Knots Landing: Lynda Benglis at the New Museum

More Failure More!!! -This week’s series on Failure falls in line with our previous rounds on Myth, Utopia and Rebellion. Stay tuned as we attempt to succeed this week with 6 more articles on Failure…

FORCE OF FAILURE: DailyServing’s latest week-long series

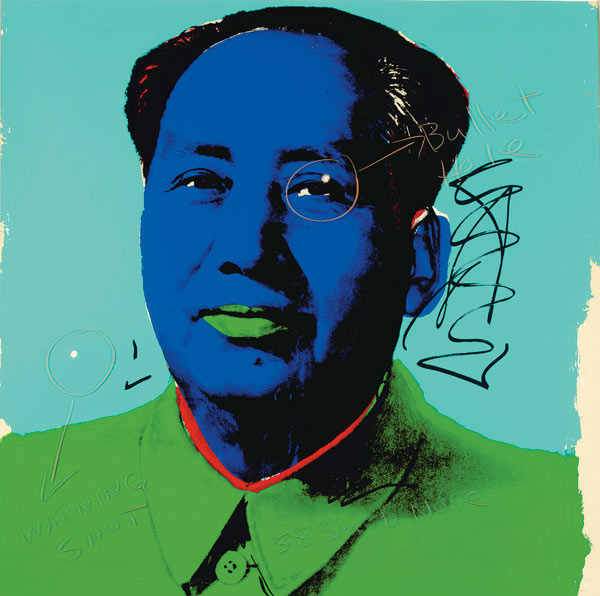

Lynda Benglis is a fearless artist. She added a much-needed sense of humor to first-generation feminism and imbued late 1960s/early ‘70s Post-Minimal sculpture with an even more needed sense of color. But a lot of her work is kind of awful. Her legendary status as an artist who went toe-to-toe with the biggest male egos in the New York art world is well deserved, and I’ll take her slumping blobs of polyurethane as examples of entropy in sculpture over Robert Smithson’s lame mirrors stuck in dirt any day. The nearly uniform praise for her current retrospective at the New Museum, however, feels like it’s based more on her historical status than on the work itself.

The Fallen Paintings (Benglis’ signature poured latex floor pieces) are by far the best in show. Slabs of poured paint yield to gravity as they diffuse Minimalism’s rigid structure with Colorfield’s floating orbs and Jackson Pollock’s subconscious process. These works call to mind a sophisticated sense of order, like Merce Cunningham’s low center of gravity choreography. However, the chicken wire, glitter, paint and plaster construction of the wall pieces, which was probably shocking in the ‘70s, just seems amateurish now. They don’t extend the properties of the material to anywhere near the same degree that the floor works do. They look good in reproduction, but in person they disappoint.

As you move forward chronologically, Benglis’ work begins to reference the body in increasingly flat-footed ways and her forms get more cheesily symbolic. The Peacock Series from the late ‘70s/early ‘80s consists of vaguely vaginal decorated fans hung on the wall. Chiron, from 2009, is a big glowing pink egg. Even Phantom, five dramatic glow-in-the-dark dripping mountains (shown here for the first time since 1971) give off a distinct Led Zeppelin “Houses of the Holy” vibe. They’re cool in a geeky sort of way, but by the time I got to Primary Structures, (Paula’s Props), a room-sized installation of blue velvet drapes, some fake trees and Greek columns, I began to question Benglis’ taste for real.

Lynda Benglis, Installation View of Primary Structures, (Paula’s Props), New Museum, 2011. Photo by Benoit Pailley.

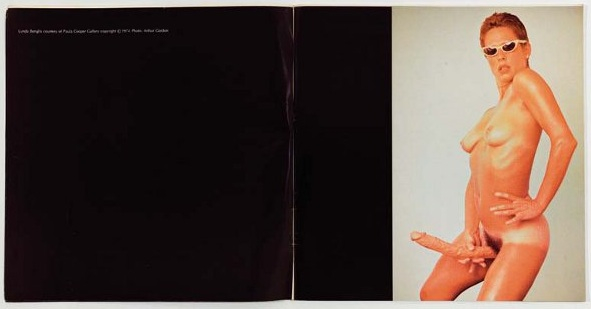

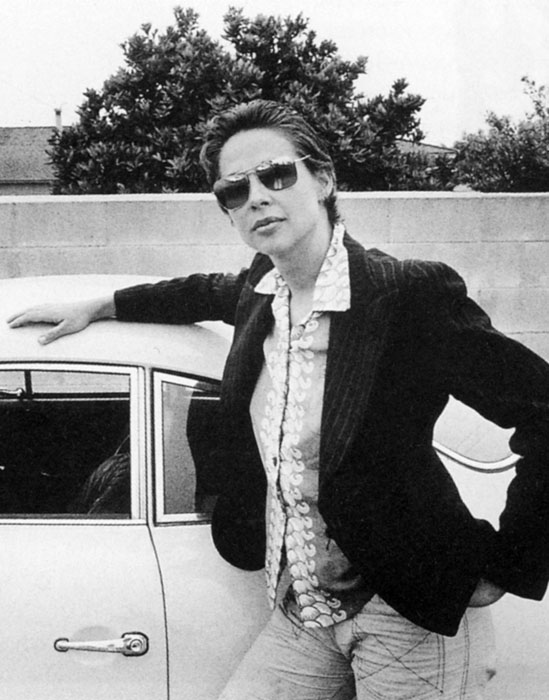

Where she completely kicks ass, however, is in her randy sense of iconic self-promotion. The photos of her at work on her floor pieces are classics, and the notorious advertisement from the November 1974 issue of Artforum, where she appears nude with slicked back hair holding a dildo between her legs, is still shockingly strong. Even though it’s been written about ad nauseum and reproduced a zillion times, it still packs a punch in person. Shot from below, Benglis appears as monumental as Michelangelo’s David and her image turns about 2,000 years of male-dominated Western Art History on its head. Set against a stark black rectangle, it’s as if Benglis is literally turning the page on Minimalism’s colorless form and gender hierarchy in the most in-your-face way possible. So what if feminists at the time hated it—Benglis was likely the first female artist to consciously construct a heroic artistic persona, and that took bigger balls than just throwing a vaginal reference or two into her work.

If many of her wall sculptures don’t quite live up to her outsized rep, there are videos and Polaroids on display that certainly do. The Amazing Bow-Wow, 1976, is an uncannily watchable short film about a hermaphroditic human-sized dog that enters into a fateful love triangle full of jealousy and lust. It’s as unflinchingly gutsy as any Paul McCarthy, but with way more heart. Displayed next to the video is a series of Polaroids called Secrets that combine pornish images of Benglis and Robert Morris with close-ups of flowers. Here, the collusion between nature, sex and overlapping bodies is as palpable as it is in the floor sculptures. Rarely exhibited, the photos’ old wooden frames have the vibe of pre-boutique-era SoHo. Nostalgic art relic nerds, get ready.

All of Benglis’ work might not stand the test of time. She’s like a classic rock band that put out three or four great albums with timeless cover art. Like a lot of those bands, Benglis synthed out in the ‘80s and never quite recovered, but it doesn’t matter. The lesson here is that she full-on embraced failure in her work, through both an entropic use of materials and by taking risks that few artists today would even consider. For all of her posturing and dildo-ing around, she still feels human and extremely relatable, and she’s more than paid her dues. Every New Yorker knows that she’s one of ours, so if she makes criminally bad art, it’s cool. We just look the other way.