Drew Heitzler rephrases history in ways that seem both furtive and strangely revealing. In his most recent work, he culls characters, settings, and plots from the visual history of the still-young Los Angeles. Rearranging and re-imagining three films from the early 1960s, all of them productions in which the rebel spirit of Easy Rider seems to be slowly eating into the stylized melodrama of noir, and also gathering an expansive archive of still images from Hollywood of yesteryear, he’s created a narrative that confuses the past in order, paradoxically, to clarify the hidden truths about desire and culture that lurk beneath it.

Heitzler, who participated in the 2008 Whitney Biennial, recently exhibited at LAX Art and Angstrom Gallery among, other venues. for Sailors, Mermaids, Mystics. for Kustomizers, Grinders, Fender-men. for Fools, Addicts, Woodworkers and Hustlers, his current exhibition at Blum & Poe Gallery, closes January 30th.

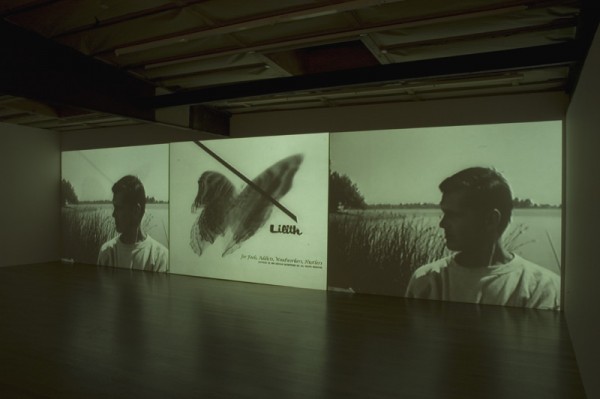

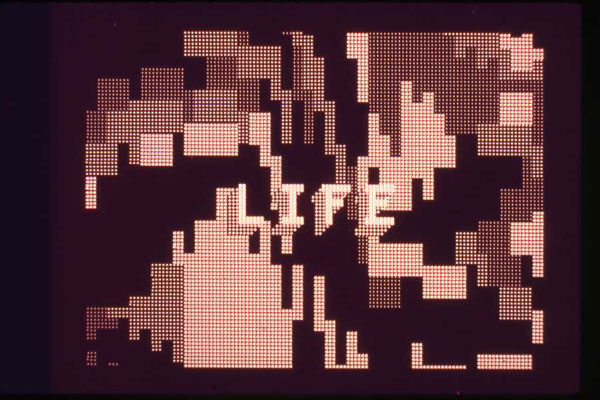

Drew Heiztler, "for Sailors, Mermaids, Mystics. for Kustomizers, Grinders, Fender-men. for Fools, Addicts, Woodworkers and Hustlers." Installation View. Courtesy Blum & Poe.

CW: Your current exhibition makes me think of remixes and mash-ups—art forms that are about rearranging someone else’s cultural product and telling a different story. What prompted you to re-edit historical film and images?

DH: Subway Sessions and TSOYW are two previous films I made and actually shot. The first on super-8, the second on 16mm (TSOYW was a collaboration with Amy Granat and was included in the 2008 Whitney Biennial). In both cases I relied heavily on the tropes of specific film genres. Subway Sessions used the aesthetics of 70’s surf films to tell the story of a certain time and place, specifically, Rockaway Beach New York just prior to September 11, 2001. TSOYW looked like a 70’s biker film and relied heavily on the tropes of that genre. So it wasn’t a big step to go from using the look of earlier film genres to actually using earlier films themselves. Also, I had read a book on documentary film making by Erik Barnouw that my wife Flora found for me in a thrift store. In the book, the Soviet cine-clubs were discussed. It seems that after the revolution it was impossible for Russian film makers to get film stock due to western boycotts. What they had in abundance were western news reel and even films that were being smuggled into Russia in effort to undermine the Revolution. The cine-clubs would re-edit these films and news reels in order to create new narratives that supported their cause. I liked this idea of re-ordering an existing cultural image to better fit your own perception of the world. It’s collage.

