Better Off Dead

L.A. Expanded: Notes from the West Coast

A weekly column by Catherine Wagley

Jeff Sonhouse. Installation view (from left to right): "Papi Shampoo," Mixed media and oil on fiberboard; "Mateo Manhood aka Buzz Kill," Oil on fiberboard; "Decompositioning," Mixed media and oil on fiberboard; 2010. Courtesy Martha Otero.

Leslie Hewitt’s Grounded is a staircase that goes nowhere. I saw it at the California African American Museum last winter in After 1968: Contemporary Artists and the Civil Rights Legacy, a show about the ripples of the year a jailed Huey P. Newton said “we’re hoping the master dies” and Joan Didion experienced socio-politically induced “nausea and vertigo.” All artists included were born in the last 42 years, after 1968.

Because I walked between the wall label and Hewitt’s sculpture twice, the gallery attendant asked if I understood the art. Caught off guard, I asked, “Do you?”

She said she did, then told me what was more or less a parable: back in the ‘60s, my father and hers might have worked for the same company, lived in company houses, and been offered tools to refine these houses. To get their tools, they might’ve stood in lines, my father in the “whites only” line, hers in the line for black employees. Mine might have gotten one set of tools, hers another. Her father’s wouldn’t have fit together correctly and he might have complained to the bosses, but they would have shrugged, and said, “Those black people never get it right.” Then he would have done what he could, building the pyramid-like, non-functional staircase with its angled railing.

Though weirdly precise, this story sidesteps one key fact: Hewitt’s Grounded is the work of someone who wields the “wrong” tools like a pro. It turns non-functionality into a cool exercise in stylish lyricism, a way to control the way you’re being controlled and an f*** you to the powers that be.

Jeff Sonhouse, "Mateo Manhood aka Buzz Kill," Oil on fiberboard, 16 x 13 ¼ inches, 2010. Courtesy Martha Otero.

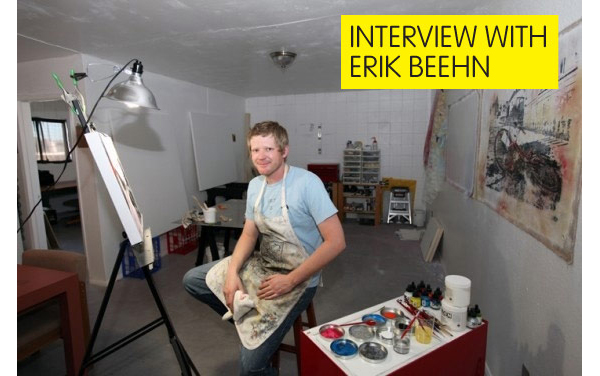

Jeff Sonhouse’s paintings are stylishly controlled, too. On view at Martha Otero Gallery, the cameos of masked men indulge in pattern and texture. The subject of Gravity’s Lawlessness, for instance, wears a lemon and ultramarine diamond print suit, with neck and face masked to match. In Maskulinity Resuscitated, the subject has steel wool curls, and wears pinstripes and oversized cream-colored medallions that fall past the painting’s edge. All the other figures stay within their designated rectangles, however. They’re posed head-on like Van Eyck’s and their dandyism feels like it’s festering on the panel surfaces.

This is Sonhouse’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles, surprising since his debut at New York’s Jack Tilton Gallery took place eight years ago, but also fitting. His work has a New York ethos. His men could live in Brownstones and feel at home wandering through the frames of Looking for Langston (if the film were in full color, that is). The show’s title, “Better off Dead,” said the Landlord, has a New York feel to it as well. It’s hierarchical and violent but also vague.

Jeff Sonhouse, "Our Savior," Oil, gouache, watercolor, matches on paper, 22 ½ x 14 inches, 2010. Courtesy Martha Otero.

The eyes of the figures, peeking out of their various masks (or anti-peeking, in the case of Papi Shampoo, who has mirrors in his sockets) are opaque in a way that feels like refusal, maybe a refusal to acknowledge to the amorphous “Landlord” but more likely a refusal to acknowledge vulnerability of any sort.

There’s a Jesus motif in the show, but it’s not Papi Shampoo with his purple cloak and Nazarene-worthy hair or the protagonist of Decomposition with his large, shepherding hands that play the role of the deliverer. In Our Savior, a small work on paper, a slight man stares out of a rough-cut geometric mask with eyes that are warmer than those of the other figures. The matches that make up his hair leave a halo of soot around his head. He’s turned the “tools” of convention–suits, squares, matches–into vehicles for passive aggression and seems to be toying with letting go of his “stylish control.” Maybe he’ll self-combust, or lurch forward off the picture plane. If he does, the tension that holds Sonhouse’s show together would collapse, and it’s hard to predict what would happen next.