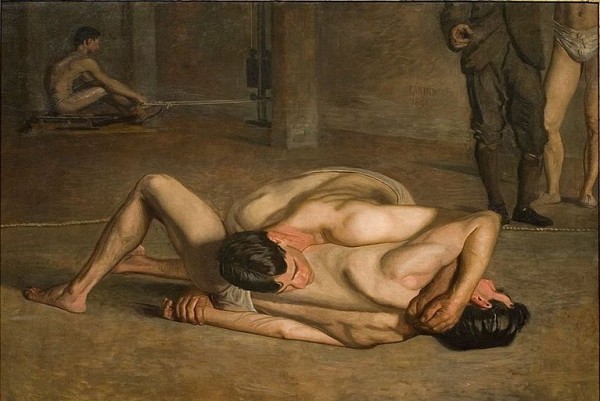

Lori "Lolo" Jones, HBO’s "Real Sports" in 2012, discussing her status as a virgin.

I am consumed by the Olympics. I’ve been counting down the seasons until the summer of 2012 and the days until July 29th. When the Olympic Games are being televised, I schedule my work and social life around watching my chosen events (gymnastics, swimming, and above all, track and field). This is a good moment to include the information that I was competitive runner, starting to train seriously even before the onset of puberty. Though I no longer participate in the sport and haven’t since I finished college, I revel in the one time, every four years, that it is performed internationally at its highest levels, and that other people care about it enough to watch it unfold in their living rooms.

One of America’s great hopes in track and field this summer in London is a hurdler by the name of Lori “Lolo” Jones. Though she is a few years older than I, we overlapped during our time in college; I was competing for UCLA when Jones was attending Louisiana State University (a longtime sprinting powerhouse). I never met Jones, but she once tried to steal my friend’s football-playing boyfriend, so I never thought that highly of her character. Athletically, however, she is an animal. While at LSU, Jones was a three-time national champion and eleven-time All-American in the 60- and 100-meter hurdle events. Once out of college and a pro athlete, Jones was the first woman ever to claim back-to-back World Indoor titles in the 60 meter hurdles while setting an American record in the process. How to describe these feats? Imagine being born with the right physiology, sense of purpose, and ability to absorb and withstand pain. Imagine being better at something than thousands of people who are really good at that same thing. Imagine being a woman, who, in front of the whole world, is unafraid of winning.

Lolo Jones, I must add, is quite beautiful. She is of French, African-American, Native-American, and Norwegian descent. She has wide cheekbones, green eyes, and a warm, easy smile. Her body is incredibly toned and muscular, but doesn’t tread into androgyny, as is the case with many Olympic-grade female sprinters. Being wildly attractive doesn’t hurt in winning her commercial endorsements — such as one from the oil company BP — magazine pictorials, and general mass appeal. But given her winning record, I can confidently say she would have accrued this attention anyway. Jones is an unmistakable champion. And, as the world learned a few months ago, she is a twenty-nine year old virgin.

Jones in a promotional photograph for Red Bull, one of her sponsors, 2012.

Much has been made of Jones’ May 22 proclamation of virginity, announced of all places on HBO’s Real Sports with Bryan Gumbel during a segment called “Olympic Sacrifices.” “It’s something, a gift I want to give my husband,” Jones said, continuing: “This journey has been hard…It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life. Harder than training for the Olympics. Harder than graduating from college has been staying a virgin before marriage.” She was at once self-deprecating and awkward in her delivery, clumsily justifying her choice to “remain pure” as a response to the dissolution of her parents’ union (they broke up after being together for twenty years and never marrying). She ends the segment by saying, “I guess I want that Norman Rockwell picture.” Since the interview, her Twitter followers (Jones generally posts between two and five times a day) have risen 40 percent, and her story has been picked up by People magazine, the Los Angeles Times and the Washington Post, among many others. Donald Trump, who has 1,320,454 followers on Twitter at the moment, wrote: “Lolo Jones, our beautiful Olympic athlete, wants to remain a virgin until she gets married — she is great.” The first comment under the YouTube clip of the interview, which I urge you to watch, reads: “Finally somebody that does the right thing!!!!!!!!!”

