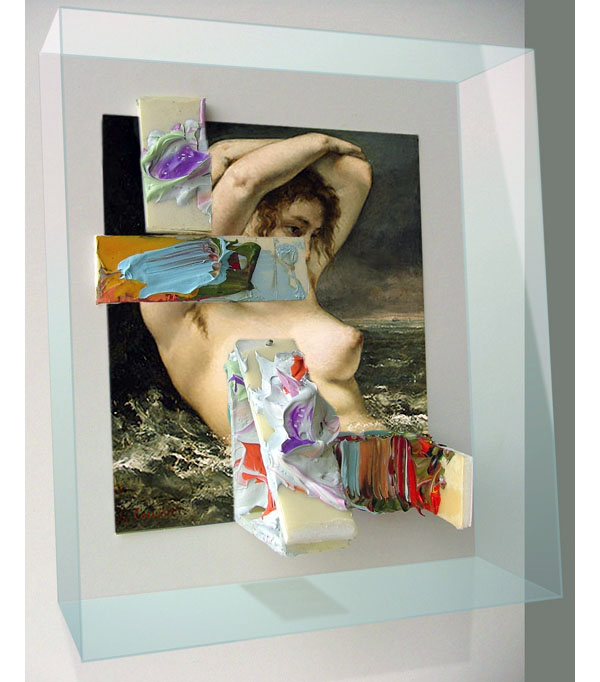

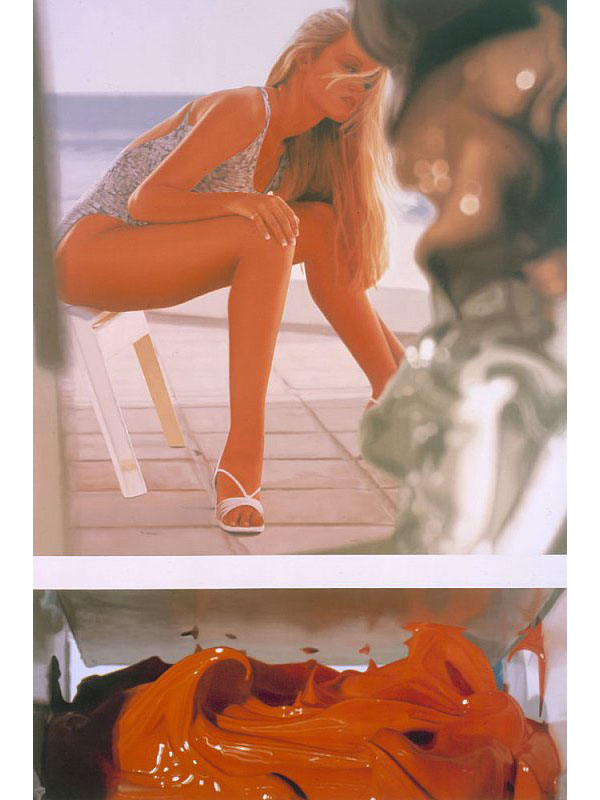

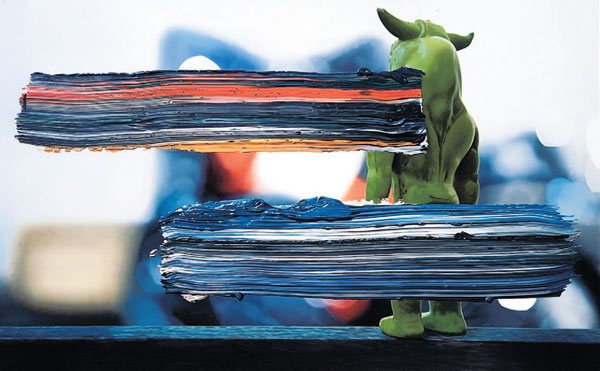

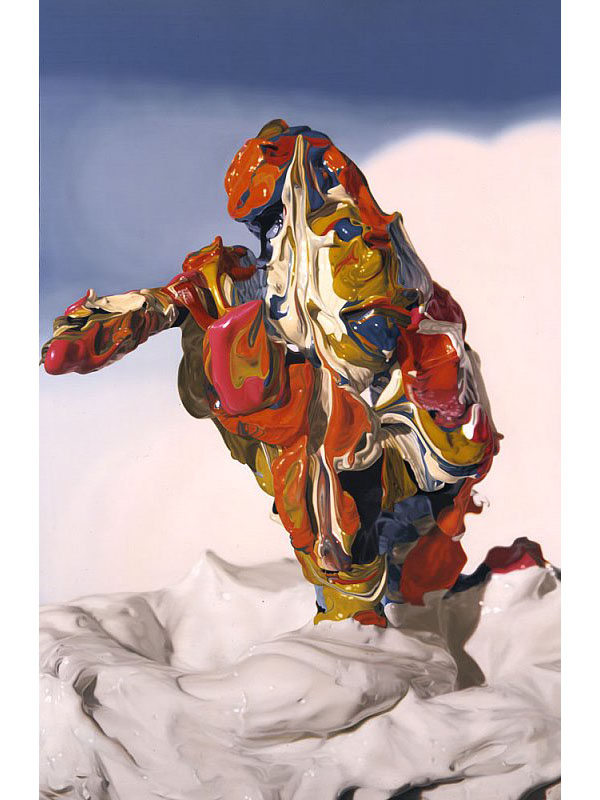

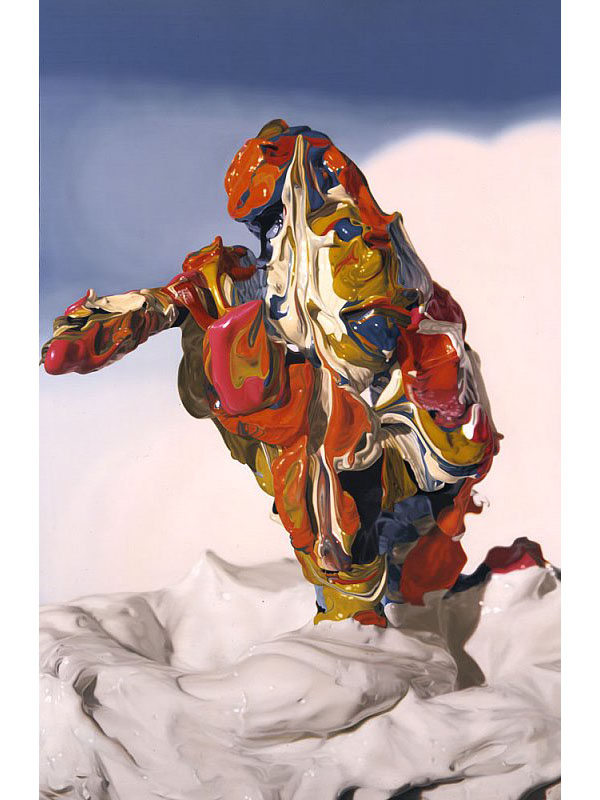

Richard Patterson emerged in London at Damien Hirst’s Freeze exhibition in 1988 as one of the YBA group. After moving to New York he eventually settled in Dallas. He is represented by Timothy Taylor Gallery in London and James Cohan Gallery in New York. He is known for paintings that combine imagery culled from popular culture and art history with painstaking detail. Combining car culture, soft porn, modernist design and the viscous seductions of paint, Patterson’s work often evokes both melancholy and desire. Here, Noah Simblist talks to him in his studio about his current paintings. They began by discussing the problems with working with appropriated imagery.

