Summer Reading

Summer Reading – Closed Circuits: A Look Back at LACMA’s First Art and Technology Initiative

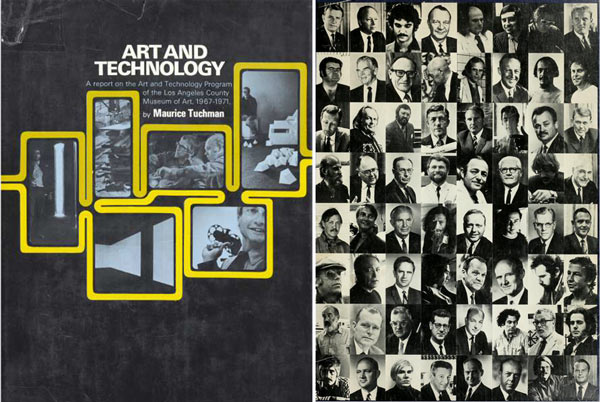

From our friends at East of Borneo, today we continue our Summer Reading series with an essay on LACMA’s Art and Technology initiative. Author Catherine Wagley notes: ’[…] the nostalgia for Art and Technology has much to do with the way the report suggests a moment when institutions were less careful about protecting their sponsors, when conflicts of interest could be openly discussed, and when a curator could publish pages and pages detailing how various collaborators did and did not get along.” This article was originally published on May 11, 2015.

“A Report on the Art and Technology Program of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1967-1971.”

It was 1969 when artist John Chamberlain decided to screen his film The Secret Life of Hernando Cortez in the RAND Corporation’s cafeteria. The artist, middle-aged and best known for the smashed-metal monuments he had been sculpting out of discarded car parts, was having a Warholian moment. He had even cast regulars of Andy Warhol’s Factory—scrawny, always smirking Taylor Mead and wispy Ultra Violet—as stars of The Secret Life, which he filmed in Mexico in 1968. Mead plays Mexican conqueror Hernando Cortez and cavorts, making treaties and wreaking havoc. Ultra Violet, taller than Mead and far more conventionally attractive, plays his mistress, urging him to privilege sex and vanity over duties such as fighting for his people’s freedom. At one point, a mountain lion eats an antelope onscreen.

The film ran once a day for three days. Then all screenings were canceled. “Word must have gotten to Washington, D.C., that RAND was showing dirty flicks on lunch hour,” Chamberlain wrote in a memo to curators at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, though it seems staff complaints, not politicians, were to blame.