Summer Session

Summer Session: How We Read: Close, Hyper, Machine—Part 1

As part of our Back to School Summer Session we are exploring pedagogy and the state of learning in the arts. Today we bring you an article from our sister publication Art Practical by cultural scholar and author of How We Became Posthuman N. Katherine Hayles. Considering national studies observing a decline in general reading abilities across the United States, Hayles differentiates between key reading techniques employed by print versus digital texts. Her explication of these different patterns offers up new pedagogical strategies for reading that suggest that digital and print reading could inform one another rather than work in opposition. This article was excerpted with permission from the ADE Bulletin No. 150 (2010) and republished December 4, 2013.

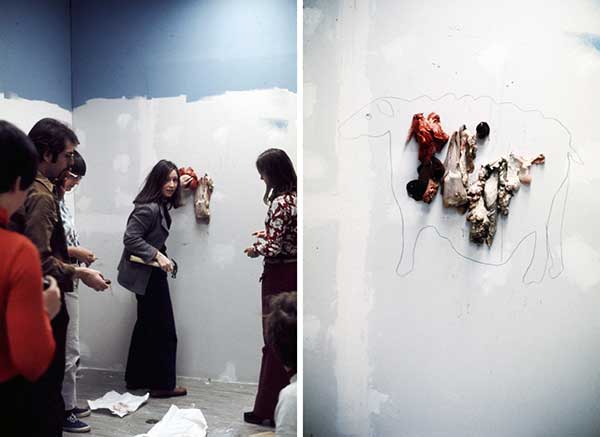

Catherine Wagner. Beloved, Toni Morrison from the series trans/literate, 2011; archival pigment print with braille; edition of five; 21.75 in. x 49.13 in. diptych. Courtesy of the Artist and Stephen Wirtz Gallery, San Francisco.

The evidence is mounting: people in general, and young people in particular, are doing more screen reading of digital materials than ever before. Meanwhile, the reading of print books and of literary genres (novels, plays, and poems) has been declining over the last twenty years. Worse, reading skills (as measured by the ability to identify themes, draw inferences, etc.) have been declining in junior high, high school, college, and even graduate schools for the same period. Two flagship reports from the National Endowment for the Arts, Reading at Risk, reporting the results of their own surveys, and To Read or Not to Read, drawing together other large-scale surveys, show that over a wide range of data-gathering instruments the results are consistent: people read less print, and they read print less well. This leads the NEA chairman, Dana Gioia, to suggest that the correlation between decreased literary reading and poorer reading ability is indeed a causal connection. The NEA argues (and I of course agree) that literary reading is a good in itself, insofar as it opens the portals of a rich literary heritage (see Griswold, McDonnell, and Wright for the continued high cultural value placed on reading). When decreased print reading, already a cultural concern, is linked with reading problems, it carries a double whammy.

Fortunately, the news is not all bad. A newer NEA report, Reading on the Rise, shows for the first time in more than two decades an uptick in novel reading (but not plays or poems), including among the digitally native young adult cohort (ages 18–24). The uptick may be a result of the Big Read initiative by the NEA and similar programs by other organizations; whatever the reason, it shows that print can still be an alluring medium. At the same time, reading scores among fourth and eighth graders remain flat, despite the No Child Left Behind initiative. Notwithstanding the complexities of the national picture, it seems clear that a critical nexus occurs in the juncture of digital reading (exponentially increasing among all but the oldest cohort) and print reading (downward trending with a slight uptick recently). The crucial questions are these: how to convert the increased digital reading into increased reading ability and how to make effective bridges between digital reading and the literacy traditionally associated with print.