Atlanta

Sprawl!: Drawing Outside the Lines at the High Museum of Art

Sprawl! Drawing Outside the Lines presents a compelling case for an expanded notion of drawing and draftsmanship in contemporary art. With over 100 drawings culled from artists and creative workers within the sprawling suburban metropolis of Atlanta, it’s a much-anticipated sequel to the 2013 exhibition Drawing Inside the Perimeter, which instigated the museum’s public commitment to acquiring and exhibiting the work of local artists. Sprawl! registers as a strong statement of institutional support and acknowledgement from the High Museum to the diversity of the artistic community working within and just outside the capital city.

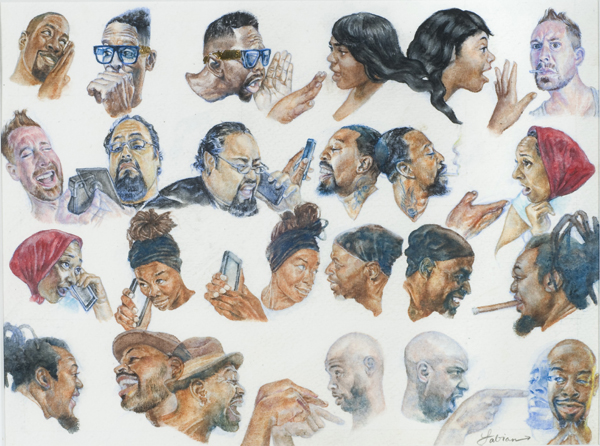

Fabian Williams. Gossip, 2014; watercolor on paper; 8 x 10 in. Courtesy of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta.

In regard to urban planning, sprawl—or the unregulated and uncontained expansion of bodies, buildings, industries, and urban traffic—is often used as a pejorative term. Like many cities, Atlanta struggles to form a stable identity in the aftermath of a series of gentrification booms (beginning in the late 1990s) that disturbed the historically dominant African American demographic with an influx of Hispanic, Asian, and white populations to the city. Paving the way for the demolition of public-housing projects and low-income initiatives that supported the residents of the inner city, Atlanta’s association with aggressive forms of urban growth finds a more utopian expression in this exhibition. Framed as a melting pot of ethnic and creative heterogeneity, Sprawl! equates the overwhelming influx of new inhabitants to the area with the sprawling, spreading, expansive processes of drawing itself.

This sense of connection and community is powerfully explored in Fabian Williams’ tenderly executed work Gossip, an appropriation of Normal Rockwell’s The Gossips (1948), both of which depict a taxonomy of social types or “characters” laughing, talking, and gesticulating. While the figures exude a sense of energy and liveliness that overwhelms the spaces of the other figures, the exaggerated expressions and movements rub uncomfortably against a form of a biting sarcasm that accompanies the history of pencil drawing and caricature. Reminiscent of the sketchbooks of the 18th-century British social satirist and artist William Hogarth, Williams’ work is as joyful as it is disturbing in its exploration of issues of social class, ethnicity, cultural stereotypes, mass technology, and 21st-century life in Atlanta.