CW: How important is story-telling to you?

DH: Story telling is what I am interested in. I love those French paintings like The Oath of the Horatii or The Raft of the Medusa. They operate like movies. They tell stories which can exist at different allegorical levels.

CW: Each of the three films that make up for Sailors, Mermaids, Mystics. for Kustomizers, Grinders, Fender-men. for Fools, Addicts, Woodworkers and Hustlers. (Doubled ) were originally presented on their own, right? Why combine them?

DH: The combining of the films came out of a problem of exhibition. This show was originally scheduled to open at MOCA in May, 2009. Then it was postponed to September of that year and then postponed again to January of 2010 before it was eventually canceled all together. The result was that I had a long time to think about how these three films would be presented. I had always intended for them to come together as a trilogy, but as I kept messing around with ideas of how they would actually be presented in the gallery, they morphed into a triptych, becoming a whole new piece. What I discovered and enjoyed was that once the three individual narratives were doubled and superimposed over one another, they operated in a much more complex way. The individual narratives were still visible, but complicated by their interaction with one another. In other words, the lines of thought were confused, which seems to me much closer to the way we go through life. At least that seems to hold for me.

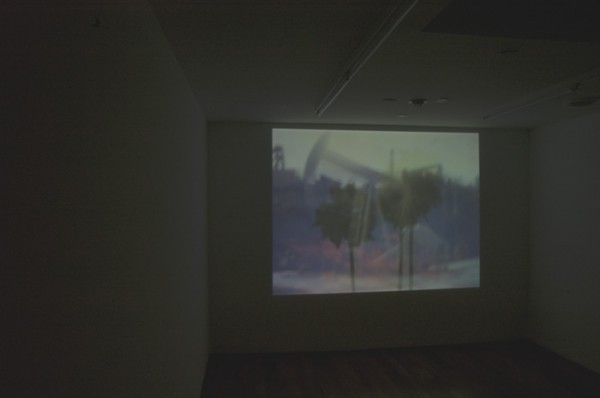

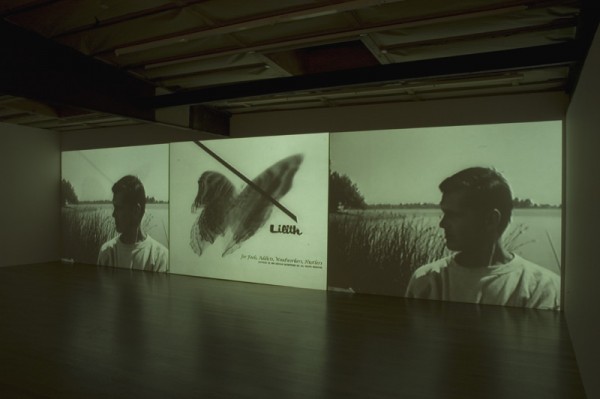

Drew Heitzler. Installation View. Courtesy Blum & Poe.

CW: The other day, you used the words “sticky stuff,” referring to the way the oil industry lurks underneath L.A. culture. I love those words and they’re definitely relevant to your work. How do you relate the historical, anthropological side of your project to its sticky, psychological underbelly?

DH: I think it has something to do with the problem of truth, or more accurately its impossibility. I came to Los Angeles with an idea of what I would find when I got here. It was the idea that had been presented to me, sold to me in a way. What I found was something completely different. History and anthropology work the same way. They present themselves as framing a truth while they are only presenting a perception (I was assistant to Fred Wilson for several years and I learned from him how important this idea is). However, the idea of truth is absolutely vital to our ability to exist as a society, this is common sense. Likewise, sublimation is absolutely necessary for the ego to exist within a society. There are rules to follow. Once again, the only way this sublimation works is to accept certain ideas, certain perceptions as true. But just like the oil that bubbles up into the sunny Los Angeles landscape, the sticky stuff that we sublimate, keep subterranean, or relegate to the subconscious can’t be kept at bay. It always bubbles up.

