David Shrigley, How are you feeling today? (2012), billboard, 25 x 75 feet, courtesy of Anton Kern Gallery

Running alongside Tenth Avenue for approximately twenty blocks in Chelsea, The High Line has become a household term amongst Manhattanites since 2009 when it first became accessible as a public park. Since then – and especially within the last year – The High Line has ignited widespread murmur relating to its breathtaking architecture, imaginative urban integration and more recently its emergence as the local gallery district’s – if not New York’s – most imaginative sites for exhibiting contemporary art. Opening April 19th was The High Line’s first ever group exhibition entitled Lilliput which included the works of Oliver Laric, Alessandro Pessoli, Tomoaki Suzuki, Francis Upritchard, Erika Verzutti and Allyson Vieira. Alongside this exhibition, Uri Aran’s sound installation opened on the same day only then to be followed by Alison Knowles’ public performance Make a Salad on the 22nd. David Shrigley’s How are you feeling? (2012), presented as a giant billboard over West 18th Street, and Sturtevant’s Warhol Empire State (2012), a video projection that starts at dusk of Andy Warhol’s Empire (1964) video, debuted earlier in the month to launch the Friends of the High Line’s 2012 Spring Art Program and High Line Commissions program for public art. The openings this month, surpassing the previous years in numbers of art pieces alone, has proven that this year’s arts program is making a vigorous effort to present art to the public with a bang.

Sturtevant, Warhol Empire State (2012), video projection, image courtesy of the artist

The High Line as we know it today exists upon the skeleton of a freight line that once was the manifestation of a public-private project called the West Side Improvement during the 1930s. However, that was the date that the freight lines were lofted 30 feet above street level after having existed as street-level railroad tracks some odd eighty years prior. During this time, The City and State of New York agreed to take on this massive industrial project due to the fact that Tenth Avenue became known as Death Avenue, a nickname indicative of the innumerable deaths caused between street traffic and the railroad. This was no small project, not least of all financially as it was quoted to be a $150 million dollar expenditure then, and that’s more than $2 billion dollars today.

Building the high line, November 20th 1932. Image courtesy of www.thehighline.org

Trains of food freight and both manufactured and raw goods ran until 1980 at which point the ensuing minimization of the railroad became obsolete due to redundancy and the upsurge of trucking transport. In the face of threatening demolition, Friends of the High Line was established in 1999 as a non-profit by Joshua David and Robert Hammond to preserve the historical lineage and neighborhood aura that the High Line had solidified. An all-star architectural and landscape design team made up of James Corner Field Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro (along with a large selection of horticulturists, gardeners, etc) was chosen in 2004 and by June 9th 2009 the first section (Gansevoort Street to West 20th Street) of The High Line as a public park opens, with the second section (West 20th Street to West 30th Street) to follow in 2011.

Allyson Vieira, Construction (Rampart) (2010), Bronze, 14 x 14 x 18.5 inches, courtesy of Laurel Gitlen Gallery, New York

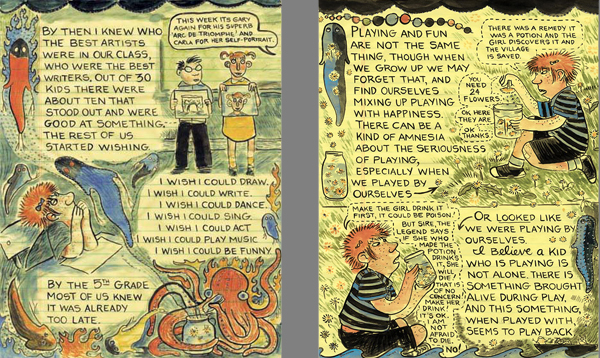

Since 2009, The High Line has become known as a trendy jaunt-spot in Chelsea where the ultimate people-watching activities and pleasure strolling can be had. This year the public will see the launch of a program called High Line Commissions with the opening of the first ever group exhibition Lilliput to be held on The High Line. This exhibition will present the works of six artists working internationally with, as the title would suggest, small sculptures placed along The High Line’s pathway. This title is taken from Jonathan Swift’s novel Gulliver’s Travels in which the imaginary country of Lilliput is home to gnome-sized people no bigger than six inches. The various diminutive sculptures are set within the various niches of landscape along the park walk and offer a sort of Easter-egg hunt of sorts, inviting the public to uncover the various works of art.

Pieces such as Allyson Vieira’s Construction (Rampart) (2012) respond to the local vegetation and ecology of the area with her pyramid of bronze cast paper cups that fill with rain or fallen leaves from the garden bed above. Other works such as The Seduction (2012) by Francis Upritchard are less so adapted for the localized flora but speak to the Lilliputian theme of fairyland idols with two miniature-sized apes frozen in an explorative embrace. Also apart of this spring’s High Line Commissions is Uri Aran’s sound installation Untitled (Good & Bad) (2012) provides a spoken list of arbitrarily categorized animals into “good” or “bad” that billows from gardens below. Coming in May, a much anticipated installation of Thomas Houseago’s sculpture Lying Figure will be on view under The Standard.

Francis Upritchard, The Seduction (2012), Bronze, 18 x 9 x 8 inches, Courtesy of Kate MacGarry, London

Friends of the High Line have initiated other programs such as the High Line Performances, High Line Billboard and High Line Channel that serve as varying avenues whereby art mediums can be exhibited. Opening on April 5th, David Shrigley’s 25-by-75 foot billboard How are you feeling? presents a short dialogue in black and white speech bubbles, hovering over a parking lot at West 18th Street. Shrigley’s dry and melancholy humor severs the socially fabricated fluff in monotonous conversation and pinpoints exactly what we all may be feeling but are too nervous to say: “I’m feeling very unstable and insecure […] I am in a bit of a rut creatively as well”.

This year’s itinerary for the High Line Performances will include performances by three female artists (Alison Knowles, Channa Horwitz and Simone Forti) on and around the High Line, the first of which was preformed last Sunday April 22nd by Alison Knowles’ Fluxus score Make a Salad. Originally performed in Baltimore, Maryland in 1962 has been performed several times around the world and includes the preparation of a salad for a large group of people. Launching the High Line Performances program, Knowles’ piece included the preparation of locally sourced salad ingredients tossed from the upper level to the lower level of the walkway and then served to the public. Though it was a rather cold and rainy day, otherwise unpleasant to be frolicking out of doors to eat a salad, the performance was lively and ignited a grouping of people of all ages in an appropriately themed Earth Day get-together.

Alison Knowles, Make a Salad (1962–present), Image: Tate Modern, London (2008)

I have to applaud the work and organizational efforts of the Friends of the High Line for their inception of the public art programs, and not to mention their unmentioned but as equally remarkable endeavors in the realms of music and food. The High Line as a public park has provided the support for not only a exceptional pleasure destination, but also a cutting-edge platform for contemporary art. I am always fascinated with the seemingly pervasive dialogue relating to the inaccessibility of contemporary art and thus I have always been an advocate for the commissioning of public art. Public art, as inconspicuous or ostentatious it may be, has the power to engage a public (a cross section in a vast demographic) who may not otherwise seek out an interactive relationship with art. Pieces such as the ones mentioned above all own that quality of engagement: the characteristic of calling forth a questioning, a reflection or even a happenstance double take, and sometimes that’s all an art piece needs to fulfill its role in the social sphere.

Please visit www.thehighline.org/art for a schedule of past, current and upcoming exhibitions and performances on The High Line and additional information on artists. Please visit the site for further information regarding The High Line’s events, public programs, memberships and history.