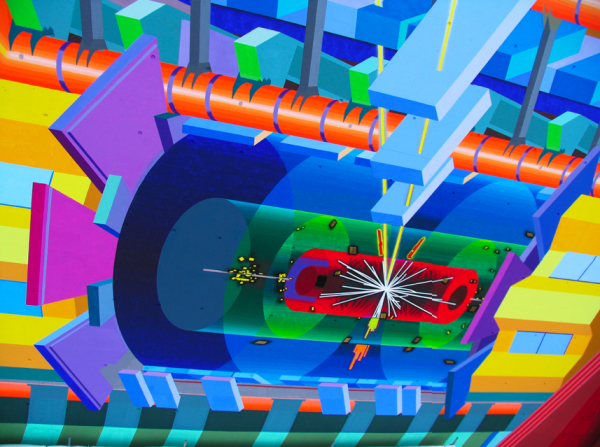

The twentieth century has provided a plethora of methods to communicate quickly to the masses, and it is becoming increasingly rare to find anyone taking the time to write a handwritten letter, much less create a large-scale public mural to share ideas with the public. However, for almost all of human history, wall paintings have served as one of the most effective ways to chronicle the events and progress of our time. Artist Josef Kristofoletti has tapped back into this method of communication and it has led him to some amazing places. From the gymnasium of his former high-school to a year long road trip around North America with the Transit Antenna artist collective, Josef’s desire to paint in public spaces has kept him moving. Perhaps the most impressive of these large-scale murals took place at CERN, the world’s largest particle physics laboratory, situated in the Northwest suburbs of Geneva on the Franco–Swiss border. There, Kristofoletti created a four story mural of the ATLAS particle accelerator, directly on the walls that contain the actual structure. Since the completion of the project just a few months ago, I’ve been dying to talk with the artist about his experience of seeing the world’s most ambitious laboratory, as well as the completion of his most impressive mural to date.

Seth Curcio: So Joe, you recently had the unique opportunity to do an artist residency of sorts at the famous CERN, the European Organization of Nuclear Research on the boarder of Switzerland and France. You had the honor of being the first artist invited to produce an original work of art for the organization. Tell me what projects led up to this invitation and how did the world’s largest and most advanced scientific laboratory learn about your work ?

