Collectors’ Stage: Asian contemporary art from private collections

Subodh Gupta, Everything Is Inside, 2004, Taxi and bronze, 276 x 162 x 104 cm, Arario Collection. Image courtesy of the artist and Arario Gallery, Cheonan, Seoul.

Not too long ago, I spoke with Howard Rutkowski, formerly of Sotheby’s and now director of Fortune Cookie Projects, intending to satiate my curiosity about art auctions and art dealing. While he probably scoffed at my naivety, he candidly said to me, “Plunging into the murky business of the art world is akin to swimming with the sharks. There’s a delicate dance that takes place between buyers and sellers.” There seems to be very little disagreement in those sentiments in Rutkowski’s diplomatically crafted comments; they are in fact, echoed with gusto ad naseum in many recently published books about art dealing and collecting, where vitriol, fake kisses and nefarious sleights of hand are as commonplace as a trip to the supermarket in a world resolutely disconnected from reality.

“The nature of the art business is that it’s filled with pettiness and jealousy. There’s little mutual respect…everyone is insecure about their accomplishments, which often leads to a great deal of bad behavior to disguise the truth,” writes Richards Polsky with remarkable honesty in I sold Andy Warhol (too soon). “It used to be all about the art world: visiting artists in their studios, socializing with collectors, and hanging out at art fairs with your fellow dealers. Now it was all about the art market.”

It is a commonplace but also a shrewd observation. A more accurate description of the “art world” these days must extend beyond appreciation and connoisseurship to the capitalist maze system of production and consumption in whose perilous waters artists, dealers, collectors, museums and galleries navigate. With the dissolution of cultural and commercial barriers, art criticism and appreciation face possible relegation to serve as mere adjuncts to the main business.

Ai Weiwei, Table With Three Legs, 2007, Table, Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), 117 x 115.5 x 115.5 cm, Collection of Mr Qiao Zhibing.

Running parallel with Art Stage Singapore – an international art fair that ended 16 January 2011 –, Collectors’ Stage: Asian contemporary art from private collections suggests that public exhibition spaces can get caught in these lively but fraught relationships. As a show created by a public institution, Collectors’ Stage engages in the meeker, mellower side of art-for-education purposes, positioning itself alongside Art Stage insofar as it could remain a neutral, fringe program while pinching some of the excess stardust from the highbrow glitz and glamor of its dominant partner. The show is intriguing in its bypass of a typical educational program that is de rigueur in many public art institutions’ exhibitions, lacking a certain insistence of pedagogical material and the usual contingent mix of critical thinking and art historical discourse. Drawing from the rich and varied coffers from private collections in order to parade the sheer diversity of Asian art lying in private hands, the exhibition triumphs the astute discernment and emerging intelligence of the collectors, while implicitly acknowledging the opaque (and potentially difficult) web of money, prestige and aesthetic (and monetary) value that exists between artists-as-producers and consumers.

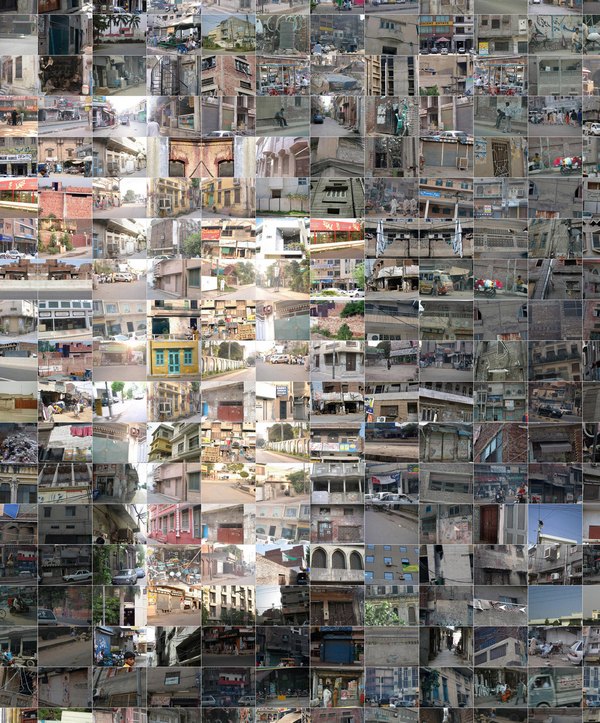

Rashid Rana, Desperately Seeking Paradise, 2007 – 08, C-Print + DIASEC, stainless steel, 300 x 300 x 300cm, Collection of Amna and Ali Naqvi. Image courtesy of the artist.

