Best of 2015

Best of 2015 – The Great Debate About Art at Upfor

DSAP director Patricia Maloney selected today’s installment for our Best of 2015 series: “Ashley Stull Meyers doesn’t shy away from calling out an exhibition with as grand a title as The Great Debate About Art for what it leaves unexamined. The effort to determine the limits or properties of what constitutes art is a quixotic task, and Meyers acknowledges the absurdity inherent in the premise right from the outset. Yet she doesn’t give the work itself short shrift, and it is her description of one in particular that keeps this review in mind at the end of the year. In unpacking Max Cleary’s To See You Again (2015) as ‘the exhibition’s most visceral attempt at affirming the trials and tribulations of makership,’ she encapsulates the challenge all artists and writers perpetually face: determining when a work becomes its ‘finished’ self.” This article was originally published on August 13, 2015.

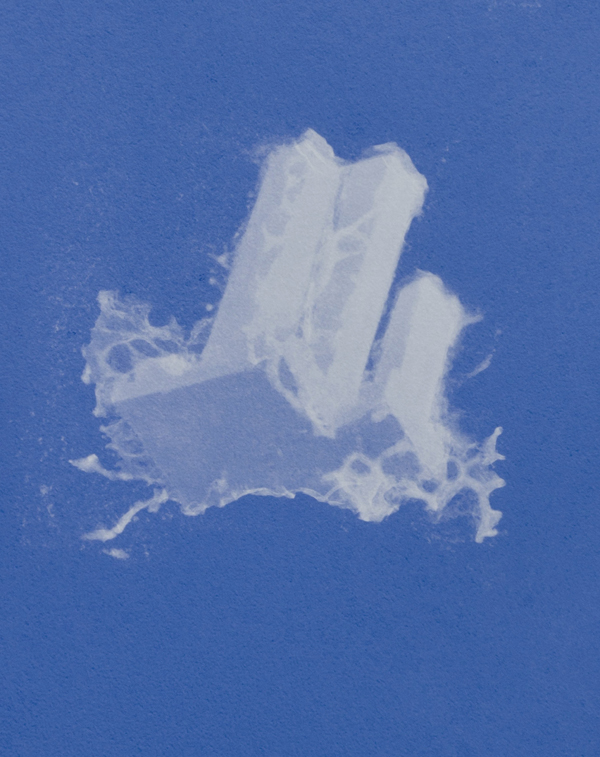

Ben Buswell. ABRACADABRA (Perish Like the Word), 2015; graphite and non-photo blue; 38 x 20 in. Courtesy of the Artist and Upfor. Photo: Mario Gallucci.

“Art” is a contentious word. Endless positing over any succinct, defining properties has spawned countless op-eds, theses, and textbooks. The topic is comparable to that of discussing religion in mixed company—differences of opinion have more than once drawn blood. The Great Debate About Art, currently on view at Upfor in Portland, Oregon, is a small group exhibition contextually centered on Roy Harris’ 2010 book of the same name. Co-curated by Upfor and Envoy Enterprises (NY), seven artists—Ben Buswell, Srijon Chowdhury, Max Cleary, Anne Doran, Zack Dougherty, Erika Keck, and Rodrigo Valenzuela—present ten works that (like Harris’ writing) philosophically wax and wane in their proposals.

Harris insists that the purpose of his research is not to further instigate a battle between mediums, schools. or –isms. Instead, his aims are epistemological. Is the trouble with the term “art” a linguistic issue? Should we suppose a standard of technical skill? Or is it content that wins the day? Who decides, and more importantly, what gives them the authority? Upfor and Envoy Enterprises optimistically postulate, “the artist.”

Ben Buswell’s Your Value Is My Law (2015) plays with notions of anti-art in its refusal to reveal an overt image. Beginning with a photograph of a purposefully unknown subject, Buswell alters the surface emulsion with a needle to create an arrestingly texturized white verso. The effect is historically reminiscent of Robert Rauschenberg’s Erased De Kooning Drawing. The photograph, framed backward, leaves only questions for the image that was. “Art,” for one thing, is about its ideas. Buswell embodies this presupposition not only in his layered choice of media, but also through the work’s title. The artist dually contributes ABRACADABRA (Perish Like a Word) (2015) to further consider “value.” Buswell acknowledges the nuances of technical dexterity and its effects on both the perception of skill and an artwork’s place in the commercial market. The drawing is composed of graphite and non-photo blue—a graphic-design material used to create marks visible to the eye, but not to the camera. In the presence of the original, each meticulously drawn striation is visible. The digitalized and printed counterpart, however, becomes something else entirely. It’s clean. It’s a cheat and thus holds considerably different value to a viewer with other (likely commercialized) aims.