Recent advancements in technology such as Google Earth and street-view, has given anyone with a computer and an internet connection the ability to collapse time and space. It is easy to sit in the comfort of your home and within just a few seconds, virtually place yourself anywhere in the world, that Google has imaged. This uniquely 21st century way of seeing may be relatively new to the masses, but there is no doubt that similar advancements were made years ago for military purposes. From the birth of photograhy, man has learned to “see with machines.” This concept is a crucial part of Trevor Paglen‘s research in art and experimental geography. Paglen recently presented a new series of images, and video, in an exhibition titled Unhuman on view now at Altman Siegal Gallery in San Francisco. I recently spoke with Paglen about photography and art history, aesthetics and the politics of watching that which watches us.

Trevor Paglen They Watch the Moon, 2010 / Courtesy of Altman Siegel Gallery

Seth Curcio: Trevor, your practice is centered in both experimental geography and art-making. Often the two collapse into one. Did your interest in geography develop concurrent with your interest in art-making? Or, did one come before the other?

Trevor Paglen: I’ve been an artist my whole life – much longer than I’ve been a geographer. In the mid 1990s, I started doing projects that had a strong relationship to landscape and the politics of visibility. While earning a MFA in Chicago, I became frustrated by the limits of traditional art theory, which mostly comes out of literary criticism, and wanted to find a more expansive theoretical language that could account for things like economics, politics, materiality, and so forth, in addition to questions of representation. Geography theory, I found, was incredibly powerful and flexible: it provided me with a way to think about cultural production in a much more powerful way than what I’d found in art and representational theory. So, I ended up moving to Berkeley and doing a PhD in geography.

Trevor Paglen: Unhuman Installation View/ Courtesy of Altman Siegel Gallery

SC: It’s interesting to know that you began making art long before your interest in science. In much of your work, there are strong references to art history as well as the history of photography. Those histories are intermingled with political and scientific concerns, allowing much of the work to function on multiple levels simultaneously. There are obvious references to Abstract Expressionism in works such as The Fence (Lake Kickapoo, Texas) and Untitled (Reaper Drone), as well as specific references to the history of photography in the works Time study (Predator; Indian Springs, NV) and Artifacts (Anasazi Cliff Dwellings, Canyon de Chelly). How do you feel these art historical references operate in the work, and what insight do they provide the viewer?

TP: Absolutely. There are all sorts of reference and nods to various art-historical moments and works, and references to specific historical photographs and gestures. I constantly use those references in a number of ways. With those references I want to ask “150 years ago, for example, a photographer looked at a particular place and that act of looking and photographing, at that particular historical moment, said a number of things about that historical moment. What happens when we try to see the same place now, and what might that act of seeing or photographing tell us about our particular historical moment?” The same is true for the references to various representational modes: “What,” for example, “does abstraction mean now? What, if anything, from that particular way of representing a historical and cultural moment, is relevant to our own contemporary moment? Why? And how?” For me, these sorts of historical references act as guide-points that we can use to understand how to see the world now, which is ultimately what I’m interested in.

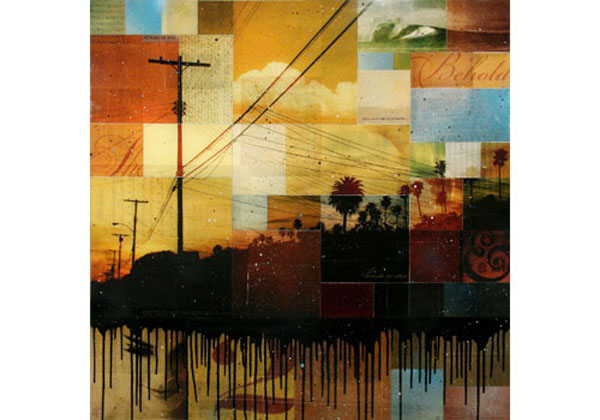

Trevor Paglen Untitled (Reaper Drone), 2010 / Courtesy of Altman Siegel Gallery

SC: The notion of seeing remains consistent in your work. As you mentioned before, this idea can be explored through the use of photography or by referencing specific moments of art history, when considering how other artists have seen the world and then represented that view in their work. Beyond these methods, much of your work is also investigating technology that is designed to see us, but not be seen. I find it interesting that the main way you shed light on these objects is to track and photograph them yourself, further reinforcing the idea of seeing. It seems that you are actively engaged in watching that which watches us. How do you feel about this cyclical processes?