The result in this instance, is a close-knit, reciprocal and mutually beneficial relationship that emerges when private collections surface in public spaces. Collections that rest in a museum for any period of time cannot help but gain public exposure (or notoriety); both collectors and artists benefit from the increased media scrutiny – despite the sort of press it might receive. An institutional display thrusts upon an artist much valued affirmation and recognition while potentially providing them a step-up in the elaborate system of critical reception and endorsement, and collectors themselves are validated by their purchasing inclinations and intellectual taste. Depending on the choice of works, the museum in turn, receives accolades for its program and its audacious bid to entertain.

The repercussion of this agenda however, is the compromise of the works’ engagement with the space in which they are presented and it is seldom that their content or meanings are found in dialogue with its surroundings or its viewing public. Despite the standing argument that the gallery’s white spaces are contested territories that actively influence the reception and meaning of art, space in Collectors’ Stage is utilized as vacant zones housing the sheer size of some installations, and the works are assembled and administered rather than didactically curated.

It is still entirely possible (and perhaps even necessary) to enjoy the works as individual entities. Many of the artworks are jaw-dropping and materially accessible, open to non-specialist viewers unfamiliar with art theoretical concepts. Thematically grounded in issues innate to contemporary Asian art and familiar to Asian viewers themselves – the dichotomy of embracing progress and observing tradition, political farce, the burden of modern life, urban sprawl –, this brave new world of the Asian aesthetic is constantly lamented and paradoxically praised.

Shen Shaomin, Summit 2009 - 2010, Installation, Dimensions variable, Osage Art Foundation Collection.

Chinese artist Shen Shaomin’s Summit (2010) challenges the annual G8 Summit where world leaders meet to discuss global political and economic events, offering instead, a hypothetical meeting of the most influential communist leaders in history (Fidel Castro, Vladimir Lenin, Mao Zedong, Kim Il Sung, Ho Chi Minh) in the light of the recent global financial meltdown and the apparent failure of capitalism. Shen’s Summit brings together – if never in history, then only in museum (or mausoleum) space – resin-silica-gel constructed cadavers laid out in a pentagon formation in crystal coffins reflecting their nationalities, with the exception of Fidel Castro who lies on the brink of death. With hushed and repellent awe, we are asked to venture into ideological black holes; has capitalism juggernaut’s also finally come to a halt as spectacularly as socialist ideology waxed and waned in the twentieth century?

Subodh Gupta’s Everything is Inside (2004) is India’s iconic yellow Ambassador taxi sinking under the weight of its load, reinforcing the eternal themes of travel narratives: dislocation and relocation within the rural and urban spheres as consequences of aspirations and the relentless quest for prosperity. Prizing the abstract and the multi-dimensional is Rashid Rana’s Desperately Seeking Paradise (2007-8), a sculptural work that questions the act of representation and perception through the distortion of visual sequences of Lahore. Hu Jieming’s 100 years in 1 minute (2010) deconstructs the “grand narrative” of history by piecing together fragments of the past century’s momentous events in various combinations within 1 minute, consequently presenting infinite possibilities of historical trajectories that could have been.

Such works provide a dynamic summary of contemporary Asia: anxieties of geopolitical and socio-cultural changes that quite nicely form the thematic bedrock of Asian artists. They are deemed worthy of visual consumption and are called “great” because of the existence of a complex thread of validation from multiple sources. Collectively, it is not an automatic cause for celebration. With virtually unchallenged reviews and effusive praise, where then, is the place for dissenting voices and criticism amid these potentially intellectually stifling accolades? Where is the counterbalance of censure and soul-searching that has made these works what they are? Like Shilpa Gupta, I itch to start the blame game.

Shilpa Gupta, Blame, 1999, Installation with plastic bottles, Dimensions variable, The Lekha and Anupam Poddar Collection

Collectors’ Stage: Asian contemporary art from private collections is organised in cooperation with the first edition of Art Stage Singapore 2011, the newest international art fair in the Asia Pacific. The exhibition is presented at the Singapore Art Museum, and two off-site venues, ARTSPACE @ Helutrans and Tanjong Pagar Distripark. It will be on view until 17 February 2011.

NS: You have said that these paintings are not meant to be purely ironic like the way that Jeff Koons uses appropriated imagery for a sly commentary on contemporary life.

NS: You have said that these paintings are not meant to be purely ironic like the way that Jeff Koons uses appropriated imagery for a sly commentary on contemporary life.