New Orleans

A Shared Space: KAWS, Karl Wirsum, and Tomoo Gokita at Newcomb Art Museum

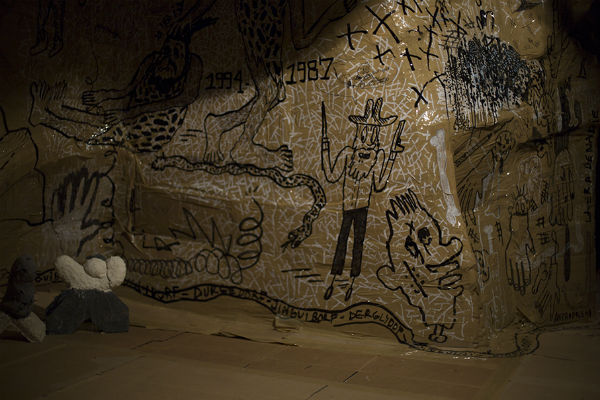

The history of the artist-as-collector is as long as the history of art itself. From Rembrandt to Damien Hirst, artists have amassed collections in order to satisfy a range of interests and obsessions. A Shared Space: KAWS, Karl Wirsum, and Tomoo Gokita, at Tulane University’s Newcomb Art Museum, consists of artworks culled from the Brooklyn-based artist, designer, animator, and commercial guru KAWS’s private collection, allowing the viewer a rare insight into the artist’s preferences as both a producer and consumer of works of art. Unlike more recent attempts to frame the personal collecting habits of an artist as a manic embodiment of commodity fetishism in the era of high capitalism, this exhibition asks viewers to reflect upon the correspondences between artist and acquisition and the complicated relationship that contemporary art exposes between taste, influence, and popular culture.

KAWS. Flight Time, 2015; acrylic on canvas; 84 x 72 in. Courtesy of the Artist and the Newcomb Art Museum.

Even across the diverse styles and interests of these three artists, linkages between content and craft are revealed. Weaving through the galleries, the succession of images feels like a series of slaps to the face as colors are taken to their saturation points and figures are monumentalized in scale and proportion. The dialogues composed by the careful placement of works provide the most powerful moments in the exhibition. KAWS’ deep black Michelin-like figure CHUM (2009) stands determinedly next to graphic paintings by Gokita, offering his protection to the naked and faceless vulnerables posed in the images, while ACCOMPLICE (2010)—a matte black toy bunny sculpture with large Xs covering his eyes—stands hunched in defeat across the room, out of sync with the bright canvases that surround him. Using the well-worn ethics of Pop Art to tease out the dark structures of commodity forms, KAWS’s sculptures allow these humorously irreverent figures to fester in their slick, expensive aura of pomposity and compelling iconicity.