Washington, D.C.

Robert Irwin: All the Rules Will Change at the Hirshhorn Museum

Robert Irwin has had a number of distinct careers as an artist, each with a distinct group of peers and beliefs. All the Rules Will Change presents the best known but least seen of these careers: the studio painter of the 1960s, who began the decade as a conventional Abstract Expressionist, and ended it by closing his studio and abandoning a practice of painting that had, he claimed, become too familiar.

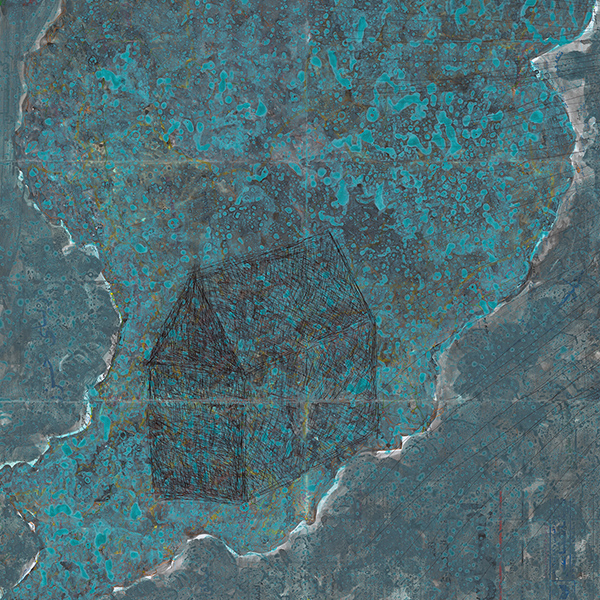

Robert Irwin. Untitled, 1959–60. © 2016 Robert Irwin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: © 2007 Philipp Scholz Rittermann.

Of this transformation, Irwin has said, “From about 1960 to 1970 [… ] I used my painting as a step-by-step process, each new series of works acting in direct response to those questions raised by the previous series. I first questioned the mark (the image) as meaning and then even as focus; I then questioned the frame as containment, the edge as the beginning and end of what I see. In this way I slowly dismantled the act of painting to consider the possibility that nothing ever really transcends its immediate environment.” [1]

Each step in the process yielded a new body of work, and the Hirshhorn presents these bodies in sequence. First, one encounters the Handhelds, austere miniature AbEx paintings set into heavy, crafted panels, each roughly the size of a laptop computer. Both their scale and name suggest a cargo-cult appropriation of digital tech, despite having been made at a time when computers were still room-sized and programmed with punch cards.