TP: I think that there is a little bit of any irony in the act of “watching the people who are watching you” here for sure, and it’s certainly something that I’ve developed into a sub-theme quite explicitly in some works. But overall, I don’t think that particular dynamic is something I’m categorically interested in. That reading seems to emphasize the “surveillance” aspect of the work too much, and I’m actually not particularly interested in surveillance, per se. But it does point towards something that I am interested in, something I call “entangled photography” or “relational photography” – what I mean by this is thinking about photography beyond photographs. What happens if we start thinking about the practice of photography as embodying the critical moment in the work? In other words, what if the “fact” of photographing something is the essential critical point of a work? I started thinking about this a while ago when I was photographing secret military bases and CIA prisons – for me, a crucial part of those projects is not always what the images look like so much as the politics of producing them.

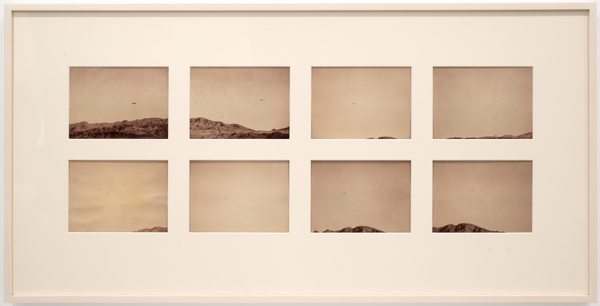

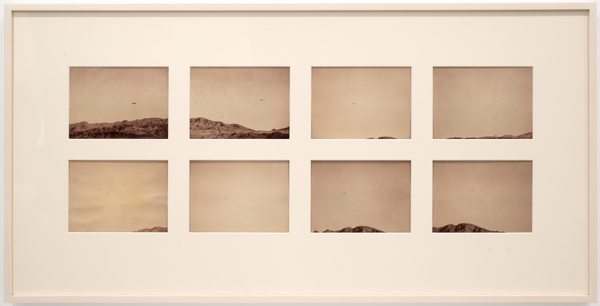

Trevor Paglen Time study (Predator; Indian Springs, NV), 2010 - Detail / Courtesy of Altman Siegel Gallery

I think I’m going to revise what I said about these relationships of seeing not being interesting to me. They are. But I think they’re part of what we might call the spatio-ethical dimension of the images’ conditions of production, rather than the aesthetic part of them. Sometimes the “entangledness” of the photograph can arise from these complex relations of seeing and counter-seeing in my work (i.e. photographing spy satellites or Predator drones photographing me), but not always. Sometimes the relational dimension can arise from the very fact of taking a photograph of something that, for political purposes, “isn’t there.” Or any number of things. But, yes, the “relational” aspects of my work are absolutely crucial, even though they’re often not self-evident in the prints themselves.

Trevor Paglen Time study (Predator; Indian Springs, NV), 2010 / Courtesy of Altman Siegel Gallery

SC: It’s intriguing to consider the fact of photographing being the critical crux of the work. However, I think I am still unclear exactly what you mean by entangled or relational photography in this context. Can you provide me with a little more insight? Are you saying that the fact that you are able to produce the photograph supersedes the photograph itself? If so, why show the photograph at all — does it then become about exhibiting proof of the action?

TP: With regard to your question about whether “that the fact that you are able to produce the photograph supersedes the photograph itself,” what I mean is a little more subtle. The “fact” of being able to produce the photograph is just one aspect of this. Let’s think about what photography is in two ways: we have one aspect of “photography” that happens prior to the photograph itself, and we have another aspect which is the photograph or image itself. In the former sense, I’m talking about all sorts of things – on one hand, you have a technological and social history of “seeing with machines” (my definition of photography). You also have specific sets of relations that “set the stage,” as it were, before you open the shutter. In every instance, those relations are going to be different, but what I mean by “entangled” photography has to do with making those relations somehow part of the work – whether visible in the final photograph or not. And yes, the photograph in a sense does become “proof” of the action, or, more precisely, the photograph may point towards the action. But that doesn’t mean that the “relational” or “entangled” aspects of the photograph supersede the photograph itself. On the contrary, we also have the photograph itself. The image or photograph is an opportunity, related yet distinct from the “relational” aspects of the photography process, to convey other sorts of meaning, metaphor, allegory, or, if you’re so inclined (I tend not to be), documentation. So I’m not really talking about either part of the photography process superseding the other, I’m talking about the fact that there are all sorts of opportunities to develop the “relational” side of the work that can contribute to what the overall artwork is.

