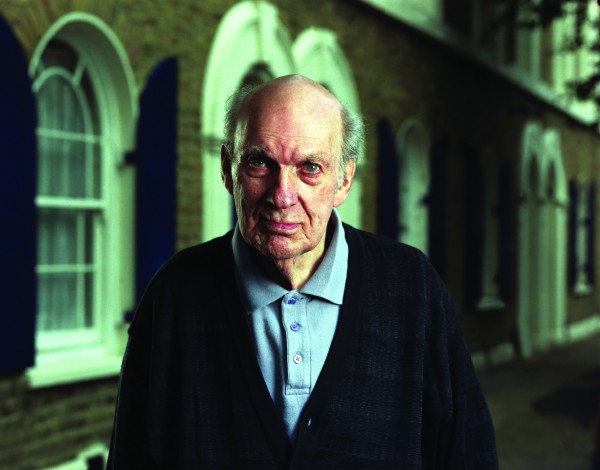

As a painter of political ideas—and, often, the grotesque and cruel—Luc Tuymans is a historian of images that appear banal but reveal sinister workings: colored blobs are actually disembodied eyeballs; a bare room with flattened perspective is the site of uncountable murders; a limp cloth turns out to be the emblem of a growing nationalist movement. His first U.S. retrospective, a mid-career survey now at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, is installed in chronological order, rewarding the viewer with a sense of how his ideas developed for each series. To mark this notable event, Mr. Tuymans conducted a personal tour of the galleries, illuminating his process and the themes behind each work. He concluded the tour with the remark, “I am not interested in having power. I am interested in looking at power.”

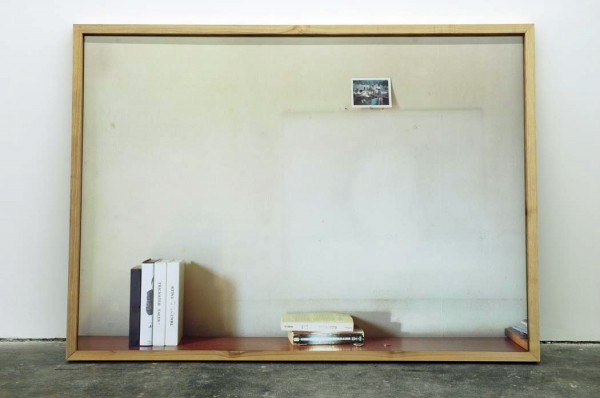

La correspondance (Correspondence), 1985. 31.5 x 47.5 inches (80 x 120 cm). © Luc Tuymans. Image via the excellent Luc Tuymans, edited by Madeleine Grynsztejn and Helen Molesworth, ISBN 978-1-933045-98-6.

“I stopped painting from 1981 to 1985 because it became too suffocating and too existential. And somebody by accident shoved a Super-8 camera in my hands and I started to film. And then I came back. Making images is important in the sense that you need distance.”

“This was the first painting made after the film adventure [above]. And it’s actually one of my most conceptual works, and it’s based upon an anecdote. The anecdote is from a Dutch writer who was stationed in the Dutch Embassy from 1905 to 1910. And he didn’t have enough money to bring his wife over to Berlin. And in those days you had the grand cafes with very bourgeois interiors, and also postcards taken of them. So every time he went to eat in such places he bought a postcard, and with a red pencil he crossed out the table at which he had eaten, and he sent it to his wife during the duration of five years. So that’s why it’s called correspondence. It’s also the idea of persistence, and homesickness without an end.”

Die Wiedergutmachung (Reparations), 1989. 17.75 x 21.625, 15 x 17.75 inches (45 x 55, 38 x 45 cm). © Luc Tuymans. Image via the excellent Luc Tuymans, edited by Madeleine Grynsztejn and Helen Molesworth, ISBN 978-1-933045-98-6.

“This is something I saw on television. It’s called the Weidergutmachung, and it’s about the woman who made the documentary, it was made in ’89, which is when I saw the documentary on the West German television. It was quite an interesting documentary because Weidergutmachung means the pay-back system towards the people who suffered in the concentration camps…this time not the Jewish people, but Gypsy twins on which the German doctors in the concentration camps had experimented. These people were never paid back because the guy who was actually responsible for the whole situation of the repayment was also a doctor who himself experimented on them during the times he was working in the concentration camp. When he dies off in ’83 in his bureau drawer, the woman who was making the documentary found contact prints of disengaged eyeballs and hands. So this is what I saw on the television screen. It was such a poignant element that I turned it into a more organic imagery.”

