1965, Indonesia found itself once again at a political crossroads after having endured an extended period of political instability since securing independence from Dutch colonial rule. In the twilight of President Sukarno’s rule in 1965 marked by bitter ideological conflict and political polarization, a coup at the end of September triggered a widespread wave of violence that brought General Suharto to office for over 3 decades. Generations removed from these events after 5 decades, the suppression of dissident artistic voices in the Suharto’s iron-fisted rule mean that contemporary Indonesian artists have only in recent years, begun their cathartic response to the trauma.

Eye of the Messenger by Iwan Effendi at the Yavuz Fine Art Gallery is such a response, interrogating the construction of Indonesian history in political upheaval of the 1960s and ultimately acknowledges that the socio-cultural and political discourses surrounding these years are cultivated, cultured and fabricated. As Walter Benjamin wrote, the craft of storytelling, does not aim to convey the pure essence of the thing, like information or a report, [but instead] sinks the thing into the life of the storyteller, in order to bring it out of him again. Similarly, a desire to contribute his own gesture of political resistance and social commentary underlies Effendi’s surrealistic images through a combination of word-and-image binary that is part-storytelling, part-myth and part-reality.

Iwan Effendi, Long Lost Memories, 2011, Acrylic on canvas, 70.5cm x 150cm. Image Courtesy of Yavuz Fine Art.

Iwan Effendi, The Bird Who Feeds The Fish, 2011, Acrylic on canvas, 70.5cm x 150cm. Image Courtesy of Yavuz Fine Art.

“Here I tell you, my friends,” Effendi writes in his catalogue, “a story where history was buried.” A large green tree with all-seeing eyes dominates Treasure Hunt (2011); The Crane Song (2011) is a diptych of opposing colours of blue and orange tones composed of a man who wears eyes as his cloak; Long Lost Memories (2011) is a piece of bulbous objects, bird eggs and birds that peer disconcertingly into nothingness. “But thank god, our eyes can’t lie,” Effendi further remarks. Ocularity and perception feature prominently in his canvases; the physical eye, and by extension, the visual experience, is used as a cautionary metaphor because of its ability to fall prey to yet simultaneously, resist manipulations.

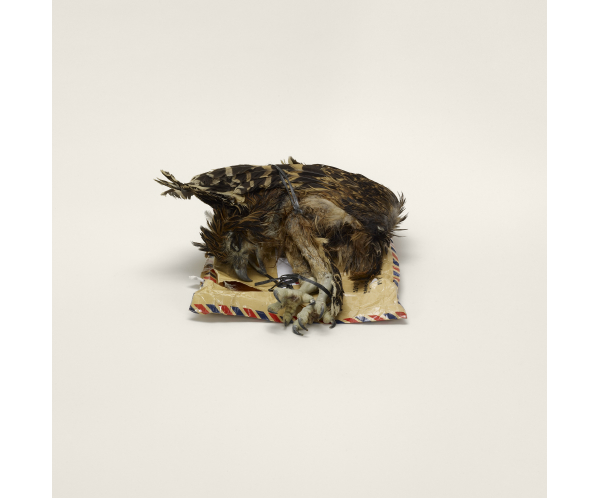

Iwan Effendi, Eye of the Messenger 2011, Installation View. Image Courtesy of Yavuz Fine Art.

The works in Eye of the Messenger are ironic and multi-layered: dismembered, colourful body parts float in the dimensional space of the canvasses and are tacked onto each other. They can’t be contained by the boundaries of canvas, spilling out of the seams and onto the surrounding white walls. Unlike the luminous simplicity and crack-quality of flat-faced satiric drawings that invite ridicule and laughter, Effendi’s cartoonish works cry out like multiple voices in a Greek tragedy clamouring to claim their own truth. In this context of use, reception and exchange, Effendi’s works accrue a varied interpretive history of – and perhaps even grant absolution to –those who have found finally regained their silenced voices.

***

Eye of the Messenger is on show at the Yavuz Fine Art Gallery until 13 November 2011.