Interviews

Interview with Johanna Hedva

Johanna Hedva is a Los Angeles-based artist and writer whose recent piece She Work was performed at d e e p s l e e e p, a private apartment in Los Angeles, from July 11–26, 2015. She Work is a queer adaptation of Euripides’ play Medea, in which Jason abandons Medea and their children, marrying a Greek princess to advance his political position. Medea decides to cause Jason the most amount of pain by killing his new wife and taking the lives of her own two children. Hedva’s retelling—littered with Tumblr memes, hashtags, and quotes from Girl, Interrupted—considers exile, courage, motherhood, and tragedy in the contemporary neoliberal landscape.

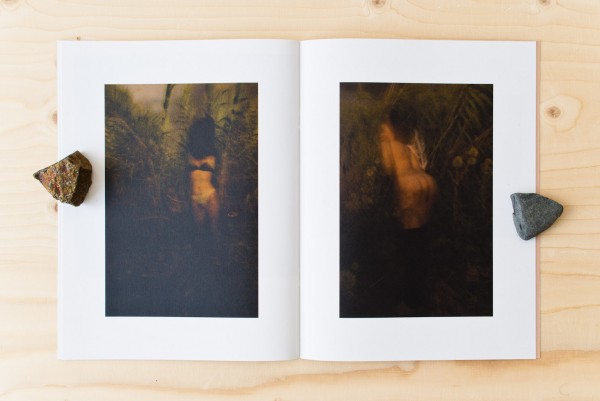

Johanna Hedva. She Work, 2015 (performance still of Nickels Sunshine); live performance; 1:5. Courtesy of the Artist. Photo: Emily Lacy.

Vivian Sming: Your latest performance is the fourth and final installment in The Greek Cycle series. Could you talk about the three other plays that led up to She Work? At what point did it become clear to you that Medea was to be the included as the final piece of the cycle?

Johanna Hedva: The Greek Cycle was born in 2011 in the wake of a miscarriage I had at age 27, which instigated an involuntary hospitalization, my first year of real madness, a divorce, and therefore Greek tragedies seemed the closest to home. Medea was the first play I wanted to do, to deal with all that shit, but I was so stunned, without power or comprehension of my situation, that I ended up doing Hecuba instead because I needed a bath of silence. Hecuba is the story of an old queen whose fifty children are all killed in the Trojan War. In Euripides’ play, she’s made inhuman by her grief, begging the men around her for an explanation or a little mercy, but nothing comes. At the end, a seer tells her she’ll end her life as a dog. I fully related to that, so I adapted the play into Motherload (2012), a 30-hour, five-day dream play that took place in the hallway of a school. It was somnambulistic, mostly silent, a bunch of sleepwalkers reciting lines from a script that was over 160 pages. Hecuba’s incomprehensible grief—so laboring but utterly non-redemptive—was a better fit at the time.