Trevor Paglen Untitled (Predators; Indian Springs, NV), 2010 - Detail / Courtesy of Altman Siegel Gallery

SC: As you often turn to the sky to track objects such as satellites, planes and drones, you seem to present these objects engulfed in a sea of space. Formally this presents a vastness that seems to echo the sublime. I feel like this gesture is also referential of moments in art history, but I also suspect that the idea of vastness itself operates as a metaphor for the unknown, or at least that which is present but rarely detected. What are your thoughts on the concept of vastness and the sublime as it relates to some of the images on view now at Altman Siegel Gallery?

TP: This notion of the “sublime” is a really important part of what I do. I think about the sublime in relation to Jean Luc Nancy’s definition of it, which has to do with the sublime being the “sensibility of the fading of the sensible.” In other words, the sublime arises from those moments where we can sense that we cannot sense let alone understand something. This brings us to the “aesthetic” dimension of the work. In terms of contemporary critical theory, an investigation or discussion of the aesthetic is often thought of as a philosophical dead-end, a discussion that ended quite some time ago (except in reactionary ‘neo-art-for-art’s-sake’ conversations which usually function as little more than apologies for vapid art). But I’m not willing to cede aesthetics to the more reactionary corners of the art world. Historically, aesthetics has often been linked to notions of freedom: ambiguity and the sublime can be quite powerful and is something visual art can be quite good at dealing with. So it’s important to me that it’s a part of my work, but the underlying “relational” and ethical aspects of the work are crucially important. Without them, it’s just pretty pictures. And there’s no reason to care about pretty pictures.

Trevor Paglen PAN (Unknown; USA-207), 2010 / Courtesy of Altman Siegel Gallery

SC: Well, I appreciate that you are able to balance both political and aesthetic concerns without either seeming arbitrary. Taking a different turn, I’m also interested in the intersection of vision, geography and time in this new work as it applies to the 21st century. As an artist and scientist that produces artwork and research in this area, I am curious what you feel is happening right now? What are the implications of new technology and how do you feel it is changing the way we, as a collective society, view ourselves and the world around us?

TP: Ha! That question is too big for this interview, I think. This is really something I’m trying to think through. I’m not someone who thinks there’s something historically new about the fact that human perception is being radically reconfigured at the moment (I think that those in the 19th Century were probably greater, and this is a big hint to looking at some of my newer works), but at the same time, I’m interested in the ways that what “seeing” is, is historically specific. I’m extremely interested in what seeing is, and what seeing means in the contemporary moment. Of course, this has everything to do with machines, which in turn has everything to do with time (in several senses: 1) the ways in which machines rationalize time; 2) the ever-increasing “speed” of vision – think Predator drones in Pakistan flown by pilots in Nevada), which of course has everything to do with space (what Marx called the “annihilation of space with time” – again, think Predator drones flown from Nevada creating a relationally contiguous geography even though they’re obviously on opposite sides of the world). You can see the question gets really big really quickly.

Trevor Paglen: Unhuman Installation View / Courtesy of Altman Siegel Gallery

SC: Thanks for entertaining a question of that magnitude. I know that you currently have an exhibition on view, but I’d love to hear more about the research that you are currently engaged in. What are you working on now, and what projects or exhibitions do you have on the horizon?

TP: In the immediate future, I’m continuing my work on drones and continuing my work on “invisible” infrastructures that the piece The Fence (Lake Kickapoo, Texas) points to. I’ve also begun work on a longer-term project dealing with time and universality. I know that’s pretty vague, but it’s going to be a while before I begin to understand that project.

Unhuman will be on view at Altman Siegal Gallery in San Francisco through April 2, 2011.