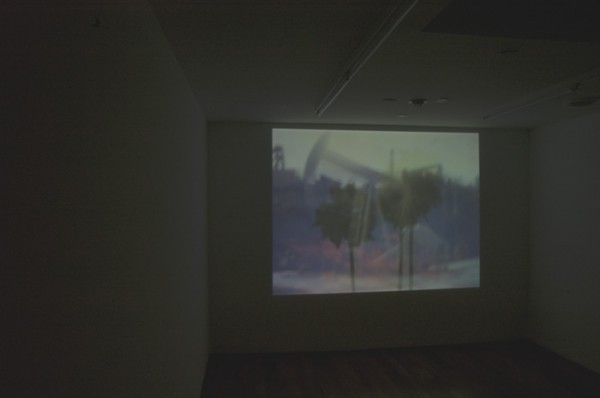

Drew Heitzler, "Untitled (Ladera Heights)," 2007. Installation View. Courtesy Blum & Poe.

CW: While the story you’re telling is ostensibly about the past, it seems really timely. As you developed this work, were you thinking of anything happening on today’s cultural landscape?

DH: Once again, I’m going to bring up The Oath of the Horatii (god, I love that painting). The painting is a depiction of a moment of Roman lore but this is not what the painting is about. It is a call to arms for a new Republic in France. This is the subtext. So while the historical anthropology that I am engaged in is ostensibly about historical power structures in Los Angeles, I believe that when the work is looked at closely, the relationships to our current cultural moment are clear.

CW: On a related note, I was reading Camille De Toledo’s Coming of Age at the End of History the other day. This passage, about a new breed of romanticism, reminded me of you: “We kept alive the idea that man was capable of acting upon History, but we abandoned the . . . heroism of the avante-gardes that imagined they could overturn it.” Thoughts?

DH: This goes back to the idea of truth that I addressed in a previous question. I feel that as we have observed how the successive avant-gardes were absorbed into the monolith of capital it became more difficult to take the idea of revolution seriously. One truth gets replaced by another truth to then be absorbed by the previous truth and none of them are true anyway. I am quite certain that it is useless to try and overturn the dominant discourse as the result is merely a different dominant discourse. But what remains is agency. I feel that it is important as an artist to act upon the dominant discourse not with the intent of overturning it, but with the intent of revealing its contradictions; confusing it and so bringing it closer to a universal idea, which is as close to an idea of truth that I am willing to entertain.

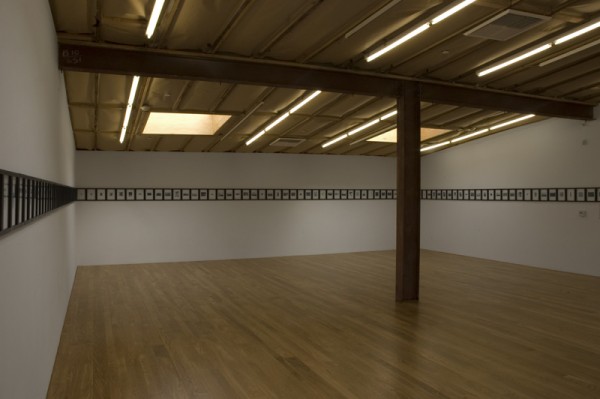

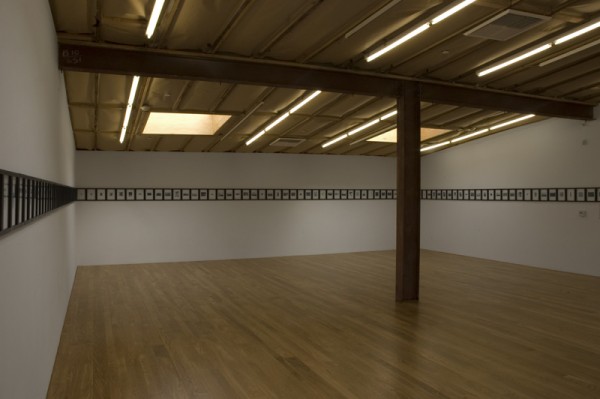

Drew Heitzler. Installation View. Blum & Poe.