Gaskamer (Gas Chamber), 1986; oil on canvas; 24 x 32 1/2 in. (61 x 82.5 cm); The Over Holland Collection. In honor of Caryl Chessman; © Luc Tuymans; photo: Peter Cox, courtesy The Over Holland Collection

“The most problematic painting that I ever painted—that I ever will paint as long as I live, probably—is the Gas Chamber. The Gas Chamber was derived from a visit to in Dachau where you have a real gas chamber and not a replica. And I stood in it, and I made a watercolor when I visited it, and for years this watercolor was on the floor of my studio, which made the color of the paper yellow. And I also made it on a frame that is deliberately not straight. It’s a metonymous image, because without the words of the title it would be completely without effect, it would be just a painting. Nevertheless, it shows the triviality of that type of horror. At the time of its use, it was masked as a place where you could get a shower. All the elements of perspective are taken out, in order to get to this feeling of claustrophobic existence. I mean, a lot of times the Germans say, ‘We can’t deal with that type of history as the Holocaust,’ but I’m not agreeing with that, it is part of the culture… This remains a very difficult and ambiguous painting.”

The Flag, 1995. 54.375 x 30.75 inches (138.1 x 78.1 cm). © Luc Tuymans. Image via the excellent Luc Tuymans, edited by Madeleine Grynsztejn and Helen Molesworth, ISBN 978-1-933045-98-6.

“This was from a show about Flemish nationalism in my hometown, where at that point (luckily not anymore) there was the biggest concentration of the right-wing political party called the Flemish Bloc. So I thought I would start with their icons. This is the Belgian lion. The Belgian lion normally is a lion on a yellow backdrop with red claws. To enlighten you about the history of Flanders is going to take us very long, because it’s a long story to begin with, but anyway, to give you an idea…During the first world war, all the officers were French speaking. This meant that during the First World War a lot of Belgian people died in that war, millions of them. The people who were the soldiers, the foot guys, they were all Flemish; there were huge massacres, because when the officers would say a gauche [French: left], they would go right, into the machine fire. In between the two world wars there was a closeness in terms of culture to the German culture, more than to the French culture. And that ended up in a collaboration with the Germans. So a very difficult situation. That’s why you have a lot of marriage trouble, which I also witnessed. My mother was Dutch, they were in the resistance. My father was the Flemish side, they had collaborated. At dinner, when I was five years old, this explodes by the accidental showing up of a photograph of the guy I was named after doing the Hitler salute. You can imagine the whole situation. So what you can see here is the Flemish lion, and I just made a watercolor of it, and then I crumbled it together, and then pinned it on the wall. And then I did something I had never done before, I took a Polaroid of it, and it was such bad quality that it totally deleted the imagery, which is actually beautiful I think. And this was the first time I used Polaroid as a device to derive imagery.”

Ballroom Dancing, 2005; oil on canvas; 62 1/4 x 40 3/4 (158 x 103.5); San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, fractional and promised gift of Shawn and Brook Byers; © Luc Tuymans

“This was painted out of my disgust with the Bush legislation. The first idea I had was this: I was thinking of this element of regression in American society in those days, going back to an open form of conservatism, and therefore Fred Astaire, Ginger Rodgers. Ballroom dancing. So then I was on the web browsing, trying to find more contemporary imagery, and in 2005 there was the Texas Governor’s ball, this is the Texas seal, the woman swings her head out, this guy is the epitome of well-behaved and whatever. And on the other hand, this is an image that’s really classical, I really loved doing it…”

The Secretary of State, 2005; oil on canvas; 18 x 24 1/4 in. (45.7 x 61.5 cm); Collection the Museum of Modern Art, New York, promised gift of David and Monica Zwirner; courtesy David Zwirner, New York; © Luc Tuymans

“…Then, one of my best friends who used to be the Minster of Foreign Affairs, made a remark of Condoleeza Rice—I was in a bar, reading this in a newspaper—there was a day Condoleeza Rice came and visited our country, and he said something like, “She is very intelligent, and she is not unpretty.” And this sexist remark led to my idea of Condoleeza Rice. The interesting point is that she is depicted not to be judged, she is depicted with great determination. At that point no one knew what the woman was going to achieve.”