In light of this (largely) positive response from the public, Jones’ dissenters are quick to bring up the fact that she has posed, scantily clad, for several magazines.[1] Most recently, she was photographed fully nude and in a coy pose for ESPN Magazine, which has anointed her the “sexiest female Olympian.” But this is a tired argument, isn’t it? I’m less interested in the fact that Jones promotes a highly sexualized image of her body despite claiming moral virtue; Britney Spears, Jessica Simpson, and a plethora of other teen pop-tarts drained anything interesting or unpredictable about this “look-but-don’t-touch” sexy schoolgirl subterfuge in the late 90s. There is something decidedly more complicated and problematic about Jones’s recent declaration, and that shifts the critical conversation. Jones is not a pop star — a person whose very career hinges on the strategic contradictions of their public image. Rather, she is something less packaged and more aspirational, yet still bound up in the world of the bodily performance: a championship athlete. And not only any athlete, Jones is our great hope, who, barring injury, will likely win several gold medals in a few weeks.

“A boxer is his body,” wrote Joyce Carol Oates in her seminal 1987 book On Boxing,[2] and the same could be said of any Olympic-caliber athlete — particularly those who compete independently of external equipment or an immediate team structure. Jones has trained six hours a day, six days a week, for the past twelve years. That is almost 25,000 cumulative hours. Can you imagine that reality? Jones is training as you read these words on your computer screen. She is wholly accustomed to a life of the body — life as body, Oates would argue — which is punishing, ecstatic, and that above all, taps a primal consciousness.[3] How then, in a profession dedicated to pushing the boundaries of physicalized performance, is one to consider the disavowal of sex and suppression of desire? I am not sure I have the answer to this, but it’s a question worth asking.[4]

Jones poses in the pages of ESPN Magazine.

I have to admit, it is difficult to set aside here my belief that celibacy until marriage is a patriarchal anachronism that entails withholding (primarily female) sexuality as a weird prize. I can’t possibly do better on this than Emily Shire of Slate magazine, who wrote, on May 31st: “It’s disheartening that [Jones’] choice to remain a virgin is not for her own sake, but someone else’s. If virginity is commodified into the “perfect gift,” it becomes about a woman pleasing a man rather than herself, and it is difficult to picture the determined and forceful Jones being that submissive in any other aspect of her life.” However, the concern of this essay — the entanglement of abstinence and the athletic body — is not political as much as it is cerebral. In her HBO interview, Jones stated that maintaining her virginity was “harder than training for the Olympics”, and it’s an interesting comparison.[5] Both activities demand discipline over bodily desire, though in different, if oppositional, forms; athletic discipline requires the willing application of self and body, while the discipline of celibacy requires its continued refusal. Jones’ sexual status is of course her choice, but needless to say, it appears to me as perfectly incongruous with the virtuous rapture and abandon of athletic life.

Some people believe that Jones is not in fact a virgin. But who cares? She has publicly stated that she is, and that is what matters. Of course, if she weren’t a woman, much less a beautiful woman, her sexual status would not command so much media attention, not be considered the ‘prize’ that it is. Ultimately, Jones should decide if she wants to win the trophy, or be one. It’s a consequential distinction of which she appears dangerously unaware.

——————

[1] On May 25th, Twitter-user Taylor Maddox wrote on Lolo’s wall: “Respect n appreciation 4 ur purity, but I can’t wrap my mind around the body pics. Seems incongruent to ur strength and Christ :/)”, to which Jones responded: “go to a museum & look at naked pictures/statues of ppl & its considered art but what I did is not? u see no parts exposed.” http://twitter.com/lolojones

[2] Oates, Joyce Carol. On Boxing. New York: Doubleday (1987): 72.

[3] In his 1994’s essay, “How Tracey Austin Broke My Heart,” David Foster Wallace wrote: “It is not an accident that great athletes are called “naturals,” because they can, in performance, be totally present: they can proceed on instinct and muscle memory and automatic will such that agent and action are one.” In: Foster Wallace, David. Consider the Lobster. New York: Little, Brown and Company (2005): 154.

[4] In thinking more about matters of sexual economy and ritual, I turn to Michel Foucault. I was amazed to realize that he in fact dissects the connection between athleticism and abstinence in some depth in The History of Sexuality: Volume 2, writing: “A moral victory which the athlete needed to win over himself if we wished to be capable and worthy of assuring his superiority over others; but also that of an economy necessary for his body in order to conserve strength, which the sexual act would waste on the outside.” It’s a bit limited for my own purposes, as Foucault refers only the restrictive habits of male athletes, e.g., a regimen of non-ejaculation pre-competition. Still: fascinating! In: Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Vol. 2: The Use of Pleasure. New York: Vintage Books (reprint 1990): 120.

[5] Interestingly, the use of the word “purity” in relation to Jones’s body stands in direct opposition to the recent, rampant steroid use in the sport, often referred to as “being dirty.”