Play With Your Own Marbles

|

| Karl Haendel |

Play With Your Own Marbles is the title of a new exhibition currently on view at San Francisco’s NOMA Gallery. The exhibition, which is curated by Betty Nguyen, Creative Director of First Person Magazine, brings together three Los Angeles-based artists in an examination of artistic process and its relation to utility, both in object and image. The exhibition highlights the objects and cyanotypes of Walead Beshty, the meticulously rendered photorealist drawings of Karl Haendel, and the formal concrete “paintings” of Patrick Hill.

Play With Your Own Marbles is not only linked through the evident formal and aesthetic concerns of each artist, as the show is remarkably connected through its homogenized temperament, graphically monochromatic palette, and overall deconstructionist sensibility, but each artist also plays with a strong sense of irony through material, form and method of display.

|

| Patrick Hill |

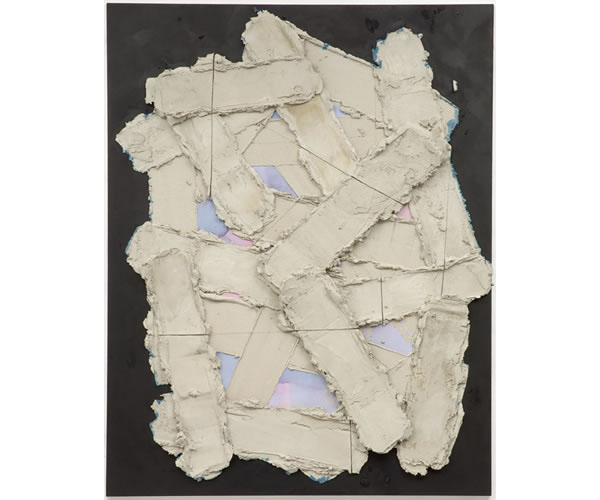

Patrick Hill has applied thick bands of concrete, absorbed and stained into a black velvety surface revealing small crevices of color, opening a dialogue between a strictly modernist approach to painting and the everyday utilitarian material of concrete.

Walead Beshty’s FedEx Kraft Box………… sculpture, which contains custom shatter proof glass cubes placed inside standard Fed-ex boxes, displays the evidence of wear as an object travels from one location to another. These ready made materials are further “improved” by the imposing alteration of travel. In addition to the sculpture, Beshty also presents several photographic images of isolated objects produced by placing the otherwise utilitarian forms on photosensitive paper, rendering them useless of their original function. Images of crumpled paper and eyedroppers begin to resemble abstracted paintings, drawings and monoprints further removing the viewer from the object’s original state and placing it more in the realm of the artifact.

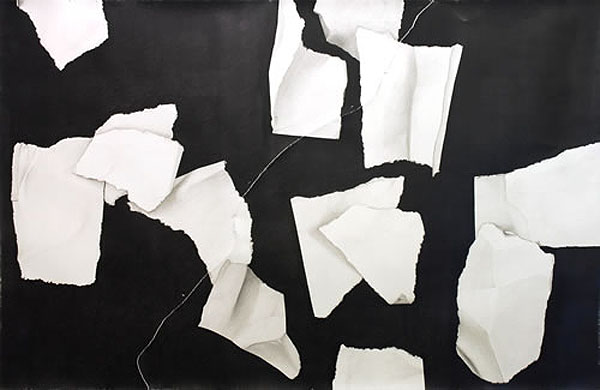

Karl Haendel’s photorealist graphite drawings subvert functional objects by manipulating scale, content and source imagery. Haendel’s imagery and method of presentation is generous in it ability to be easily recognized though careful rendering and specific depiction of everyday materials such as paper, razor blades, nails and paper clips. However, the work subtly unfolds and challenges the viewer through its coded symbols and methods of display. Haendel presents a delicately drawn image of ripped paper on a plywood platform supported by stacks of art magazines, which plays with the viewer’s physical perspective to drawing and the repetition of material (paper) through multiple forms. This work is presented along side images of blades mounted to wood gently resting against a wall and large scrolls of paper containing references of would be titles for the exhibition, all of which playfully discuss the relationship between concept and material.

The collections of work in Play With Your Own Marbles are subtly seductive, engaging the viewer first through a whisper and later through a tug of the ear. Each work takes the utilitarian object and subverts it to reveal new potentials that have the ability to exist on a sliding scale of completion, remaining in a state of flux both formally and conceptually.

Play With Your Own Marbles will be on view in San Francisco through October 3rd.