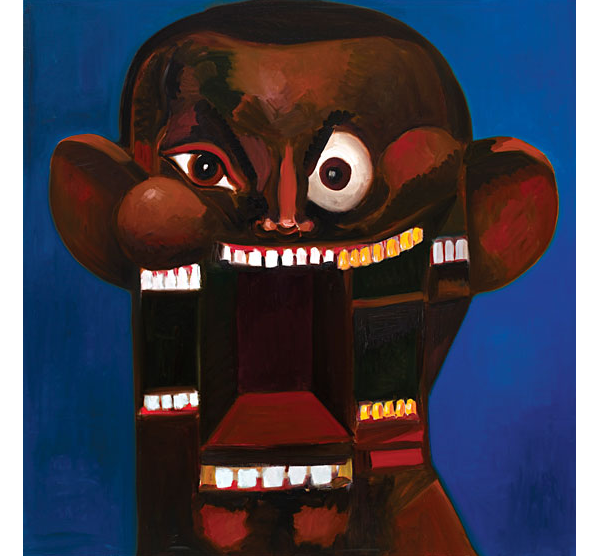

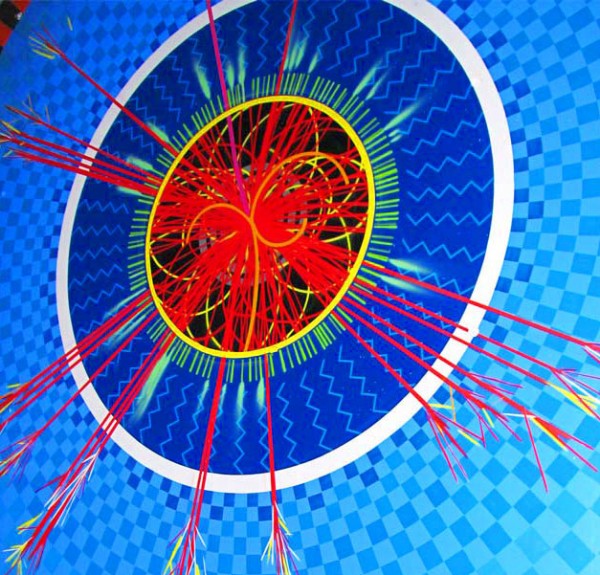

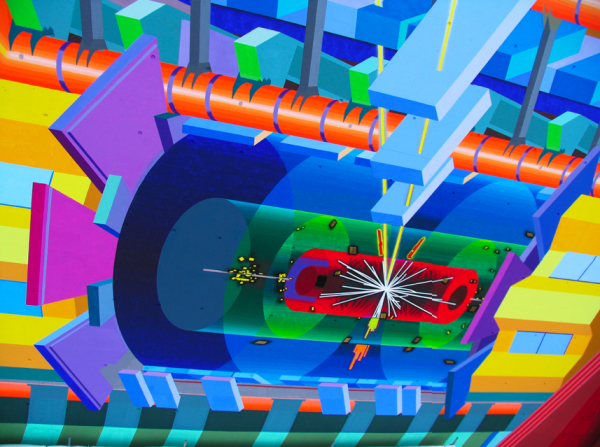

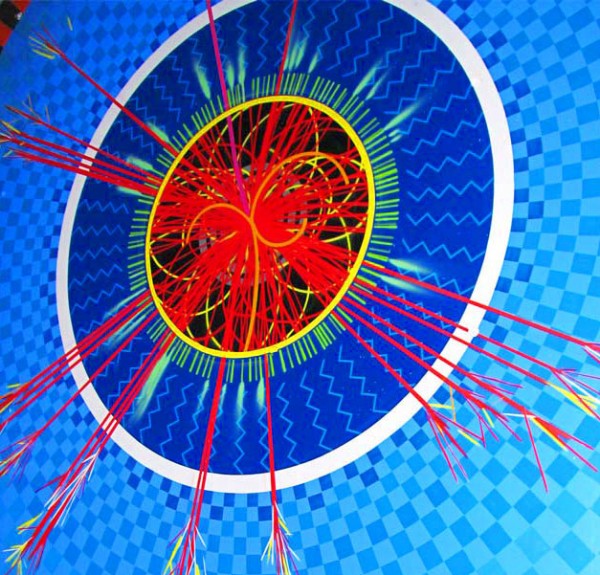

Josef Kristofoletti: In 2008, I made a painting for a two person show with my friend Matt Phillips at Redux Contemporary Art Center. Matt and I had some conversations before the exhibit about what we wanted to show. We talked about the origin of the universe and dark matter, then I decided that I would do something related to CERN. I painted a mural of ATLAS, the largest of the CERN particle detectors. I tried to make the mural scientifically accurate, based on the schematics available on the CERN website. After the show opened it got a little bit of press and a month or so later I got a call from Claudia Marcelloni, the photographer and outreach coordinator for the ATLAS experiment. She told me that they had seen photos of my mural and asked if I might be interested in doing something on location. I couldn’t believe it at first, it just sounded really strange over the phone. We set up a time for a meeting with some of the physicists and I booked a flight to Geneva that same day.

SC: Once you arrived at CERN, the officials gave you a tour of the facility, allowing you, an artist, unprecedented access to such highly restricted laboratories. Tell me a little about what you saw and how it turned into inspiration for the gigantic painting that eventually came to be?

JK: From the airport the CERN shuttle picked me up and took me right inside the lab’s main building. I met with two incredible scientists who work there, senior physicist Michael Barnett who is the head of the Particle Data Group, from Lawrence Berkley National Labs, and Neal Hartman, who engineered the innermost part of ATLAS, the pixel detector. It was a great meeting because they were as excited to talk to me about art as I was in finding out more about super symmetry. We talked about Egyptian sculpture and cinema. Neil has since left his position at CERN to attend film school in London. Anyway, they gave me a tour of the ATLAS facilities and we looked at some of the walls that I could potentially work on. By that time the detector, which is over 90 meters underground, was completely closed off to visitors and gearing up for the cool down process. Before collisions can start the entire 27 km tunnel is chilled with liquid helium to a temperature than is cooler than outer space. As we were talking about the possibilities of the project, my guides realized that I had to see the actual detector in person. After they made a few phone calls, and I started going through the most high secure checkpoint I have ever seen. The workers go through a complex biometric security system that includes a retinal scan. They all wear a dosimeter that measures radiation levels and there are plenty of safety warning labels on everything. We took the elevator down, then stepped out to look at the beast. There were a few men inside the detector doing some last minute work, but they were reduced to ants by huge size of its metal parts . It was sublime.