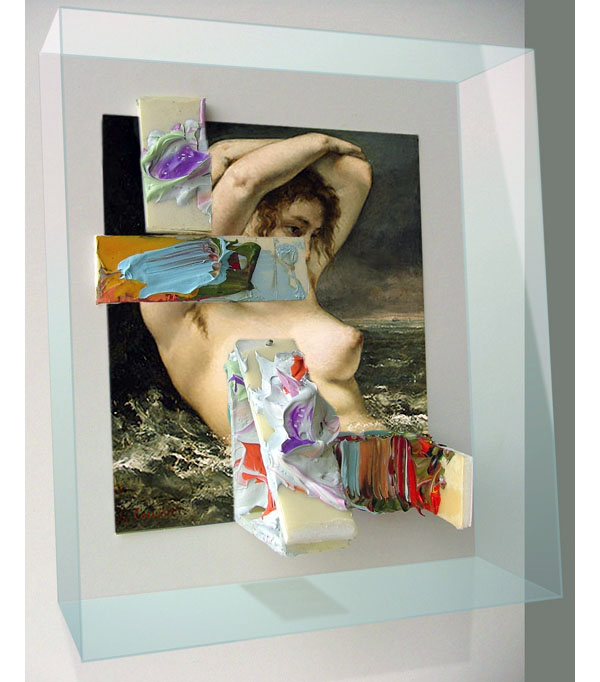

Richard Patterson: There’s so much shit to worry about. That’s what has sort of driven me to generate my own imagery rather than referencing other material because unlike in Germany where everything is seen as fair use, everywhere else it’s not. So it’s a very prohibitive time, you can’t visually comment on the world now in a satirical or ironic way without getting permission first. So, I got good enough in Photoshop where I started realizing that if you already know how to paint and draw you can actually generate stuff from scratch without sampling it.

Noah Simblist: The breasts in the Doge painting are from scratch?

RP: They are absolutely from scratch.

NS: Really?

RP: I decided to adorn these dancers with these slightly crazy, slightly cartoon breasts. And then Bellini’s Doge of Venice appears in the middle. There was a lot of power invested in this one person who is basically elected. I think of him as this benevolent type of prince. That’s not why I did it, but you know, he seems a little like the local collector Howard Rachofsky.

NS: The Doge of Dallas.

RP: The Doge of Dallas and all the breasts you know. These are my fake breasts.

NS: The Dallas fake breasts.

RP: These are the people that inhabit galleries. It’s also like Picasso. It’s the fear of impotence and death and the younger fertile woman you know. Also I think its ridiculous, it’s got a cartoony kind of dumbness to it.

NS: You have said that these paintings are not meant to be purely ironic like the way that Jeff Koons uses appropriated imagery for a sly commentary on contemporary life.

RP: Koons is all about irony. But, there is a melancholy and genuineness, a specific mood in some of my paintings that isn’t there in Koons. Koons is all about the tedious stuff about consumerism.

I think that the American understanding of irony is where you say, “I really like your new sweater…not” My understanding of irony is from English culture, which is entrenched with irony. If you had your country blown to bits in living memory or you parents memory and you’ve seen your country change…We used to have this massive empire and I was brought up to believe that there was still this kind of Great Brittania type shit and then it is so clearly dwindling. How can you not be ironic about the fact that Hitler bombed the shit out of your country. That gives you a kind of cultural irony that is so, English. English culture is shot through with being invaded and assimilating new cultures through its history and then developing a sense of humor about it.

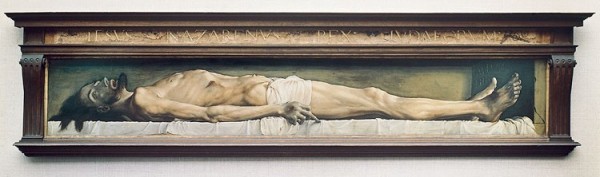

NS: That’s interesting. What you’re talking about relates to our standard history about Dada and Surrealism that was about uncanny contradictory things being put in one place together. The idea of something that seems both funny and horrific at the same time was coming out of World War I or World War II, by people that were being confronted with the most bizarre circumstances. During the Blitz you’d see a burning building and abject destruction but people that lived next to that building still had to go about their daily lives by going to work, doing laundry and grocery shopping. So you have this kind of banal thing that is also epic at the same time.

RP: Well I think so much gets lost in translation and you know I think that there is a default setting that the Brits have that is so self-deprecating, self-questioning, self-doubting and America since 9/11 is going to be more ironic, and maybe intimate as well.

