Elsewhere

dOCUMENTA (13): A Bit of Recovery

Song Dong, "Doing Nothing Garden"

Working in the press office of the dOCUMENTA (13) in Kassel, Germany, I have been confronted with media representatives from all over the world in all matter of sorts. Their attitudes have varied from excited enthusiasm during the preview days to defeated exhaustion after hours and miles of contemporary art navigation. It must be said, these nearly 3,000 journalists are troopers. They often come misdirected with maps and muddy shoes having traversed the city in attempts to see the of art dOCUMENTA (13) in a short amount of time. They often come asking for tips. I am asked what to see when one only has two days or two hours, how best to route one’s way through the exhibitions, or most interestingly common, has been the question of where to go to ascertain a good mood.

Director Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev gave the dOCUMENTA (13) the theme of “Collapse and Recovery,” and the truth is, it’s an exhausting one to take in. While many of the exhibits are inspiring in their existential explorations, let’s face it: contemporary art can be depressing. When facing topics of mankind’s disconnectedness, ego and destruction, war and terror, human suffering and loss, we can find ourselves feeling defeated. Along with recommendations for gelato and bratwurst, I have been suggesting a walk through Karlsaue Park.

Christian Phillip Müller, “Swiss Chard Ferry (The Russians aren’t going to make it across the Fulda anymore)"

A sprawling expanse of lush green parted by still canals and tranquil streams, ornamented with classical temples and picturesque bridges, the Karlsaue was originally intended as a pleasure garden. The 16th century park extends for 17 miles and for the 100 days of dOCUMENTA (13), it is a main venue for the exhibitions. Artists have created public sculptures, gardens, sound installations, and interactive mixed media works. As it is described in the guidebook, the park is home to: “a number of detached small houses containing artistic projects, the Grimm brothers’ tales, aesthetics, and politics, and how to be together separately.” While the subject matter addressed in the works of Karlsaue is not always breezy, it focuses perhaps on the “Recovery” aspect of Christov Bakargiev’s theme, and the environment is breathtaking.

Massimo Bartolini, "Untitled (Wave)"

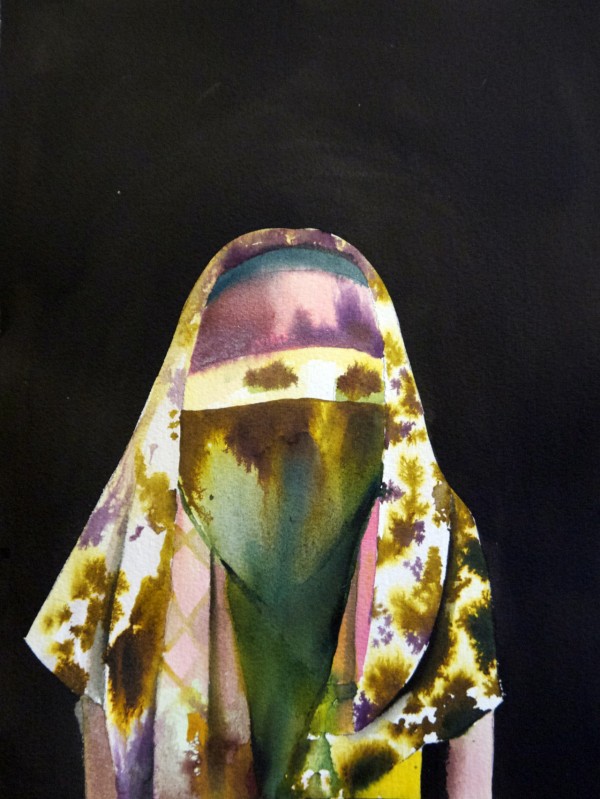

One might begin a Karlsaue tour at the baroque Orangerie, to view the work of Jeronimo Voss, Eternity through the Stars. Voss’ installation is composed of two parts, one at the planetarium and one in the Cabinet of Astronomy and Physics of the Orangerie. The artist works with light, projection, image, and text in dealing with astronomical processes to document history. From the steps of the Orangerie, one looks onto a green expanse of park and is confronted with the work of Italian artist Massimo Bartolini as well Chinese artist Song Dong’s hard-to-miss creation. Bartolini’s Untitled (Wave), is a minimalist construction of stainless steel, engine, water, and barley: a rectangular pond of water in constant wave-like motion. Bartolini is known for his interest in combining organic with man-made materials, bringing the viewer to observe mechanical constructions in natural environments. Song Dong has also added to the visual landscape of the park with his Doing Nothing Garden, which essentially is an accumulation of organic material and rubble: waste. Aside from being a 20 feet tall mound surrounded by red tubing and dotted by neon Chinese characters that read, “Doing” and “Nothing,” the project fits in with the natural environment. Growing native grasses and flowers, the garden is integrated; it is a thriving organism and it is an artificial landscape, beckoning the question- can doing nothing lead to creating something?