SC: This sounds amazing! I bet you never imaged in a million years that your research and project about ATLAS would eventually bring you into the exact laboratory that you studied for the mural at Redux Contemporary Art Center. I’d love to hear about some of the technical obstacles that you faced when creating the work, such as the time line needed for creating such an ambitious work, how you selected your subject matter, and dealing with extreme weather on the Franco-Swiss border. I even heard that you became a dad over this whole process. It just seems larger than life, both literally and metaphorically.

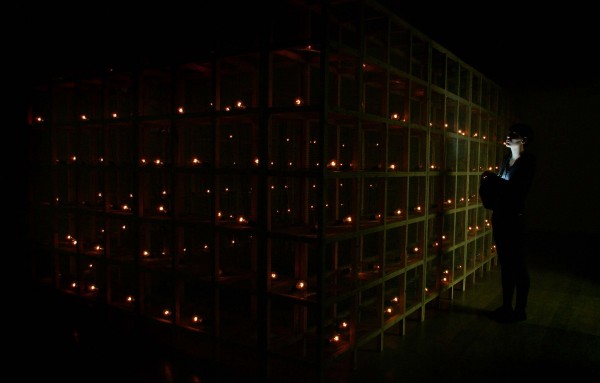

JK: I couldn’t get everyone to agree on the location that I wanted for the mural. I really wanted it place directly over the detector itself, and that alone took months. By the time that process was accomplished I had to start right away even though there was no funding for the project yet. I had charged the ticket to a credit card and flew back to Geneva from the United States. My third day there I met a side show performer named Stephan who lived by the train station and offered to let me sleep in his squat. He has this act where he can eat and swallow lit cigarettes. Stephan helped me stay sane for much of the project. There were so many security and safety issues at CERN that every day new problems came up. I had to go through safety courses to get clearance to work on the site and to use the Nacelle lift, which is the machine that was used to assemble the detector itself. I could not afford any assistants because it would have taken many more months of paperwork and training. I worked through French and German interpreters on many of the logistical issues and some of the safety classes. By the time I was able to touch paint to the wall it was October and getting colder every day. One day I couldn’t feel my hand any more and I realized that I had to face reality and come back the following year. I was able to finish the smaller of the two walls by mid November and had to return in June to continue. Halfway through the painting the whole operation was stopped by one of the electrical engineers in charge of safety. I was working right over the transformers and he said that in case of an accident the power supply would be jeopardized to the whole experiment. That stopped me until further security measures were dreamed up.

Every once in a while one of the physicists would confront me, very seriously, about how some part of the detector was not drawn properly. But, I respect that because for many of them this is a life’s work. Some have been there for twenty years going over the smallest details thousands of times. The whole detector is exactly precise to within one millimeter. I tried to explain to them that I was just making a painting. From up it the air I could see Mont Blanc just to my right, and the Jura mountains to my left. When I started on the proposals I found out that my wife was pregnant. My son Daniel was seven months old when I finished the mural. A lot of what has happened I can’t put into words, its been both shocking and beautiful. While I was at CERN I saw a lecture by Stephen Hawking. He was one of my childhood heroes. The first slide he showed said: ‘Why are we here? Where did we come from?’

SC: That all seems like such a feat in itself, not to mention the fact that in the end you created an amazingly ambitious mural that lives up to all the magic that is happening inside the facility. So now that you are back in the US, what kind of projects are you working on, and what do you have coming up?

JK: Just before I came back to the US I went to Fame Festival in Italy and it was one of the most amazing art exhibitions that I have ever seen. It was so cool to see huge paintings by BLU and the other artists, I found that very inspiring. I’m really obsessed with large-scale paintings on walls and I love that the street art phenomenon keeps exploding all over the world. My next big project, which I’m super excited about working on, will be doing something for the Olympics. Details on that project to come…