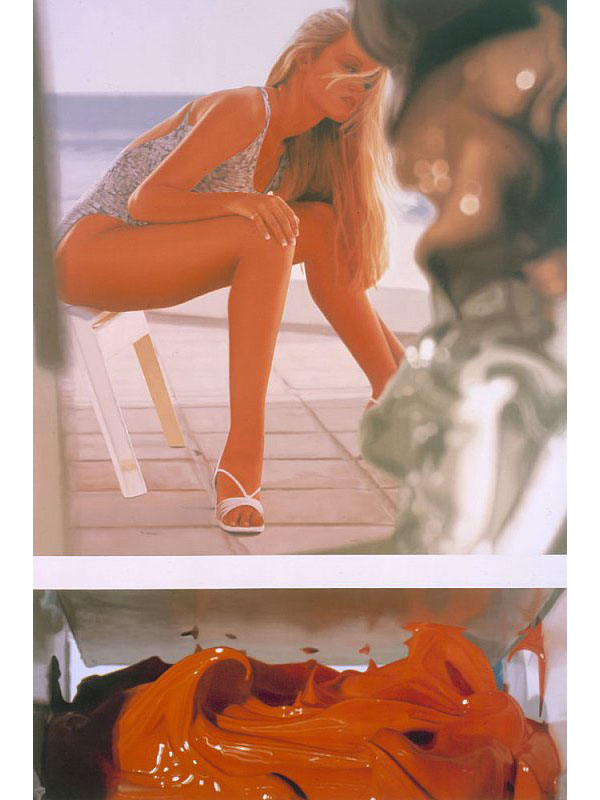

If I did a painting of whatever it was that I was painting – cartoon breasts or something – it doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s what I wanted to see. In fact, it was often the opposite. I wasn’t painting Spice Girls because I thought Spice Girls were great. Some people say, “You sort of like the bikes and the tits right?” It’s a difficult question cause I do. The red one is a collectible bike that raced in Europe in the sixties and I do like them but the irony is for me to put them into paintings is incredibly bad.

NS: Does this connect to an idea of taste? Is every painting or every work an artist makes an expression of their taste? Similarly, like the curator acquiring something for their museum. Is that an expression of their taste? It seems like you’re saying the opposite. These aren’t just expressions of your own likes or dislikes.

RP: Yeah, taste is a real good thing to talk about cause it’s the most objective thing. It’s the thing that sounds most nebulous, maybe least important and maybe it’s the most important thing. Because in term of these images, not only are they reproduced very, very carefully, when it comes to actually painting them, but a huge amount of work has gone into trying to balance colors and compositions to make them. I mean they are quite classical; the reason I think it looks so weird is because it’s a very classical painting in an age that isn’t. So its difficult to find a context for them. It’s like to trying to talk about Schoenberg to the MTV generation. Is it possible to paint a bright red Toyota Tacoma truck with these funny bulges, with wheel arches that are really quite ugly that Toyota described in their press release as “muscular bulges” that didn’t look like muscle at all; they looked like rolls of fat around someones middle.

NS: I read something recently about a coup within Toyota where the CEO who was responsible for bringing out these big trucks and big SUV’s and replacing their traditional model of having smaller fuel efficient cars with these bigger things because it was feeding the American appetite was publicly chastised by Toyota’s grandson. They fell into a lot of the same problems that the American car makers did. He publicly rebuked him for being greedy and too connected to the dirty obsession with power and size that Americans have and throwing away all the virtues that the company was founded on.

RP: I wrote a piece for Glenn Fuhrman’s show at the Flag Foundation in New York, about something connected to this. Glenn has the Back of the Dealership painting. The title was an obvious pun on paintings being back at the art dealership. But it was also genuine. I kept going back to the Toyota dealership on Sundays to take a look at the trucks when there was no one there. But there was always some salesman, who seemed to be on Sunday duty at the shop trying to sell you a truck and they never knew as much about the truck as I did. They’d tell you it was an eight cylinder truck and it was a six cylinder truck. They never seemed to know what they were talking about. And, then somehow oil was getting more expensive.

I was already locked into that syndrome and I was kind of aware of it and built credit by spending money I did not have just to be taken seriously in America. Politically you don’t have any power unless you’re in debt. So basically all money is debt, and if power is money you can say that power is debt. So owning one of these fucking trucks was contributing to the economy and it was also your license to be fully American. It was clearly fucked up. I think that’s why I wanted to move here. And now of course it’s going to look too obvious because its going to look like its about the economy. If it’s ironic, its going to be about trucks or the economy or something. But I was actually experiencing it as a foreign national in a slightly different way than probably ordinary Americans would.

Postscript: While the above excerpts from a conversation with Patterson covered the complex layering of conceptual tropes in his paintings, the discussion frequently turned to larger issues about living and working in a regional American city like Dallas. Patterson has taken a leading roll in recent years to bring his experiences of participating in an emerging art community in London – which in the mid-80’s was not the art center that it is today – to bear on Dallas. But he also continues to show his work internationally. Most recently he is participating in “Size Does Matter,” an exhibition curated by Shaquille O’Neal which opened on Feb 19 at The Flag Art Foundation in New York.